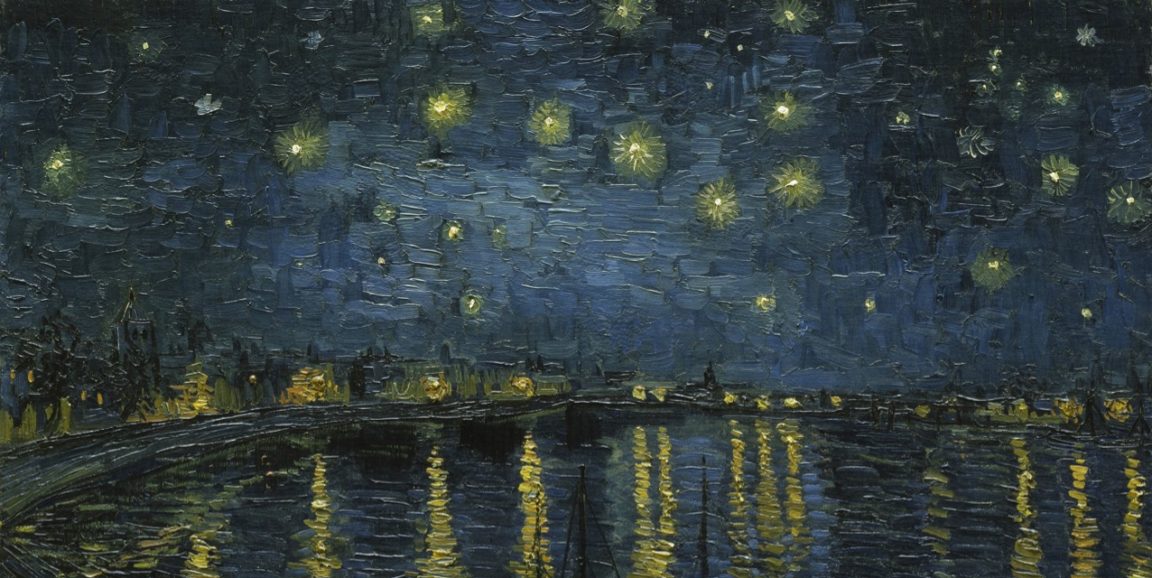

My first glimpses of my son after he was born were of a glowing infant. Like his father and older sister, he had fair skin, in contrast to my olive tone. Yet even compared with his sister, his skin seemed to beam light rays. Over time, he has developed many freckles on his face. We lovingly refer to them as his "stars," like the dots of paint that make up the sky in Vincent van Gogh's 1888 Starry Night Over the Rhône.

It's important to me to use accurate medical terminology when discussing body parts and functions with my children, because I firmly believe that health literacy lays a foundation for healthy conversations and behavior. My insistence on that accuracy was made clear one day when a preschool classmate of my freckled son pointed to their pregnant teacher and shouted, "Ms. Ava has a baby in her stomach!" My son proudly announced, "It's not in her stomach, it's in her uterus!" Yet, we still refer to his freckles as stars.

When he was 5 years old, we noticed a new star on his nose -- a black one. His face full of freckles -- uniformly tan, clearly bordered and individually symmetric -- now had a hauntingly dark and sinuous imposter. We worriedly watched it for a month. It grew. So, we scheduled a biopsy.

I was determined to make the experience as tolerable as possible for my son. As a physician, I could remember when someone had to hold still a screaming infant while I performed a lumbar puncture or a crying toddler while I placed sutures to close a chin laceration. So, I planned for anything that might help avoid that discomfort: the appeal of a Star Wars movie he wasn't yet allowed to see; a lollipop during the procedure; me showing trust in all of my son's dermatology caregivers; and sharing a play-by-play of what to expect during the procedure.

But I wondered if my desire to be medically accurate might not be best when describing the procedure to him. Would words like "needle," "cut" or "punch biopsy" arouse anxiety for him? Because the procedure would be on his face, I knew he would see the instruments. What in his 5-year-old world would be similar enough to a skin biopsy?

Pencils and erasers.

I told him the story that this new star on his face should be erased to keep him safe. That the doctors would first put medicine (topical anesthetic) on his nose to make the mark easier to erase. That during the erasing he would feel a sharp feeling for just a second (the injection of local anesthetic) and after that maybe a pushing which would be the erasing itself (the punch biopsy).

I told him that the doctors use fancy silver erasers so he wouldn't be surprised by metal appearing near his face. And, I told the doctors our story before our biopsy visit, and asked them to use the word "erase" instead of "cut" or "punch biopsy." They obliged, with some skepticism I imagine.

During the procedure, my son didn't flinch. It may have been my son's personality, it may have been the dermatologist's skill and it may have been the other distractions that allowed the biopsy to go well. But I also feel that the metaphor of the eraser and the carefully chosen words and story were influential factors.

Sometimes, I wonder if my son will understand that for his biopsy, I didn't use only medically accurate words with him. Since the pathology was benign, we haven't had to return for follow-up visits with the dermatologist. I recently asked my son what he remembers of the biopsy day, two years ago. I know some day, he'll know about the process more clearly and may have more questions about what exactly happened on his nose. But for now, he remembers the doctor touching his face and getting to watch the big kid movie. And I remember how that story supported him through a challenging procedure.

Our experience reinforced for me that when relaying health information, an emotionally moving and relatable story is more motivating than facts alone. And when the narrative connects us to a new experience by reaching back to one we've heard before, it's especially powerful.

In the care of ourselves, and of each other, we need analogy, metaphor and story. I know now that we can accurately know what our body parts are called, how they work and how to keep them working -- and yet still imagine stars on our faces.

Diana Farid, MD, MPH, is a writer and physician. She cares for patients at Stanford's Vaden Health Center and is a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Medicine. Her debut picture book, "When You Breathe" (Cameron + Kids), is scheduled to come out in fall 2020. When not doctoring or writing, you can find her in a grove of towering redwood trees, making music with her husband and four children. Follow her on Twitter at @_artelixir.

This piece is part of Scope@10,000, a series of original narrative essays from writers, physicians and thinkers in honor of Stanford Medicine's Scope blog publishing 10,000 posts.

Vincent van Gogh's Starry Night Over the Rhone courtesy of Google Art Project