A tiny marine creature with a strange lifestyle may provide valuable insights into human neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease, according to scientists at Stanford Medicine.

Botryllus schlosseri, also called a star tunicate, is humans' closest evolutionary relative among invertebrates in the sea. Attached to rocks along the coast, it appears as a tiny flower-shaped organism. Star tunicates start life as little tadpole-like creatures with two brains, swimming in the ocean. But eventually they drift down from the surface, settling into a stationary life on a rock, joining a colony of other tunicates.

As the tunicate, also known as a sea squirt, adapts to its new couch-potato lifestyle, it loses brain power: One of the two brains, its use for sea navigation now obsolete, begins to dissolve. The way the invertebrate's brain degenerates and disappears has important parallels to the way the brain degenerates in human neural disorders, said Irving Weissman, MD, director of the Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine.

In a paper published July 11 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Weissman and his colleagues showed that many of the genes associated with neurodegeneration in Botryllus have analogues to the genes associated with neurodegeneration in humans. What's more, the researchers said, genetic changes that build up over decades in the Botryllus colonies affect neurodegeneration in many of the same ways as age-related genetic changes affect neurodegeneration in older people.

Weissman and other scientists think that Botryllus is the modern-day representative of the beginning of the vertebrate branch of the tree of life. Every animal with a backbone, they think, evolved first from this tiny sea tunicate.

"Although the path that led to humans split far back in time, the essential stuff might stay the same," said Weissman, who is the Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Professor in Clinical Investigation in Cancer Research, and is the co-senior author on the paper with scientist Ayelet Voskoboynik, PhD, who is leading studies on this marine organism at Stanford's Hopkins Marine Station in Pacific Grove. Postdoctoral scholar Chiara Anselmi, PhD, is first author on the paper.

Drawing parallels

The life cycle of Botryllus offers a lot of advantages as a model organism for studies of neurodegeneration: Every week, each Botryllus organisms in a colony reproduces asexually, producing two to four buds that become new organisms. Each bud completes its development within two weeks, lives as an adult for one week, and then deteriorates and dies on the last day of the third week.

The researchers originally thought the number of Botryllus' neurons would remain stable during most of the final week of its adult stage, Anselmi said. But that's not what they saw. "There is a specific pattern of neural degeneration," she said. "Out of about 1,000 genes that are involved in neural degeneration, we found that 428 are genes shared by humans and Botryllus."

In addition to their speedy lifecycle, Botryllus offers another advantage as a research model -- it seems to accumulate mutations in its genes similarly to humans. The Botryllus colonies in this study have been around for more than 20 years. Because the organisms in the colony reproduce asexually through a stem cell-mediated process, their stem cells are the only cells in the colonies that are maintained throughout the years, and they most likely accumulate defects over time in the same way human genes do.

Older stem cells, smaller brains

Older people develop neurodegenerative disease more often than young people, and human neural stem cells are less active when they're older, compared to when young. A similar pattern is seen in aged Botryllus colonies.

"Something happens to the stem cells in the colony along the way and, after 20 years, they can't regenerate the way they did when they were young," Voskoboynik said. "There is a reduction in neurons of almost 30% in individual brains in the aged colony and, even at the peak of neural development, the older colonies can't match the neural generation of young colonies. It is amazing that in an invertebrate you can see the same changes in genes from young to old that you see in aging humans."

Furthermore, the tunicates in the aging colonies share a molecular likeness with people who have Alzheimer's disease, the neurodegenerative disease that usually strikes in the last decades of life, said Voskoboynik. One of the hallmarks of Alzheimer's is an accumulation of amyloid plaques, which are created when amyloid precursor proteins (APP) glom together. "When individuals in the aged colonies go through that asexual cycle, not only do they make far fewer neurons, but those neurons have a lot of APP," Weissman said.

Because no one knows the cause of Alzheimer's disease or the significance of amyloid plaques in the neurons, the researchers are hopeful that Botryllus might be a powerful platform for studying the disease.

"We can easily create 250 offspring every week and study various aspects of their neural development and degeneration. For instance, we can block specific pathways that might lead to amyloid accumulation or other aspects of Alzheimer's neurodegeneration," said Weissman.

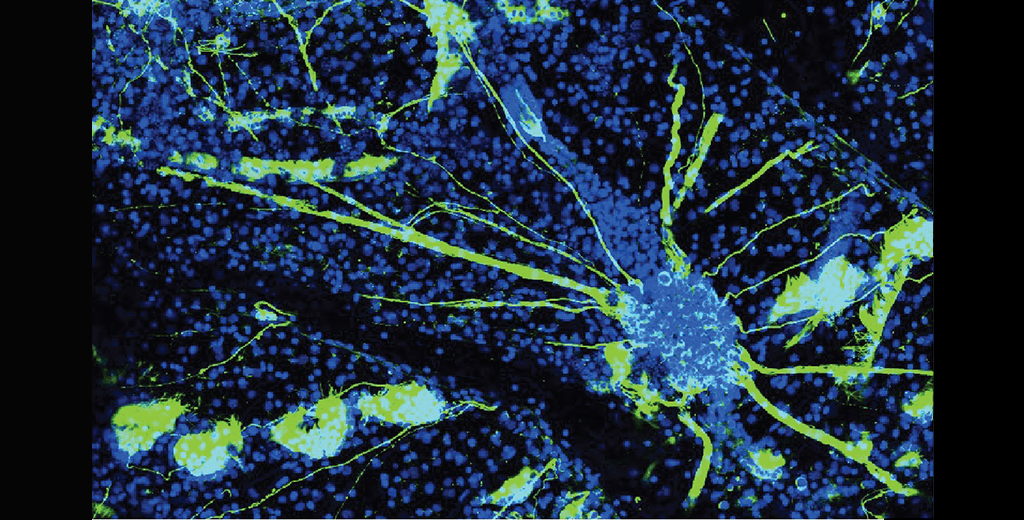

Top photo, depicting the nervous system of Botryllus Schlosseri, courtesy of Chiara Anselmi

This article was originally published by the Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine