Doctors don't normally possess the ability to all-powerfully dictate medical outcomes. But when professor of medicine Abraham Verghese, MD, writes his novels, he finds it within the realm of possibility.

On May 2, his novel The Covenant of Water was released. It's a 736-page tome that was published 14 years after his New York Times bestseller Cutting for Stone.

The Covenant of Water, which was recently chosen for Oprah's Book Club and has received rave reviews, including from The Washington Post and The New York Times, tracks three generations of a family living in Kerala, a state on the southern tip of India. They're plagued by a mysterious plight: At least one person from each generation drowns, plot devices used as the families grieve their losses. His characters also suffer from leprosy, opium addiction, smallpox and birth defects, among other conditions.

The point of the book, according to Verghese, is to share the magic of life's major themes -- love and faith -- although medicine is a conduit to explore these themes.

As a doctor and teacher of medical students, Verghese emphasizes the human side of medicine, advocating for an empathetic bedside manner with patients. This approach, he said, draws him to develop characters and understand the human condition, a key ingredient in good fiction writing.

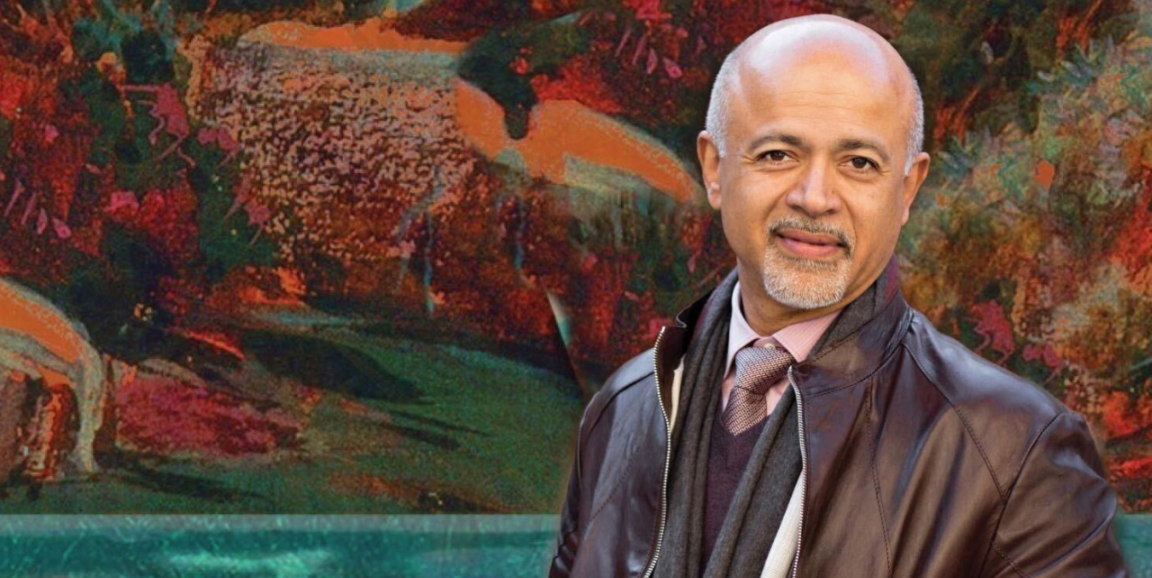

Verghese, the Linda R. Meier and Joan F. Lane Provostial Professor of medicine, spoke about the connection between writing, medicine and fiction.

Doctors, if they write, often gravitate toward nonfiction. What inspired you to write fiction?

Fiction is the great lie that tells the truth. Fiction has a major influence over how we live our lives. In 1852, Uncle Tom's Cabin took the country by storm and helped end slavery in this country. And in England, a 1937 book called The Citadel is thought to have contributed to the genesis of the National Health Service because of its depiction of undesirable conditions in a mining town.

Fiction can be transformative and powerful. When fiction resonates with us, it's because it speaks to some truth in our own lives, something we can carry with us. It puzzles me that we educate our children from the earliest moments of life with fairy tales but then the moment we come of age, we tend to drift away from the very thing that made us who we are. With my novels, I return to my creative roots.

How does fiction writing compare with practicing medicine?

Fiction is liberating for me. That's how I first got into it: I was an infectious disease physician working with HIV patients in the early '80s, and what I was seeing in the hospital every day was tragic. When I came home, writing fiction was my escape. In my stories, I could keep people alive, and I could reverse the course of disease. Writing has its great challenges, like keeping readers interested, but it's a relief from the sometimes sobering reality of medicine.

How does medicine inform your writing?

People often assume that I'm wearing two different hats: I'm a doctor at certain times, and I'm a writer at other times, but I don't make a switch. The same lens that I have used for many years as a physician -- looking at patients with a great deal of curiosity and empathy -- is the same lens that I bring to writing. We physicians have some advantage as writers in that we're taught to observe and to bring separate facts together into a unifying diagnosis. Some of those elements take place in writing as well. The discipline of medicine has also helped me approach the blank page. Years of studying in medical school, residency and fellowship, prepare you for the rigor and concentration a project requires, be it a novel, a chapter in a book or a grant.

Why did you set your novel in Kerala, India, from the early 1900s to the 1970s?

When my niece was 5, she asked my mother what life in Kerala was like when she was a little girl. My mother was in her 70s. To thoroughly answer the question, she began to write a manuscript in her very elegant script and illustrated it to convey to her granddaughter what her life had been like. And when I saw that manuscript, it occurred to me what a rich setting that was for a novel. I wasn't born in Kerala -- I was born in Africa -- so even though I visited Kerala every summer and visited often during medical school, I couldn't speak about it with the same authority as someone who was born there. With my mom's help, and a tremendous amount of research, I finally felt I was ready to set this novel in Kerala, thanks to her.

That informed perspective, of intimately knowing a place, stokes my creativity, which keeps me coming back to fiction.

Photo by Jason Henry