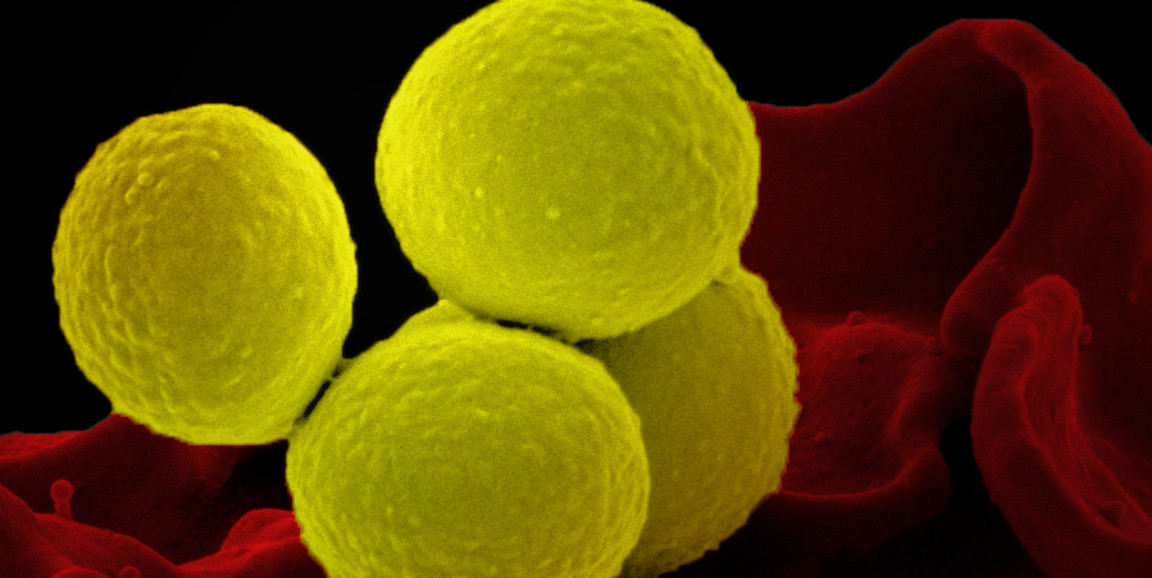

The widespread use of antibiotics has led some bacteria to become increasingly stubborn to treatment. One of those bacteria is methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, known as MRSA.

MRSA infections often begin on the skin and can lead to sepsis, bloodstream infections, pneumonia, and even death.

Now, a team of Stanford researchers has developed a new approach to attack MRSA, a Stanford News article explains. Rather than develop a new antibiotic, the scientists created an attachment to a current common antibiotic that makes it hundreds of times more effective.

The work was published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

The small molecular attachment known as r8 aids the common antibiotic vancomycin in penetrating through a biofilm (like dental plaque) that surrounds the bacteria, the article explains. The molecule also encourages the drug to linger, said graduate student and co-lead author Alexandra Antonoplis, which allows the antibiotic to more effectively kill bacteria that would normally pose extensive challenges for doctors to stop.

Although the study's results don't mean a new antibiotic is headed immediately for production, the chemists emphasize that their findings suggest a new way to approach antibiotic production: "by modifying existing antibiotics with synthetic components to give them new and improved treatment potential." The team believes the same strategy could apply beyond MRSA to boost the efficacy of other antibiotics and fight other stubborn, potentially deadly bacterial infections.

“You don’t have to invent a new drug. You just have to fix the problems with existing drugs,” explained chemist Paul Wender, PhD, a senior author, in the news release.

Photo of scanning electron micrograph of a human neutrophil ingesting MRSA (yellow) by NIAID