Everybody loves a good origin story, right? In the most recent issue of Stanford Medicine magazine, I wrote about the career path of Stanford dermatologist Anthony Oro, MD, PhD, who, in the late 1980s, began entering high school science fairs while a student at Gompers Preparatory Academy in San Diego. One project studied how the loss of the ozone layer, and the subsequent increase in people's UV exposure, was likely to affect skin cancer rates.

"I didn't realize at the time, but I guess I was a budding dermatologist even then," Oro remarked.

Since his science fair days, Oro has built a career studying how basal cell carcinomas arise and, often, grow to evade one of the most successful ways to treat them. Recently, he and graduate student Catherine Yao showed that the cancer cells can assume an entirely new identity -- a feat common in developing embryos but previously thought to be out of reach for mature cells.

These freshly minted cancer cells are drug resistant and difficult to treat. And they sometimes occur even before treatment has begun.

"Cancer biologists might say the cells want to hedge their bets while staying alive," Oro said. "If you can diversify your portfolio so that a subset of your cells can withstand the treatment, you're golden."

Fruit fly chronicles

Oro and Yao's discovery hinges on a cellular mechanism called the hedgehog pathway that was first studied in fruit fly embryos. The pathway ensures that the legs, antennae and wings are arrayed properly on the abdomen, thorax and head.

From the article:

Like a Rube Goldberg machine, in which a ball rolling down a track triggers weights to fall, dominoes to topple and pendulums to swing, cellular pathways comprise several successive steps that deliver a message or a signal from one location -- often outside of the cell -- to another -- often the cell's nucleus.

Each step triggers the next so a cell can respond quickly and efficiently to changes in its environment.

After completing medical and graduate school training at UC San Diego, Oro joined Matthew Scott's laboratory at Stanford to learn how the hedgehog pathway functions in more complex organisms. Their research identified the role of the pathway in basal cell carcinomas and led to the development of a drug called vismodegib that blocks a protein called smoothened that blocks an early step in the pathway. At first, vismodegib stops many basal cell carcinomas dead in their tracks. But within a few months, the cancer returns in as many as 1 in 5 patients, many of whom are then resistant to the drug.

A tricky lane change

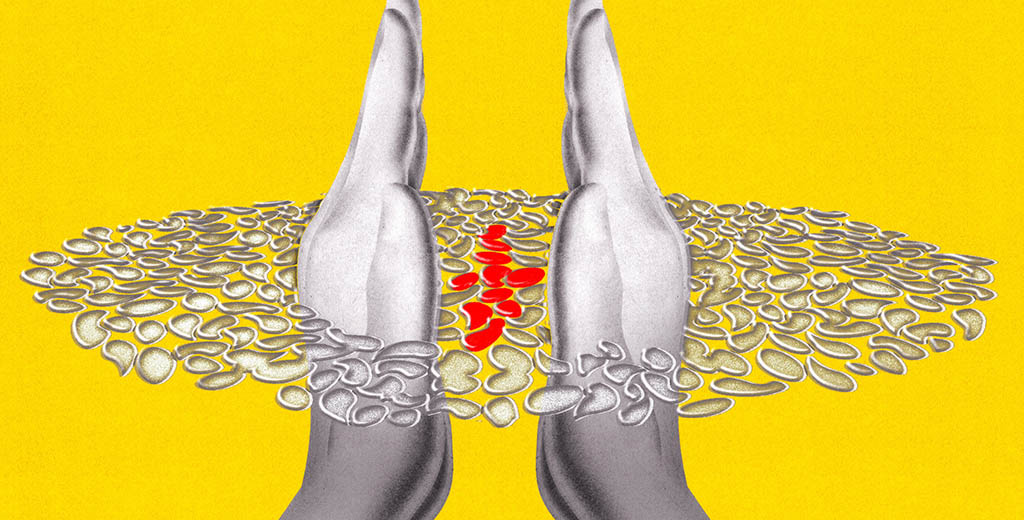

Oro and Yao found that the newly resistant cells occur when the original cancer cells slide sideways along a common developmental pathway to more closely resemble a related type of cell that relies on a different way to activate the hedgehog pathway. Oro likens the evasive maneuver to changing lanes on a freeway to avoid a slowdown.

"Here we can actually see cells changing lanes, or fates," he said. "This allows them to live even though the upstream portion of the pathway is being blocked."

The discovery could point to the beginning of the end of drug-resistant basal cell carcinomas, the researchers believe.

"Finally, we've shown, in great detail, the escape route these cells have been using and how it mirrors normal development," Oro said. "If we can convince the drug-sensitive cancer cells to 'stay in their lane' by making it impossible for them to switch identities, or forcing them to switch back, we could transform the treatment of this disease."

Image by Brian Stauffer