The late Stanford Medicine neuroscientist Ben Barres, MD, PhD, was among the first to grasp the immense significance of an overlooked majority of cells in the brain that aren't neurons, collectively called glia.

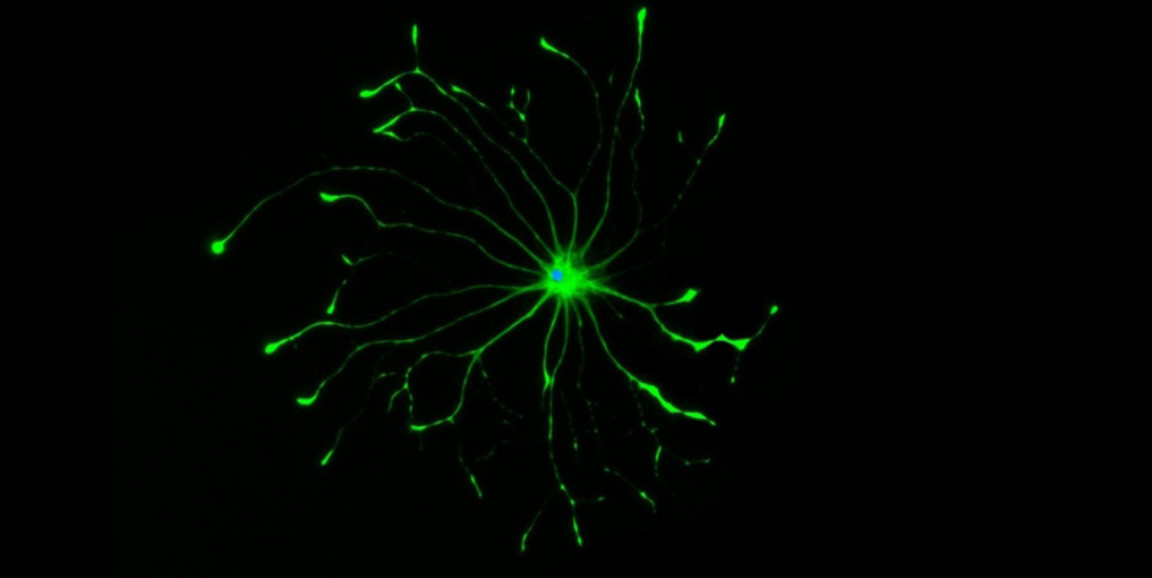

Barres' experiments over the years revealed that star-shaped glial cells, called astrocytes, act like angels, giving neurons what they need when they need it. Unsung yet ubiquitous, astrocytes amount to 20% to 30% of all the cells in the brain. They promote neurons' survival and health by gobbling up debris cluttering a cell's external environment; supplying nutrients; and midwifing the birth and removal of new and old neuronal connections, among many other things.

But under certain inflammatory conditions in the brain, Barres' team showed, astrocytes take on a demonic edge. In a study published in Nature in January 2017 and in subsequent studies, the researchers reported that these so-called "reactive astrocytes" go haywire and kill injured nerve cells that might otherwise have repaired themselves and survived. (The reactive astrocytes spare uninjured neurons.)

The January 2017 study included experiments designed to better understand why some astrocytes were turning against neurons. The results of these experiments pointed to an unknown toxic substance the aberrant astrocytes secreted. When I interviewed Barres for a news release I was writing about this study, he told me this was the most important work ever to emerge from his decades of research on glia. Still, the question of how rogue astrocytes execute their dastardly designs remained open.

Four years after his death, possibly the greatest mystery Barres ever sought to solve has become a bit less opaque. Researchers from his former lab, who still carry the glial torch, have fingered a particular type of substance whose excess, propelled by astrocytes' Jekyll-to-Hyde shift, is lethal to damaged neurons.

Passing the torch

By the time his January 2017 paper was published, Barres had been diagnosed with terminal pancreatic cancer and knew he was going to die before too long. He also knew that finding out how astrocytes-gone-wrong go about killing damaged neurons could be a crucial step toward slowing -- or even stopping -- disease progression in a number of neurodegenerative disorders, such as Lou Gehrig's, Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and Huntington's diseases. He told me his greatest regret was that he wouldn't live long enough to see this prospect come to fruition.

Nobody knows what's in it for astrocytes that go over to the dark side, or for the brain they supposedly serve. But, said Kevin Guttenplan, PhD, a former Barres grad student, "figuring out how they do it might help us guess why they do it."

When Barres died in December 2017, the character of the crucial toxic substance, or substances, released by reactive astrocytes to kill injured but salvageable neurons remained unknown. But Barres had determinedly nailed down financial support and good landing places for his postdoc and grad student trainees. He designated Guttenplan to find the elusive neurotoxic factor. Guttenplan forged ahead under the tutelage of former Barres-lab postdoc Shane Liddelow, PhD, who has since become an assistant professor of neuroscience and physiology at New York University.

Now, a solution to the poison puzzle has been published in Nature. Guttenplan, currently a postdoc at Oregon Health Science University, is the lead author; Liddelow shares senior authorship with Barres.

Lethal lipids

"Initially, everybody assumed the mystery toxin was probably a protein," said Guttenplan. Most of the time in biology, whatever it is you're looking for turns out to be a protein.

One protein of particular interest, because it popped up in just the right place in a critical experiment, was ApoE, a shuttlebus for lipids, (a scientific term for fatty substances). One of ApoE's three major variants, called ApoE4, is infamous for promoting the development of Alzheimer's, although no one has a clue how it does this.

But the long-sought toxic factor turned out to be not ApoE, but the lipids it was gripping -- specifically, unusually elongated varieties (the longer the deadlier) of certain saturated fatty acids and their chemical relatives, phosphatidylcholines. These substances are ordinarily produced at exceedingly low levels. But in reactive astrocytes their production jumps up, leading to a greater manifestation of these lengthy lipids in association with ApoE.

Liddelow is in active pursuit of a drug capable of blocking the sole enzyme that's essential to producing the extra-long lipids. "There's not a single blocker available now to stop that crucial lipid-elongating enzyme," he said.

ApoE's three different versions may each carry different mixes and amounts of the offending lipid passengers. Liddelow's team hopes to find out if this could account for the three versions' differential Alzheimer's-risk-factor status.

"This was our homage to Ben," Liddelow said. "We knew this was the last paper that would ever bear his name. This was 30 years of his career culminating in this paper."

Somewhere, Barres is smiling.

Photo by Shane Liddelow