When walking through different parts of a neighborhood, how do you feel? Comfortable and relaxed, or stressed and on-alert? And how do these different environments -- over days or even years -- impact your well-being?

A new Stanford study explores how to answer these kinds of questions using citizen scientists, as recently reported in International Journal of Health Geographics. To learn more, I spoke with lead author Ben Chrisinger, PhD, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Stanford Prevention Research Center.

What inspired you to study the built environment and health?

I've always been fascinated by how and why we perceive different neighborhoods as safe or unsafe, welcoming or unwelcoming, and attractive or unattractive. If we can develop a more granular understanding of where we feel certain ways, and why, it's possible that we can improve urban design.

Chronic stress contributes to a number of negative health outcomes, ranging from decreased immune function to cardiovascular disease.

Understanding what exactly contributes to stress in different places can be valuable information for individuals. But we also think there's great potential in pooling these stress data across many individuals to see if common themes exist. Urban planners, policymakers and developers could learn from these themes to better promote health in their communities.

How did you conduct your recent citizen scientist study?

We partnered with an urban design and planning nonprofit, Place Lab in San Francisco. They recruited eight women and six men in their 20s and 30s who lived locally. We had all the volunteers do the same 20-minute walk in the Hayes Valley neighborhood.

We used a citizen-science method called Our Voice, developed by the Healthy Aging Research and Technology Solutions Stanford research group led by Abby King, PhD. Individuals use a smartphone app to take pictures and record audio narratives of their neighborhoods.

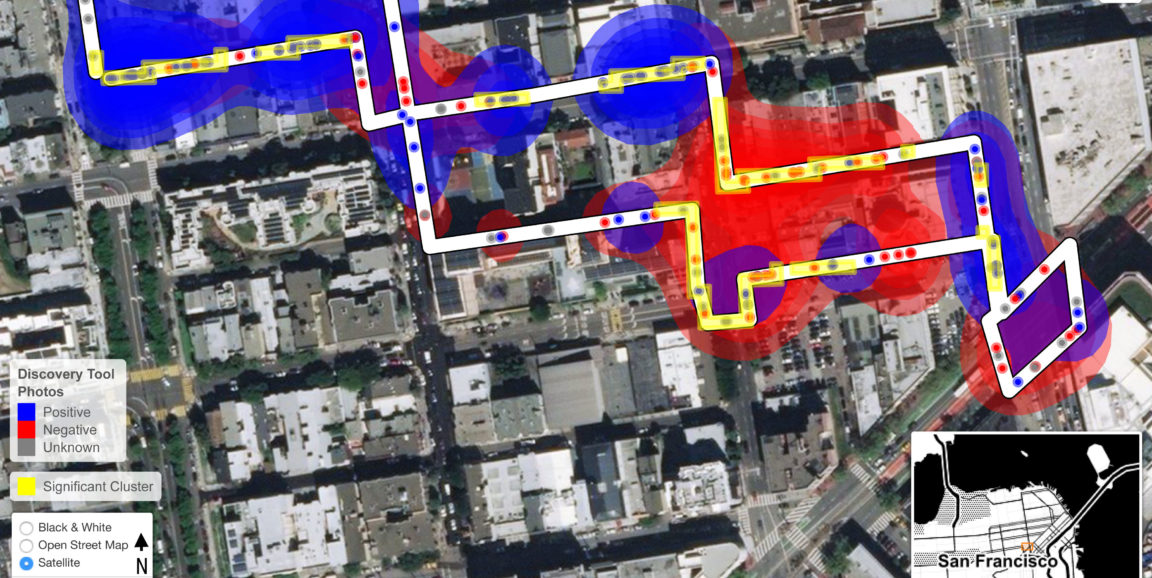

We asked people to document things along the walk that they thought were contributing or detracting from their well-being. Their phone app recorded where they took their pictures and audio narratives. Everyone also wore a sensor on their wrist that measured time-stamped biometric data -- including blood volume pressure, heart rate, skin temperature and electrodermal activity as a proxy for stress -- to show how their bodies responded to different environments.

We then created a web platform to share back the participants' photos, transcribed audio and biometric data superimposed on a map.

What did you find?

The phone app data showed that participants often talked about traffic, noise and whether they felt safe as a pedestrian. Even in high-volume areas, people also talked about the aesthetic qualities of streets and historic buildings. It appears that it's not just parks that are stress reducing -- quiet areas might also be important. We need to do more research to understand the elements that provide a break from the urban environment.

Our exploratory statistical analyses revealed that, on average at the group level, there were significant associations between participants' electrodermal activity and the built-environment characteristics. However, it's clear that these models explain some participants' data much better than others. One possible explanation is that we're leaving out some influential neighborhood variables.

What's next?

We want to do this again with more people all walking a smaller section -- like one alley or a pair of streets -- so we can dig deeper into what explains the differences between people's perceptions of specific places.

We also want more diversity in the age, race and ethnicity of our participants. We know this is important from earlier citizen scientist projects. For example, a previous study showed that kids take pictures of graffiti and see it as a good thing, as art, whereas older adults see it as vandalism.

Map of San Francisco neighborhood that shows negative neighborhood photos in red and positive ones in blue courtesy of Ben Chrisinger