Stanford emergency medicine physician Al’ai Alvarez, MD, finished what was in his words, a “rough shift” with five critical patients, including a cardiac arrest resuscitation. It had been a long day and most people in his scrubs might have headed for the metaphorical hills to recuperate. Instead, driving home, Alvarez did what he has done for some time now: he identified events in the day he was grateful for. Then, at home, Alvarez sat down as he often does and wrote letters of thanks to key people on his shift, acknowledging their efforts and the role they played in his day.

“The negative screams at us,” he explains. “We are hardwired to notice the negative. I heard researcher Barbara Fredricksen say that the positives whisper; we need at least three positives to counter every negative.”

When Alvarez first learned about the science of gratitude from Patty deVries of the Stanford LeadWell Network, he was transitioning into a full-time faculty role with Stanford’s Department of Emergency Medicine.

Alvarez had previously worked in Redding in northern California and learned this summer that many of his former colleagues were working close to the Carr Fire. On a quick break during a shift at Stanford, he arranged to send sandwiches to the ED at Redding as “a token of solidarity and gratitude for our common work as crisis managers.” He said the act changed his perspective for the remainder of his shift — he became much more aware of all he had to be grateful for.

Another practice Alvarez employs is a rapid stream of consciousness of thanks, “I say ‘I'm grateful for…, I'm grateful for…, I'm grateful for…’ You can’t be genuinely grateful and unhappy at the same time,” he explains.

Gratitude has been shown to have many lasting effects on the individual, including improved sleep, and reduced cortisol levels and depression. Alvarez also spoke with me about the impact of gratitude on two challenges many physicians fall prey to: low self-compassion and the imposter syndrome.

“Self-compassion is difficult in high-performing individuals,” says Alvarez, who finished three degrees in four years as an undergraduate. “We’re willing to skip lunch or cut short our sleep, anything we can sacrifice in our personal lives to excel. The drive to perfection is unrealistic and leads to anxiety.”

Alvarez, the first physician in his family, is grateful for the opportunities at Stanford, but acknowledges that in an environment of experts, it can be easy to fall into the mindset of believing you are not good enough — the imposter syndrome. “Gratitude,” he says, “humanizes the institution and diminishes feelings of isolation, helping you to establish your place. And gratitude builds connections that foster a sense of belonging critical for physicians in high stress jobs.”

Alvarez credits his mother’s optimistic approach to laying a foundation of appreciation. “She’s always able to look at the positive. She thinks I’m doing amazing things already. Even now, if I don’t get something I was shooting for, she says, ‘Yeah, but you’re at Stanford.’ It puts things in perspective.”

This practice of gratitude is not new for Alvarez. “I didn’t know there was science behind this. I always thought it was just something everyone does, and that it’s the right thing to do.” Alvarez makes a point of thanking his elementary teachers every time he visits the Philippines. Recently, he flew to SUNY Buffalo, his alma mater, to give a lecture on mentorship and the path to medical school. He says his role models are often surprised to receive thanks for what they feel is just their job. At the same time, he understands their reaction.

“I think of the patients I’ve seen who come to the ED with a nagging cough,” Alvarez shares. “I’d tell them their x-ray is normal, and they’d hug me. In my mind, I’m just practicing emergency medicine. I’m thinking, ‘I just gave you an allergy medication, why are you hugging me?’ I thought maybe it was a California thing. I finally asked, and the patient shared that in her mind I just told her she doesn’t have cancer.”

He concludes, “We look at leadership as this grand thing and often take for granted the impact of our role. But you can lead with gratitude. If you take a moment to thank even just three people, you’ll see... you’ve made someone happy. And it’ll make you happy. It’s a ripple effect.”

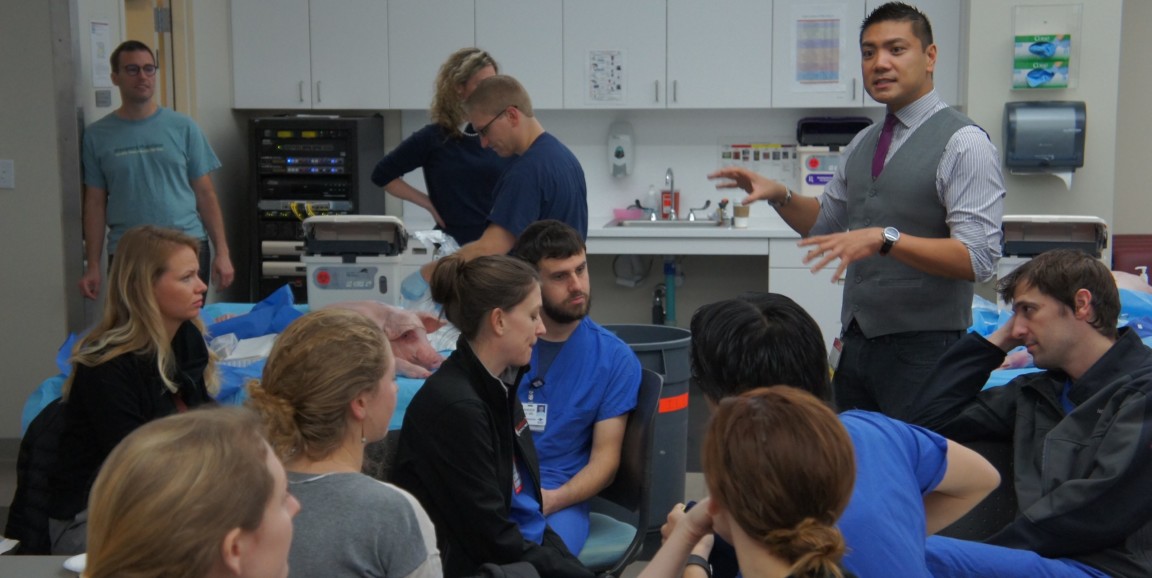

Photo of Al'ai Alvarez preparing residents for a simulation exercise by Susan Coppa