The overhead announcement rings through the halls: "Trauma 95 arriving in room Alpha 2 for team AY." Al'ai Alvarez, MD, the attending night shift physician at Stanford Hospital, knows that's a call for him and his team - it signals a patient is arriving in the emergency department's lowest tier of severity.

There's a hum about the emergency room -- each person tending to their own role. A resident physician scrupulously examines the patient from head to toe looking for injuries, loudly calling out their findings. People move with quick, ordered footsteps, shuffling in and out of the trauma bay filled with clicks, whirs and beeps.

This happens repeatedly throughout the shift, one patient at a time. Shortly after, another announcement is made, this one, a patient in cardiac arrest. With little notice, the team reassembles to perform the same assessment. Like activating a muscle memory, the team immediately goes through an orchestrated checklist of protocols, led by the chief resident physician.

The team activates the five Hs and five Ts (checking for things such as hypothermia and toxins), a mnemonic device that facilitates a resuscitation. Eventually, someone announces the patient has regained a pulse.

A handful of people fill the resuscitation room: Alvarez, plus three emergency medicine resident physicians at various stages of training, a respiratory therapist, three nurses, at least two technicians on chest compressions, a pharmacist and the social worker. After the resuscitation, the team disperses, each one going their own way to see their next patient.

In emergency medicine, this rollercoaster of calmness and organized chaos happens unpredictably throughout every shift, said Alvarez, a clinical associate professor of emergency medicine. "Quickly resetting myself from one resuscitation to the next is key," he said. "There's a lot of uncertainty, including the nature of patients arriving in the emergency department, so it helps to at least know that I can count on the people I'm working with."

Night in the ER

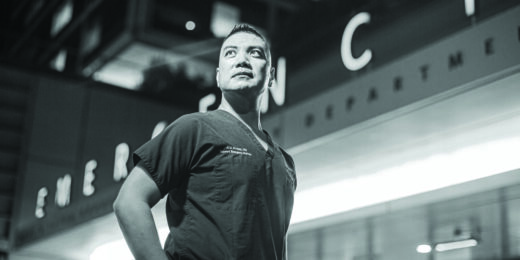

On any given night, you can find emergency physicians like Alvarez in the Alpha Zone of the adult emergency department of Stanford Hospital, an area about the size of a football field, in which doctors see anyone who comes through the door. Alvarez is one of the department's night shift attending physicians and he carries a necessary sense of urgency, yet to anyone who knows him, a levelheaded, even jovial, demeanor also persists.

During high-intensity resuscitations, the adrenaline and racing heart never quite go away, even with experience, said Alvarez. But he does find ways to center himself.

"I visualize my role during the resuscitation," Alvarez said. "Mentally planning resuscitations helps me minimize stress. I also pay attention to the dynamics in the room, recognizing emotions. I slow down the tempo of my speech to not add to the chaos while also managing my adrenaline."

And he has another trick. He wears four silver rings that he uses to pace himself: Taking them off before putting on gloves gives him a moment to mentally pause before he jumps into action.

Alvarez has been a night shift worker for over 10 years -- by choice. So what does it mean to care for patients -- and for yourself -- during the wee hours of the night?

The team tends to be a smaller and tighter-knit, autonomous and agile group that relies on trust built over years. For instance, a day shift health care worker might ask an ear, nose and throat specialist to do a procedure. But come sundown, that specialist has gone home. Often in the ED, he steps back to encourage the Alpha chief, a fourth-year resident with the responsibilities of a doctor, to direct the bustling scene.

"My hope is for my residents to be trained to be as independent as possible so that wherever they go, they can take care of patients safely and confidently," Alvarez said.

Why the nocturnist lifestyle

As a kid, Alvarez observed his mom work night shifts. "She's an inspiration," he said. His mom raised Alvarez and his younger brothers on her own as a night shift nurse. Working those shifts gave her time to be with her three children during the mornings and early evenings and to sleep while they were at school.

To ease his transition to his own night shift (he works from 10 p.m. to 7 a.m.) Alvarez, who is the director of wellbeing for the Department of Emergency Medicine, practices self-compassion, or the ability to be caring towards oneself, particularly during hard times. Proactive mental health maintenance includes taking a break to attend to their needs or pausing to celebrate small victories throughout their shift, he said.

High-performing teams check in and express appreciation for each other, Alvarez said. That kind of support, he adds, fosters a sense of belonging and can go a long way to improve well-being, especially during a strained schedule working deep into the night.

"Our community, including our patients, expects those of us in the health care space to be superhumans," Alvarez said. "But that's just not the case; we are just as human as everyone else."

This acknowledgment, paired with self-compassion, he said, helps him find his meaning in medicine, particularly on the night shift.

Photo by SeanPavonePhoto