A new study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences has something to tell us about why, at a certain point in our lives, we all wind up looking for our sunglasses for ten minutes before finding them on top of our heads.

As we age, our brains become vulnerable to diseases - notably Alzheimer's and Parkinson's - while remaining prone to haphazardly incurred injuries and, more subtly, to the wear and tear of ordinary everyday experience.

Strikingly, even among the majority of us whose brains remain relatively healthy, our memory and other mental functions decline. The reasons for this are largely unknown, but the new study offers a potential clue.

First, a bit of background. In January 2017, Stanford neuroscientist Ben Barres, MD, PhD and his colleagues reported in Nature that they'd identified a common thread tying together Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and Huntington's diseases, multiple sclerosis and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. That thread? The conversion of a normally very helpful type of brain cell into a menace.

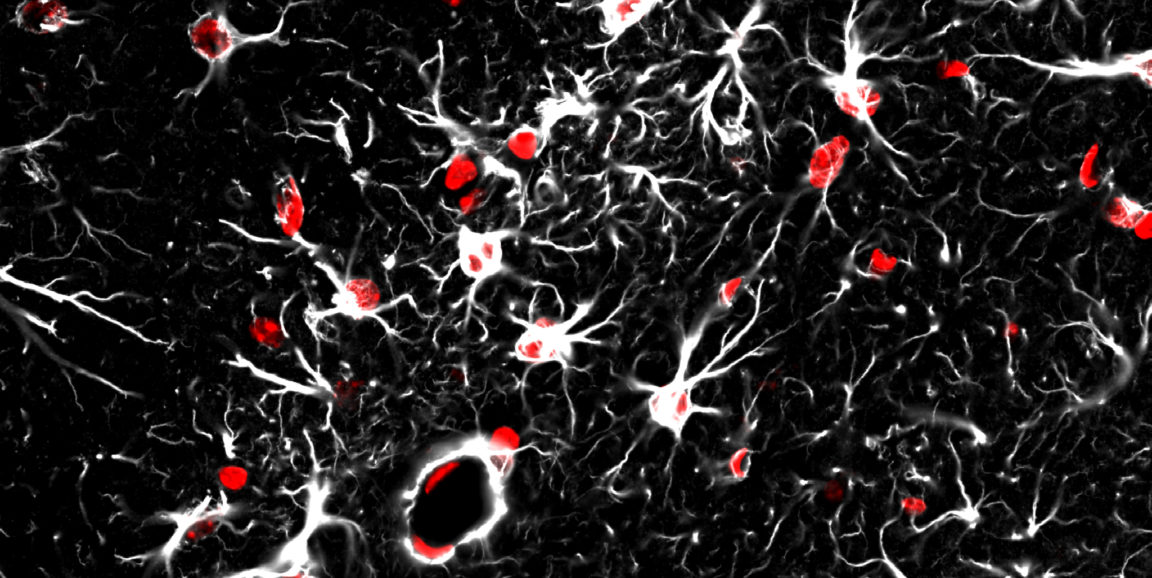

This Jekyll-and-Hyde transformation occurs among star-shaped brain cells called astrocytes, which actually outnumber their far-more-celebrated near neighbors, nerve cells (a.k.a. neurons), in the brain four-to-one.

Once considered not much more than subservient handmaidens that dutifully mopped up neurons' excreta and supplied them with various molecular bonbons, astrocytes in fact not only serve neurons but, in many ways, rule over them. For example, astrocytes play a critical role in building or chopping up contact points through which neurons communicate with one another. These connections, called synapses, encode our memories, our skills, our emotions and our thoughts. Don't leave home without them.

The Barres team showed, in their Nature study, that under certain inflammatory conditions, astrocytes go rogue. They not only go on strike but secrete toxic material (identity still to be revealed) that kills somewhat frayed but still functioning neurons. These "Bad Astrocytes" were found lurking in the vicinity of the lesions associated with all the neurological disorders mentioned above. Circumstantial evidence, yes, but enough to fuel a conviction in the field of astrocytology. (I made that word up.)

The researchers also sussed out the environmental conditions under which good astrocytes go wrong. That, or an antidote to the Bad-Astrocyte toxin, could translate someday into once-undreamed-of preventive and curative treatments.

The new PNAS study extends these findings by unearthing Bad Astrocytes in healthy brains, too - and particularly in a couple of brain structures known to be at highest risk of deterioration in healthy aging brains.

This new study's senior author was, again, Ben Barres. Among the names appearing on both studies are those of research scientists Laura Clarke, PhD (the lead author) and Shane Liddelow, PhD.

Alas, Barres passed away in December 2017. Much of what we know today about astrocytes' importance is the direct result of his research over a decades-spanning career. Much of the rest is being discovered by his trainees at Stanford and elsewhere.

Image by Jason Snyder