As the COVID-19 pandemic hit and vaccine development went into hyperdrive, Joseph DeSimone, an expert in precision drug delivery and 3D printing technology, had an idea for a new research project: a 3D-printed vaccine patch.

DeSimone, PhD, professor of radiology and of chemical engineering, knew that the dermal layer of the skin harbors many more immune cells than the muscle, and is therefore an ideal vaccine target. For some time, he had also been working on 3D-printed microneedle patches to deliver substances to the skin. Molded microneedle patches are already mainstream in the cosmetics industry, used as a vehicle for skin treatment, DeSimone said, but 3D printed patches offer the possibility of better, more precise designs.

After about 18 months of development, DeSimone's group published a paper detailing their vaccine patch prototype, demonstrating that the concept was not only feasible but also potentially more effective than injected vaccinations at generating a robust immune response.

I spoke with DeSimone about the development of the patch, which was recently recognized as one of Fast Company's 2022 World Changing Ideas, and asked him to describe how the vaccine patch works, whether it might impact progress toward broad acceptance of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, the challenges of developing the patch for widespread use, and what the future may hold for 3D-printed microneedle patches.

How do you make the vaccine patch and how does it work?

My lab has developed 3D printers that are up to 50-times more precise than commercial printers used for making things like running shoes and football helmets.

Using these printers, we are making precisely printed microneedle patches into a vaccine delivery vehicle.

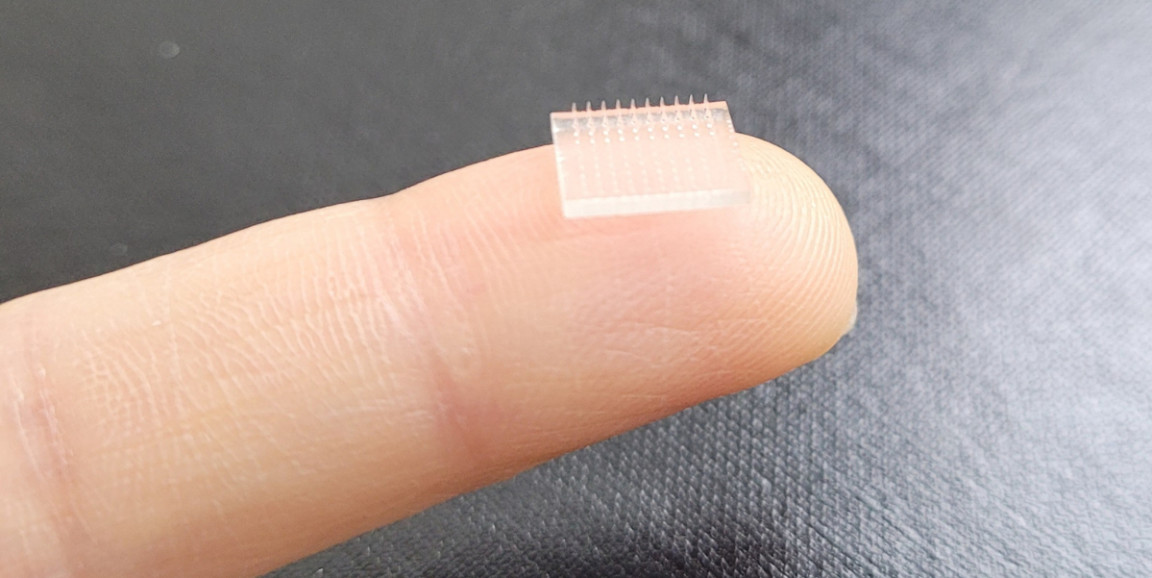

The patches are about a 1-by-1-centimeter square with a 10-by-10 grid of microneedles. And because they are 3D printed rather than molded, we can do some interesting things to improve how they work. For example, we increase the surface area of the needles by printing faceted rather than smooth needles -- meaning they're shaped almost like thin Christmas trees. Also, when the needles are all the same height, it takes a lot of force to press the patch into the skin, an issue we call the bed-of-nails problem. To address that, we make the microneedles in varying heights.

We then dip the needles into a vaccine that's in the form of a sugar solution, and dry away the water so what's left is almost like a sugar coating on a glazed doughnut. When we compared the immune response the patch generates in mice with the immune response from needle delivery, we found a 50-times stronger response when delivering the same vaccine and the same amount of vaccine to the skin rather than the muscle.

Are you developing a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine patch?

In partnership with Peter Kim, PhD, professor of biochemistry at Stanford, we've recently tested a SARS-CoV-2 protein-based vaccine patch in mice, and we're also starting to test mRNA vaccines via patch. By the end of this year, I hope we'll finalize the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine formulation.

What are the advantages of a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine patch, compared to an intramuscular injection?

There are 100 to 1,000 times more migratory immune cells in the dermis of the skin than in the muscle. And although the standard practice of injecting the Moderna or Pfizer vaccines for SARS-CoV-2 into someone's arm muscle is efficient and reliable, those shots go right through the skin and miss most of the immune cells that live there. The vaccine patch enables much more precise delivery to those cells.

Patches are also easy to self-administer, freeing up hundreds of thousands of health care workers to do things other than give vaccines. Finally, the patch is pain free. Some level of vaccine hesitancy involves fear of needles, and I think a patch can address that concern.

Are there any barriers to widespread use of a vaccine patch?

One of the biggest challenges is delivering a reliable, repeatable dosage. Using a syringe to deliver a liquid vaccine into someone's arm is straightforward and, in medicine, you need that kind of reliability. With microneedles, because one can apply different levels of force and pressures to the patch, some of the vaccine coating can get sloughed off as it's being inserted into the skin, like sugar falling off a doughnut, which would reduce its effectiveness.

To deal with that problem, we're developing some amazing new microneedle designs. With our 3D printers, we hope to create microneedles that are cage-like pyramidal structures that can protect the vaccine cargo (what's meant to be delivered to the skin) on the inside. We're also adding mechanical properties that turn the structures into minipumps. No one's ever made things like this before. These designs could make microneedles a robust and reliable method of drug or vaccine delivery.

Photo courtesy of Joseph DeSimone