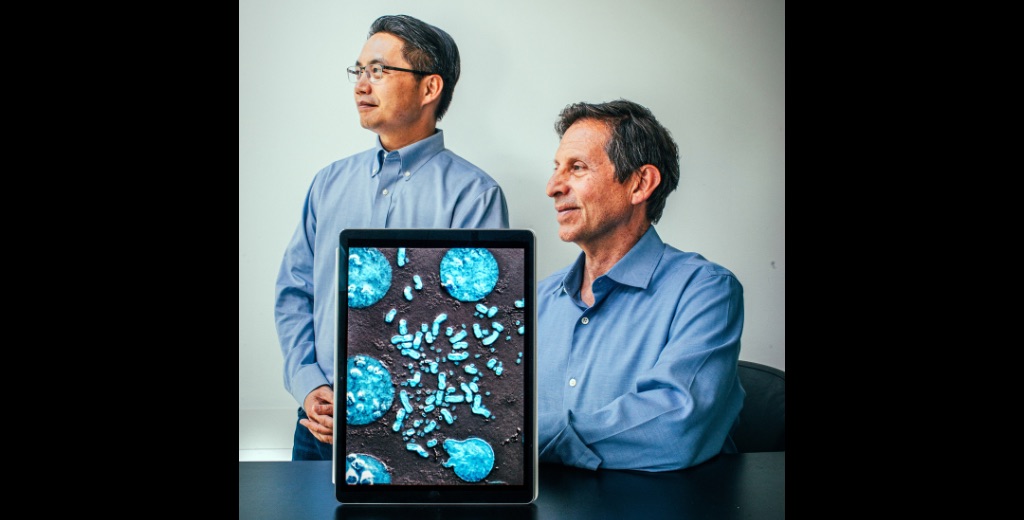

Every once in a while a story just seems to write itself. That's what happened when I was working on my feature story about vicious DNA circles for the latest issue of Stanford Medicine magazine. Fellow writers will appreciate it when I say that the scientists, Paul Mischel, MD, and Howard Chang, MD, PhD, were quote machines. Their enthusiasm and mutual respect -- born of a chance meeting at a Stanford seminar -- was palpable from our earliest conversations. They made my job (relatively) easy.

The article, titled "Vicious Circles," describes how tiny DNA circles -- previously thought to be merely roly-poly detritus -- cooperate to vastly amp up the production of cancer-associated proteins and worsen disease prognosis.

They do so by clumping together in rafts in the nucleus, allowing the promiscuous stimulation of gene expression across multiple circles. This is very unlike the ways that genes are expressed on the stately chromosomes near which the circles romp. It's a fascinating finding that upends some formerly untouchable truths in the field of genetics.

It also gave me ample opportunity to trot out a seemingly endless number of circle-focused puns and analogies. (As my eye-rolling editors can attest, I dove hard into the concept that it's better to ask for forgiveness than permission.)

But there was one fact I couldn't manage to fully wedge into the story. During our conversation, Mischel made an elegant comparison: Our former understanding of genetics as a realm in which the most important players live primarily on chromosomes is akin to the ancient astronomer and mathematician Ptolemy's Earth-centric map of the universe. It's not accurate, but enough details were right that the map stood until the 16th century, when Copernicus rightly proposed that the planets instead orbit around the Sun.

"People are visual learners," Mischel says in the article. "But the molecular world is too small for us to see. So we make maps to help us understand. In cancer genetics, the map has been centered on the role of chromosomes. But our new findings have upended this map. Now we are redrawing our map and recharting our course to help patients with the most aggressive forms of cancer."

Space constraints meant I wasn't able to include Ptolemy's misstep in my article. But I wish I had. Because, after all, what is an orbit but a kind of smushed up circle? Opportunity lost!

So if you're interested in reading about how SpaghettiOs, Ring around the Rosie and bubbles in a bathtub relate to the next generation of cancer care, check it out. I'll just be over here twiddling my thumbs. In circles.

Photo by Timothy Archibald