The preferred treatment for HIV can reduce cancer incidence among infected individuals, a new study shows. However, on a more sobering note, even individuals for whom the therapy is successful retain elevated rates of cancer over those who are not infected.

Antiretroviral therapy, a breakthrough treatment for HIV infection, suppresses the levels of circulating HIV viral particles in the blood. When it works, it results in radical improvement in health and life expectancy for HIV-positive individuals.

New confirmation, at least with respect to cancer, comes in the form of a very large study comparing health outcomes of 42,441 HIV-positive U.S. armed-forces veterans with 104,712 HIV-negative vets over a 16-year period between 1999 and 2015. The new study was "the first to examine the effects of prolonged periods of viral suppression and potential cancer prevention benefits," says Stanford population-health scientist Lesley Park, PhD, of the study, which was funded by the National Institutes of Health, led by Park and published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Some 9 percent of the HIV-positive veterans followed in the study eventually contracted cancer of one type or another, as opposed to 6.8 percent of uninfected participants. Drilling down, the investigators observed substantially lower cancer rates among HIV-infected individuals who had achieved long-term viral suppression than among those who hadn't.

More than half of the HIV-positive individuals in the study achieved long-term viral suppression at some point. But even among HIV-positive patients who had attained long-term viral suppression, overall cancer rates remained about 50 percent higher than those of uninfected veterans.

In prior work, Park and her colleagues have shown that the prevalence of oncogenic, or cancer-causing, viral infections is extraordinarily high among people infected with HIV. In the new study, successful antiretroviral therapy profoundly improved the prognosis for such people. Rates of certain virally induced cancers whose occurrence in an HIV-positive individual is sufficient to confer an AIDS diagnosis (for example, Kaposi sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma or invasive cervical cancer) plummeted among those HIV-positive veterans whose antiretroviral therapy had succeeded in inducing long-term viral suppression.

Meanwhile, HIV-positive veterans lacking any such suppression developed these cancers at more than 20 times the rate of uninfected veterans. Still, even HIV-infected veterans attaining long-term suppression developed such cancers more than twice as often as uninfected vets did.

The study also showed drops in rates of several cancers that, while not specifically considered markers of AIDS, are associated with viral causation (for example, melanoma, leukemia and cancer of the lung or larynx). Absent long-term viral suppression, HIV-positive patients developed these cancers at nearly four times the rate of uninfected individuals; among those with long-term suppression, the rate was below three times that of uninfected people.

One upshot of the study, according to Park: "Clinicians and patients should be even more motivated to adhere to treatment to achieve long-term viral suppression."

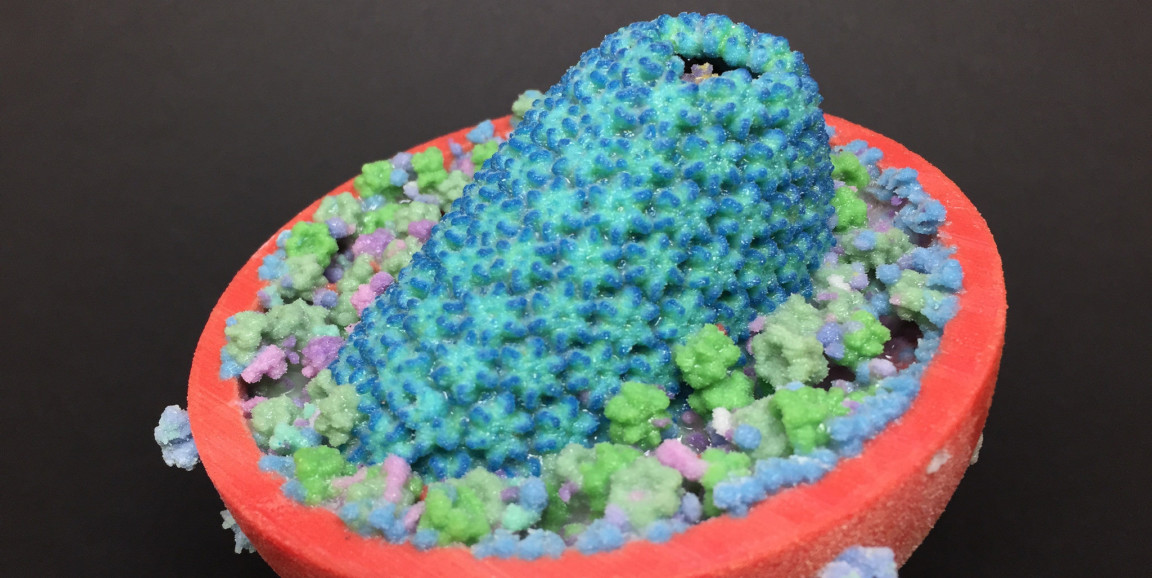

Image of HIV virus by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH