Why do some big critters die young, while others stay small and live longer? Now, Stanford Medicine researchers may have stumbled on clues to answer that question, but the details, said Daniel Jarosz, PhD, are not necessarily found in a creature's DNA.

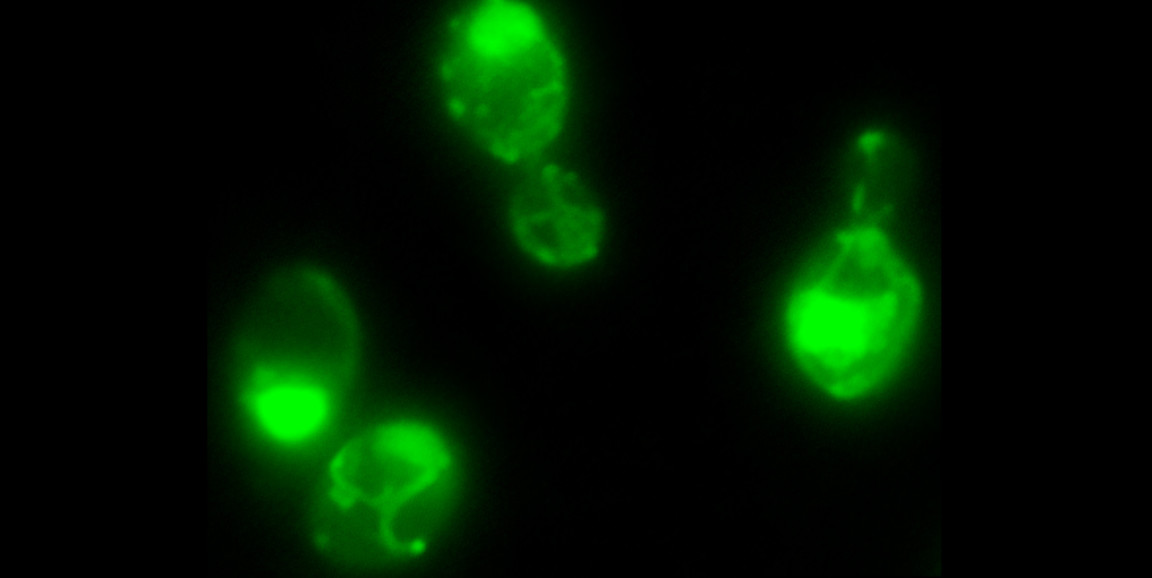

Instead, in a paper published Sept. 21 in eLife, Jarosz and a team of researchers show that prions -- proteins that fold in on themselves to form infectious aggregates -- can serve as a switch of sorts, triggering yeast cells to grow big and die early.

What's more, the affected cell's descendants continue to carry the trait. "We found this element -- a prion -- that can control that switch: whether yeast cells and their progeny grow to be really big, or not," said Jarosz, an associate professor of chemical and systems biology and of developmental biology, who led the study.

And this all happens without changing the cell's genetic code.

The discovery is part of the growing field of epigenetics, which studies how the environment and personal behaviors influence the way genes are expressed, without changing the genes themselves.

In this case, the research team wasn't looking to use their results to change the life trajectories of humans. Not only would that be unethical but it would also take an entire human lifespan for results to play out, Jarosz explained.

Instead, they introduced prions into the cells of fast-growing baker's yeast to affect the developing proteins inside.

Trade offs

Jarosz's lab has been studying epigenetics and the influence of prions in yeast cells -- a fast-growing, easily manipulated group of cells -- for the past eight years.

In their latest research, the team saw that yeast cells with a specific prion inserted into them reproduced for an average of 23 generations, while unmodified yeast cells reproduced for 30 generations. Yet sizewise, cells with the prion were about 23% larger than the unmodified yeast cells, according to the study. They also grew much faster.

Another important finding from the research, Jarosz said, was that the protein changes spurred by the prion remained present in that cell's offspring. In other words, the cells that reproduced from the prion-infected cell contained the same protein changes as those caused by the prion without being infected by prions themselves.

The team's discovery could be used to influence growth and expression in cells of a variety of human diseases, including cancer, Jarosz said: "It's not an unreasonable supposition, given that many of these same activities can be altered in tumors."

If that turned out to be true, targeting the grow fast and die mechanism could provide new treatment pathways for cancer or possibly other diseases, according to the paper.

The results also bring up questions about whether injuries or traumatic events can influence the body and change the physical, rather than genetic, nature of cells in ways that influence future behavior, or even future generations, Jarosz said.

"The question is, 'Can such events leave some enduring trace in the body that is more than a scar -- something that could serve as a physical memory of sorts?'" Jarosz said. Such a phenomenon could allow cells or organisms to adaptively alter their future behavior based on past experiences.

That research on yeast cells, which Jarosz called a well-studied workhorse of biology, could continue producing new discoveries is awe-inspiring to him.

"We work on many different organisms," Jarosz said. "Yet I find it really crazy and very humbling to realize that, even in this simple and widely used model organism, where cell size and proliferation have been studied extensively, no one saw this before because they didn't know to look for it."

Photo by Daniel Jarosz