Her goal is straight out of science fiction: Create artificial skin, capable of the human sensation of touch.

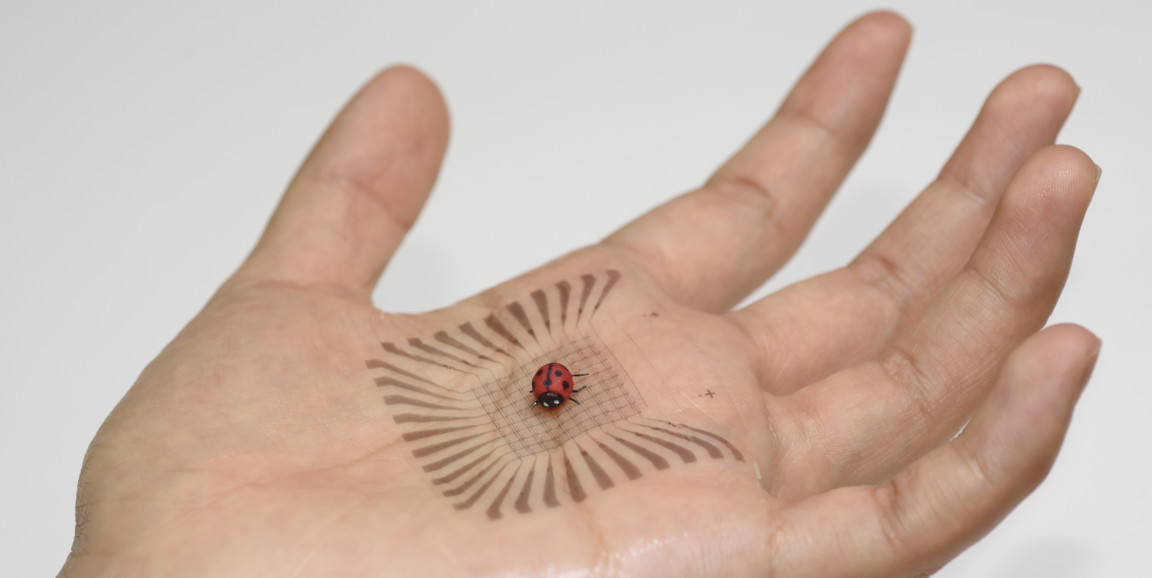

After two decades, Stanford chemical engineer Zhenan Bao, PhD, has reached a milestone in that journey. She and her team have developed a flexible, stretchable, polymer circuitry with integrated touch-sensors that are sensitive enough to detect the tread of a ladybug.

They describe the material and a method they devised to mass-produce it – another advancement – in a new paper in Nature.

From the Stanford release:

The team has successfully fashioned its material in squares about two inches on a side containing more than 6,000 individual signal-processing devices that act like synthetic nerve endings. All this is encapsulated in a waterproof protective layer.

The prototype passed rigorous durability tests, and the new material and manufacturing process together could pave the way for innovations in everyday gadgets in the near term. (Think foldable, stretchable touchscreens for smartphones, or even electronic clothing.)

In the long term, this breakthrough could open the door to the creation of synthetic skin, which would restore a sense of touch for people with prosthetic limbs.

The release explains:

Bao’s hope is that manufacturers might one day be able to make sheets of polymer-based electronics embedded with a broad variety of sensors, and eventually connect these flexible, multipurpose circuits with a person’s nervous system. Such a product would be analogous to the vastly more complex biochemical sensory network and surface protection 'material' that we call human skin, which can not only sense touch, but temperatures and other phenomena, as well.

Photo by L.A. Cicero