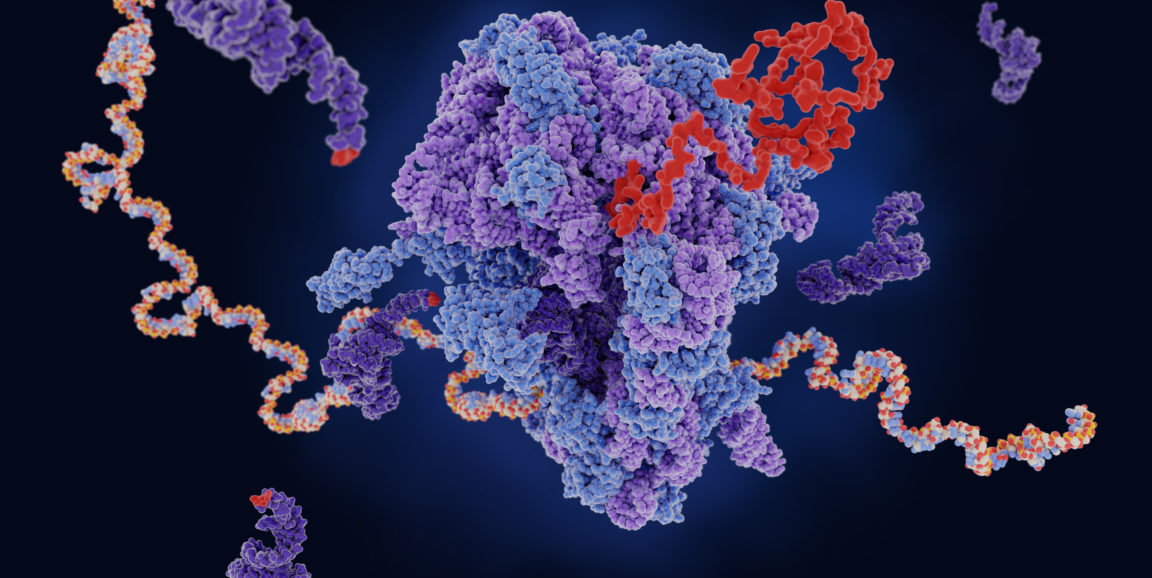

Everyday our cells churn out proteins that perform crucial functions in our bodies. Some protect us from disease. Others help us move. Proteins are involved in just about every bodily task.

But sometimes our cells make mistakes, creating proteins that are too long, too short or the wrong shape.

Not only are these wayward proteins sometimes unable to complete their assigned tasks, they can also aggregate into clumps that make it hard for other cells and molecules to do their jobs.

In a study published recently in Nature, Stanford Medicine researchers found that the function of ribosomes -- the cellular machines that make proteins -- degrades with age, pointing to a potential link between the decline of ribosome health and such age-related diseases as Parkinson's and Alzheimer's, which are characterized by these clumps of dysfunctional proteins.

For their study, the scientists examined yeast and roundworms, two organisms commonly used in experiments to mimic human aging. Their goal, as explained in an article published by the Stanford University News Service, was "getting down to the basic biology of these diseases and understanding what mechanisms cause them," said Kevin Stein, lead author of the paper and a former postdoctoral scholar in the lab of Judith Frydman, PhD, professor of biology and of genetics. Their hope is that future therapies can be more precisely targeted at the disease mechanisms as opposed to "trial and error."

Folding flubs

The scientists found that as the organisms aged, ribosomes, which use genetic material to create proteins, start to slow down and crash into each other like rogue bumper cars. The more the ribosomes malfunctioned, the more "misfolded" proteins the researchers found. (During protein formation, the near-final protein folds into a specific three-dimensional shape that helps it carry out its function.)

But it's not just the elderly ribosomes that are responsible. Even in younger organisms, ribosomes sometimes act up and make the occasional misfolded protein, albeit less frequently than their aged counterparts. Our cells have a quality-control mechanism to identify and remove those misfolded proteins before they create disease-causing clogs in the cellular assembly line.

Unfortunately, even a small increase in the number of misfolded proteins can overwhelm this system. The researchers found that even if the older ribosomes only pumped out 10% more dysfunctional proteins than fresher ribosomes, that was enough to allow the damaged proteins time to aggregate and form disease-causing clumps that the cells could no longer easily clear.

"Every cell normally makes millions of these newly translated proteins," said Frydman, senior author of the study and the Donald Kennedy Chair in the School of Humanities and Sciences. That means that even a tiny increase in the frequency of errors can have a huge effect.

The biggest question though, remains to be solved: Why does aging lead to ribosomal malfunctioning to begin with? And can it be stopped? Some genetic research suggests that certain mutations could lengthen the healthy lifespan of ribosomes in yeast. It's possible that targeting these genes could have similarly positive impacts in humans.

"This is only the beginning of a very fascinating future," said Fabián Morales-Polanco, a co-author of the research and a postdoctoral scholar in the Frydman lab. "We set a precedent for something new, and there are millions of questions -- and probably hundreds of papers -- that will follow."

Photo by Juan Gärtner