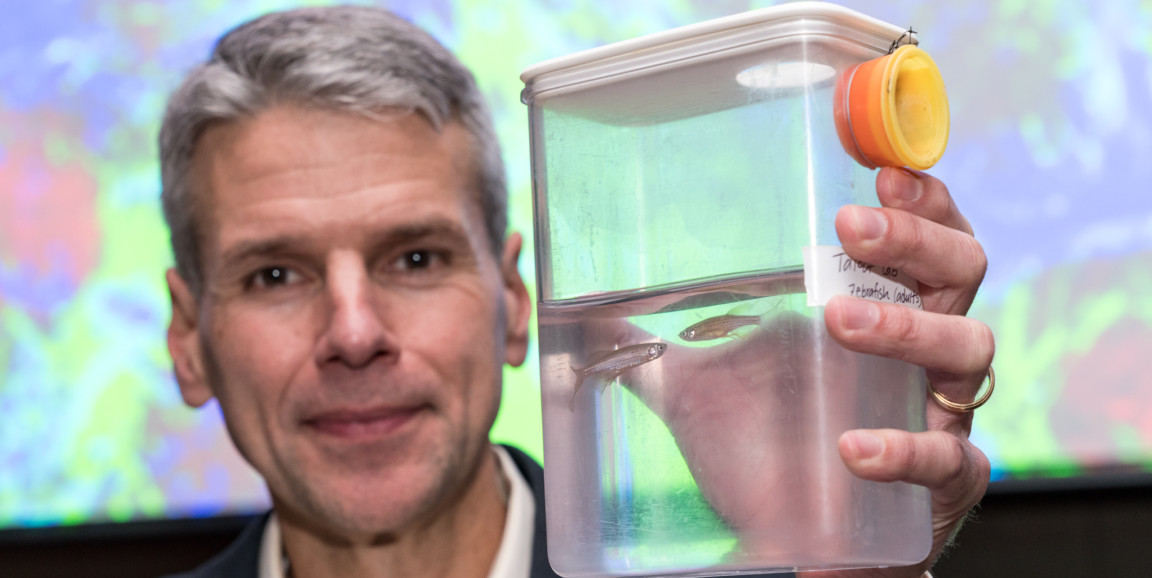

Will Talbot, PhD, knew the obvious question and decided to address it directly. "Why does the medical school employ someone who studies zebrafish?" Talbot asked the several hundred people assembled on the Stanford campus recently to celebrate the Discovery Innovation Awards, competitive seed grants that support early stage research in human biology.

A developmental biologist as well as a senior associate dean at the School of Medicine, Talbot explained that he studies the small striped creatures because, like humans, zebrafish are vertebrates that rely on myelin, a substance that is essential for a functioning nervous system. He said he can raise huge numbers of fish in his lab and peer straight into their nervous systems because the embryos and larvae are transparent.

Five years ago, Talbot said he wanted to study zebrafish that couldn't make myelin to see if he could devise a strategy to reverse the defect. If he could restart myelin production in zebrafish, he knew it could have implications for treating people with multiple sclerosis, a disabling autoimmune disease caused by damage to the myelin sheath surrounding nerve cells.

At the time, Talbot said he couldn't approach traditional funding sources for medical research -- he didn't have enough evidence to show them -- but he needed resources. "How do you pay people in the lab?" he asked. "How do you feed the fish?"

Talbot applied for a Stanford Medicine Discovery Innovation Award, funded by philanthropists who believe that one discovery can have an exponential impact on human health. A committee of experts selected Talbot's application and awarded him $95,000 to pursue a project with the mutant zebrafish.

His research revealed on molecular level why there was no myelin in the mutant fish. From there, he was able to reverse the defect. This line of research is so promising that other traditional funding organizations have pitched in.

"A few years ago," he said, "they wouldn't have even considered funding us."

The Discovery Innovation Awards, which have distributed $6 million over the last four years, come with little red tape and few constraints. These grants have resulted in 119 research papers and more than $36 million in follow-on funding, according to Stanford Medical Center Development records.

At the campus event celebrating the most recent group of awardees, Talbot joined three other scientists who won the awards in previous years to talk about their research.

Geneticist Anne Brunet, PhD, described the methods that she developed to read each cell's chromatin signature and understand the genetic mechanisms of aging and longevity. Computational biochemist Rhiju Das, PhD, discussed Eterna, an online game he created to crowdsource the design of molecular medicines. And David Schneider, PhD, talked about ways to increase resilience to infectious diseases.

Nobel Laureate Roger Kornberg, PhD, introduced the award winners and emphasized the importance of research that increases fundamental knowledge of human biology. "Science is hard and it's unpredictable," Kornberg said. "There's no guarantee of success and discoveries are by their nature accidental. They depend on luck and serendipity and they require a long time."

Kornberg was the first scientist to discover the three-dimensional structure of the enzyme that converts DNA into messenger RNA. This discovery showed how human cells -- each of which contains a person's entire genetic code -- selectively read out sections and differentiate into all the types of cells necessary to sustain life.

"I started on the work while in my 30s," he said. "When we succeeded, I was approaching 60." He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2006, six months shy of his 60th birthday.

Now, Kornberg said people often ask him what he believes are the most promising areas of research and what research should be funded.

"I answer with the obvious," he said. "We cannot predict the future. All white papers can be replaced by a simple statement: support the brightest, most ambitious, most hard-working young scientists and they will invent the future."

Photo by Paul Keitz