I knew Mallory Smith as an enthusiastic human biology student who graduated from Stanford in 2014. I also knew her as a young woman with cystic fibrosis. She died on Nov. 15, 2017 at age 25 from complications of the disease.

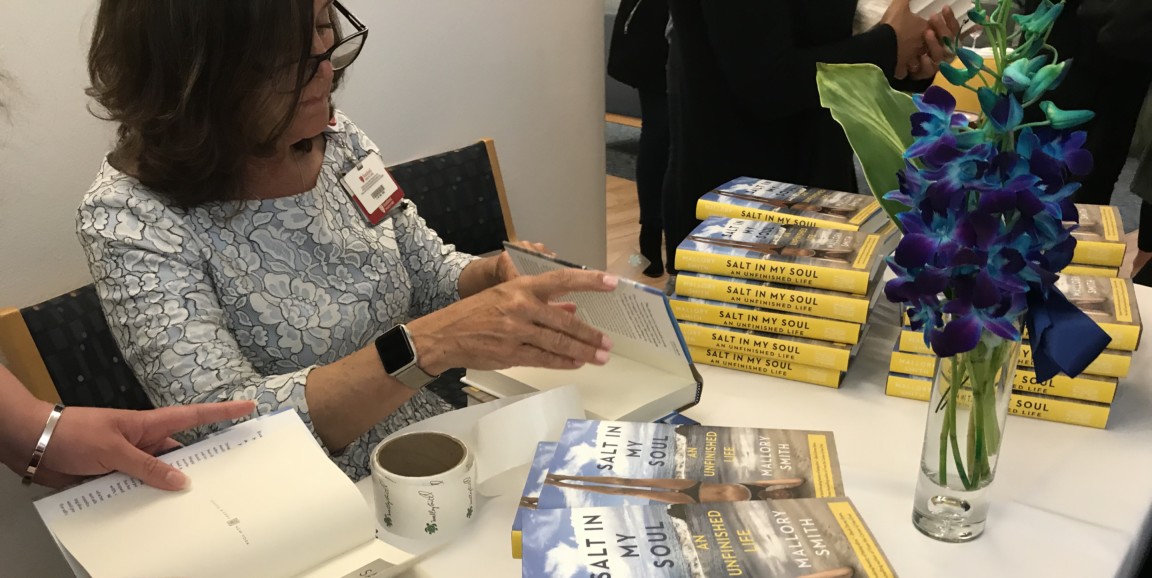

So I was eager to attend a conversation hosted at Lucile Packard Children's Hospital Stanford with her mother, Diane Shader Smith, who advocated ferociously for her daughter during her life. After Mallory's death, Diane helped shape the journal Mallory had kept since age 15 into a posthumous memoir, Salt in My Soul, An Unfinished Life.

At the event, attended by about 90 nurses, doctors, professors, members of the cystic fibrosis community and others, one of Mallory's physicians, David Cornfield, MD, spoke with Diane about Mallory's life, the book, hope and chronic illness.

But as I sat in the auditorium, I realized it was not that long ago that I had the chance to sit with Mallory. I'm a senior producer with the Stanford Storytelling Project and Mallory and I were discussing how to best incorporate audio recordings from a recent hospitalization at Stanford into her senior reflection project. She was crafting a story using a braided narrative structure, telling two stories in parallel. One story told of the slow destruction of the Hawaiian ecosystem. Swimming and surfing in the sea, her cough improved. The second told of her declining lung function.

As we sat together, she played a track on her laptop that she'd recorded of a breath test. I put in earbuds and listened to a painful sounding hacking cough. It was shocking to hear. She looked so healthy.

But, I knew even then that she wasn't.

When she was 12, Mallory caught a strain of Burkholderia cepacia bacteria. "Over time the bacteria becomes resistant to all antibiotics," Diane said. "Sometimes it kills patients quickly but a lot of times you get about 10 years and the repeated antibiotic courses just stop working altogether. And that is what happened with Mallory."

A few years after graduating college, Mallory's health declined. She needed a lung transplant.

The University of Pittsburgh agreed to take on the complex surgery, but the family was warned they still faced barriers: "They said don't get too excited because you're an out-of-state out-of-network situation and your insurance is not going to say yes," said Diane.

Mark Smith, Mallory's father, is a lawyer, and Diane is a publicist. Between the two of them, they were going to get that approval to save their daughter's life. "But they said no," said Diane. Mallory and Diane moved to Pittsburgh to wait for donor lungs. Her mom continued the battle with their insurance and Mallory gave Diane the password to her journal, just in case.

"Our miracle came in the form of the father of one of Mallory's best friends who happened to play golf with somebody at Blue Cross, called in a favor and the next thing you know, the evaluation was approved. Mallory knew that she was incredibly lucky."

"To a patient with end-stage lung disease, that phone call that you get telling you your lungs are available can come days, weeks, months or years after you're listed and once you're listed you can't do anything -- take a shower, go to the movies, sleep through the night, without worrying that you're going to miss that call," said Diane.

Mallory got her call on Sept. 11, 2017.

"Breathing with new lungs after the year and a half that we had was quite spectacular. Literally two weeks later we were home. We dared to dream about a new life. But just a few weeks after that, Mallory was readmitted for pneumonia and at that point, doctors started preparing me for the worst," said Diane.

At the time Mallory was enduring grueling, tenuous recovery from her lung transplant, I was visiting the North Shore in Oʻahu and scuba diving. Submerged in salty turquoise water, I thought often about Mallory. I looked for the honu, the large Hawaiian sea turtles that paddled effortlessly under the waves.

I wanted to share the experience with her and tried to text Mallory, not realizing her immediate predicament. She was unable to respond.

Diane closed the event by revealing the biggest surprise she had found in the journal:

Her facade of perfection masked a darker truth about what she really was living with. She used her journal to express her anxiety, her loneliness, her fear of the disease, her shame about her body and its failings. The difficulty of what it was like to straddle the sick and the well-world, to watch her friends move on in life, as she knew she would never be able to. But also the importance to her of deep and meaningful friendships.

Mallory was incredibly astute and in the pages of her journal she writes about large systemic problems and then also small problems. There was the playful writings of a teenager, the somber insights of a young woman facing death and no expression of anger at me which was incredibly precious and unexpected, and the thing that has kept me going.

From the event, I was blown away by Diane's love and protection for her daughter and how Mallory represents the voice of so many people with severe, chronic illnesses who, in addition to their illnesses, must struggle to navigate the health care system. This book amplifies their voices. Mallory is gone, but her wisdom, and the kindness she bestowed upon others, endures.

Photo courtesy of Lucile Packard Children's Hospital Stanford