The medical dictionary was small, with a worn green-black cover. It was all but invisible among the bright self-helps in the tiny health section at Bell's Books, an 80-year-old independent bookshop in downtown Palo Alto.

Though the dictionary was published in 1898, the price, written lightly in pencil, was only $14 -- more than the 75 cents advertised on the title page, but a far cry from the hundreds charged for Bell's rarest books, carefully curated upstairs.

I love old books, and I found this one hard to resist. Maybe it was because the dictionary featured a wonderfully odd assortment of terms, with definitions averaging about six words, like frog-face (abnormal facial appearance due to tumors or nasal polypus) and hatters' disease (consumption from inhalation of particles of felt). Or maybe it was because both the front and back covers had been folded so hard they were creased deeply down the middle, nearly broken.

I pictured a doctor on a house call with a stethoscope in one hand and in the other, his trusty Warner's Pocket Medical Dictionary of To-Day. But really, would a practicing physician need a portable reference to define, at a patient's bedside, green sickness (an anemic disease of girls) or grocer's itch (an eczematous affection of the hands)? Or was it an amateur's version of turn-of-the-century medicine?

I shelled out my $14 and called Drew Bourn, PhD, the historical curator at the Stanford Medical History Center. Could he help me with a sort of Antiques Roadshow, medical edition?

Of course, Bourn said: "Research is one of the pleasures of life."

When I arrived at the center, he had already unearthed Stanford's pristine copy of the Warner dictionary. But that was all we had.

On WorldCat, a database of holdings for 72,000 libraries, we discovered that a Warner's dictionary graced the shelves at Columbia University, the U.S. National Library of Medicine and the University of California, Los Angeles. We also found the title of the author's other book: an 1888 tome called William R. Warner's Therapeutic Ready Reference Book for Physicians.

That got us wondering about Warner. A simple Google search revealed that he'd started a retail pharmacy in Philadelphia around 1856. That he'd devised methods to make the first sugar-coated pills in America. And that after an evolution or two, the business was acquired by drug giant Pfizer in 2000.

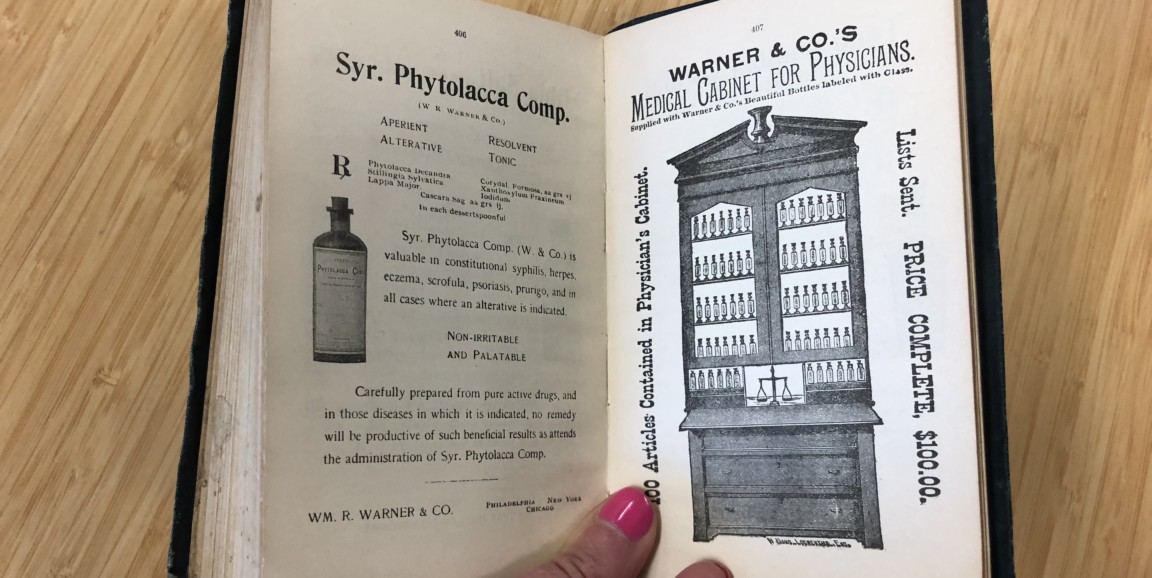

All this made sense in context of the dictionary, which contains full pages touting William R. Warner & Co.'s hypodermic syringes, medical cabinet for physicians ("supplied with Warner & Co.'s beautiful bottles labeled with glass") and "soluble and reliable pills." Maybe the book was a thinly-veiled advertisement.

I kept clicking through results and found something else interesting. Medical journals had published contemporary reviews of Warner's dictionary -- and apparently it was a legitimate job aid with terminology that reflected the times.

"This is such a distinct aid, and such a strictly modern compilation, that every physician, not already provided with a pocket dictionary of late date, should at once supply himself," gushed The Clinical Review: A Journal of Practical Medicine and Surgery circa 1900.

Though not contesting the book's accuracy, another was not so complimentary.

"Conciseness in a work of this kind is apt to be carried to the extreme, and this is the chief criticism to be made on the book under consideration," wrote a reviewer in The Medical Standard in 1897.

JAMA proclaimed Warner's work "excellent" and "very useful to students and others" in a one-liner published during a sort of golden age of medical dictionary reviews between 1890 to 1935. My favorite, in 1926, complained, "The review of a new dictionary or telephone book is rather a thankless task," before wearily continuing, "The definition of terms in the field of physical therapy are no more accurate here than in any other dictionary."

Perhaps wary of such uninspired reviewers, Warner seems to have bought space in medical journals for glowing, if unexciting, testimonials from doctors. They hailed from towns big and small, and they contributed comments that rivaled Warner's definitions in conciseness. "A very handy volume," wrote Dr. R.S. Urgler of Oakville, Washington. "I am highly pleased with it," piped up J. Chilson, MD, of Fall Brook, California.

Though I'm unsure whether Drs. Urgler and Chilson existed outside Warner's imagination, it seems likely that some doctor, somewhere found this dictionary helpful enough to crease its covers with wear.

For now, I'll keep it by my desk, at the ready, for the next time I suffer from scrivener's palsy (see writer's cramp) and feel like a trip back in time.

Photo by Amy Jeter Hansen