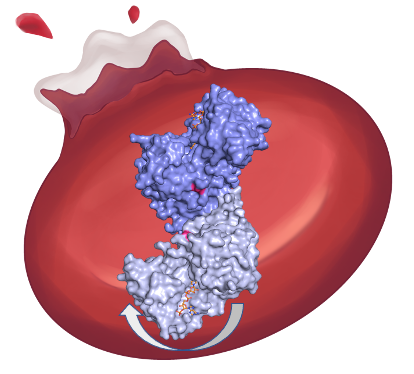

In its most severe cases, G6PD deficiency -- the world's most common blood disorder -- can cause jaundice, ruptured blood cells and kidney failure. So it was certainly satisfying when Naoki Horikoshi, PhD, a visiting researcher at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, and colleagues published results on the structure of mutated forms of the G6PD enzyme.

From those results, researchers have learned new clues that could down the road lead to new drugs for G6PD deficiency, findings I described recently in a story for SLAC.

But the study was also an opportunity for young scientists to learn how to do that kind of research. Over the past several summers, one undergraduate and three high school students worked with Horikoshi, Soichi Wakatsuki, PhD, at SLAC, and Daria Mochly-Rosen, PhD, at Stanford, to learn the ropes of X-ray crystallography, a standard technique for revealing the structure of proteins involved in biology and disease.

Using X-ray crystallography

Each student, Horikoshi said, took on one G6PD mutation.

Even for more advanced researchers, the steps involved in determining the structure of a protein can be a challenge.

To study just one protein, a scientist must first purify a sample, then grow a crystallized form of it -- a process that typically proceeds in fits and starts until one can figure out the perfect procedures for working with a given material. Once the crystal is grown, researchers fire a beam of X-rays at it and analyze the patterns of X-ray diffraction that emerge to infer its structure.

It can be long and frustrating even for seasoned researchers, so the first time a young scientist gets it to work can be especially pleasing.

Savoring success

Xinyu Xiang, who was an undergraduate at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore at the time she worked on the project, said that she had previously tried to grow protein crystals and analyze them, but nothing had worked out. Succeeding with G6PD, she said, "was really proof I had learned something from my past failures, which was really motivating."

In fact, she was sufficiently excited that she had a 3D model of her protein made and had it sent to her parents back home.

Andrew Chiang, a student at Stanford Online High School, shared that enthusiasm. "The most exciting part was actually seeing a protein crystal I grew," he said. "It was really beautiful, like a jewel you'd put on a ring."

Both Xiang and Chiang said they were motivated to take part in the research by an interest in biology and a desire to help work toward treatments for disease, and both are hoping to come to Stanford in the next year to advance that goal. Chiang said that he had one wanted to focus on engineering, but a biology class planted the idea of applying engineering to health "to create things to help people," Chiang said.

Horikoshi said that since there were several undergrads and high school students working on parallel projects, they had a chance to learn from each other and advance science in the process. "Even though they only stayed two to three months, they were so active and motivated. They really helped to push this project forward."

The project was a positive experience for Horikoshi as well, he said. "I have had a great opportunity to mentor them."

Top photo of SLAC office buildings by Linda McCulloch/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory; Center image courtesy of Mio Wakatsuki, from protein images by Naoki Horikoshi/SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory