Neuroscientists have lots of ways to track brain activity at the level of individual neurons firing off electrical signals to each other, but they all share the same basic problem: whether it involves electrodes, chemicals or genetic modifications, every method developed to date is in some way invasive. Now, researchers may have found a way around that, using nothing more than light.

The key is that when neurons fire, they become a tiny bit thicker than usual. In principle, researchers could measure that change in thickness using a technique called interferometry, which uses laser light to detect tiny changes in the distances between two objects or, sometimes, tiny changes in the thickness of an object. (Caltech has a good explanation of how basic interferometry works.)

You can read more about that in an article I wrote for Stanford News, but here I want to tell you a different story, a story about the minor geek out that ensued as Daniel Palanker, PhD, explained his lab's methods to me in his office one afternoon.

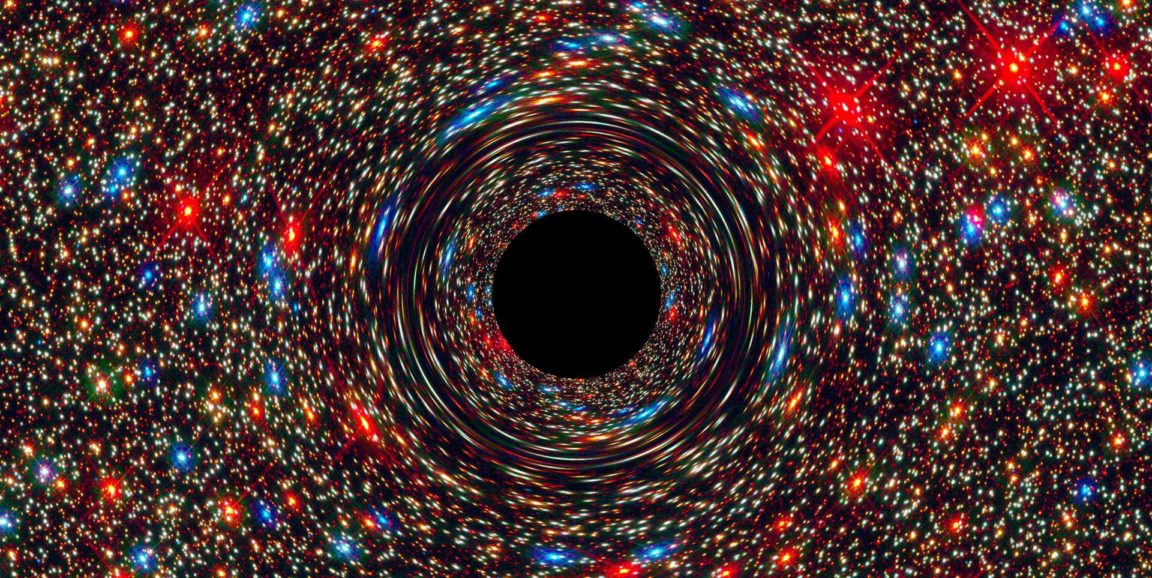

Standing in front of his whiteboard, I realized I'd seen quite a lot of it before — back when I worked on ways to detect the gravitational waves shot out into space as stars fall into supermassive black holes.

You are probably wondering what on earth changes in neuron shape have to do with gravitational waves. The answer lies in how gravitational wave detectors and the Palanker lab's methods work, and here they have two big things in common.

The first, more obvious connection is interferometry itself. Gravitational waves move things around by a preposterously tiny amount, thousands of times smaller than the nucleus of an atom. While a lot larger than that, the change in the thickness of a neuron when it fires is still pretty small, just a few times the width of a single hydrogen atom. Either way, interferometry is pretty much the only method capable of detecting such tiny fluctuations.

Palanker pointed out the second, less obvious connection: noise, or more bluntly, the fact that everything around us, including gravitational wave detectors and neurons, is constantly wiggling. Although we never feel all that wiggling, it's substantial enough that if you look at the signals in a gravitational wave experiment or one of the Palanker lab's neuron-firing measurements, it's near impossible to see in the raw data anything other than the wiggling.

Fortunately, astrophysicists and neuroscientists alike came up with a solution, known as a template. In the case of gravitational waves, theorists worked for decades to figure out what gravitational waves ought to look like — a template — then let experimentalists go looking for them in the data.

The same basic idea applies to neurons, although it's actually much harder to calculate how a neuron's shape changes as it fires. Instead, Palanker's team used electrodes to figure out when neurons fired, then looked at their interferometer data to see how neurons changed shape. After looking at 5,000 or so neuron firings, they had enough data to build a template. And with that template, they showed, they could look through raw data to see neurons firing, with or without an electrode as backup.

If the connections between neuron firing and gravitational waves seems a little like dumb luck, well, in a way they are. After I mentioned my background in physics, Palanker told me he wasn't sure the project would have happened without his own, slightly unusual background.

Although he is now is a professor of ophthalmology and spends a fair amount of time thinking about neurons, he was trained as an applied physicist and knew a lot about optics and interferometry as well. From that vantage point, he says, he could see how to combine a variety of techniques and do something no one had done before — literally watch, with little more than light and a few simple pieces of optical equipment, as neurons fire.

Image by NASA / GSFC