We hear a lot these days about what my mom used to call "good germs" when I was a little kid. She was referring to what's now called the microbiome, the internal ecosystem of mostly friendly microbes we carry around in our gut.

But lest we forget, there are some really bad germs out there, too. One of the nastiest is Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which the World Health Organization blacklisted in 2017 as one of the planet's top three "critical priority" bacterial pathogens in need of some restraint.

P. aeruginosa typically dwells in the air and the soil, which is fine as long as it stays there. But it also holes up in in burns, bedsores and diabetic ulcers, generating chronic wounds that just won't heal. And it infects the lungs of most cystic fibrosis patients who've reached adulthood.

Not only has this goo-coated pathogen grown increasingly drug resistant, but there's no vaccine against it. It turns out, though, that the cellular slimeball has an Achilles heel nobody knew about until Stanford microbiologist and infectious-disease expert Paul Bollyky, MD, PhD, and his colleagues found it, as described in a study in Science.

The secret of P. aeruginosa's uncanny, if unwanted, ability to sustain a chronic infection rests in the fact that it, too, is often infected -- not by another bacteria, but by a virus. In fact, the bug appears to have domesticated its tiny invader and turned it into a partner in crime.

Viruses that infect bacteria -- called bacteriophages, or just "phages" for short -- were first discovered in 1914. As Bollyky told me when I interviewed him for our news release about the study:

We've long known that you've got up to 10 quadrillion phages in your body, but we just figured whatever they were doing was strictly between them and your commensal bacteria. Now we know that phages can get inside your cells, too, and make you sick.

The cells in question are immune cells whose job descriptions include gobbling up single-celled pests (I'm looking at you, bacteria!) and, having ingested them, digesting them and spitting their bits out for the benefit of other immune cells. The latter perform post mortem inspections and -- depending on their job descriptions -- either scrupulously record the pathogen's identifying features for future reference or commence an immediate search for any cells bearing that mugshot.

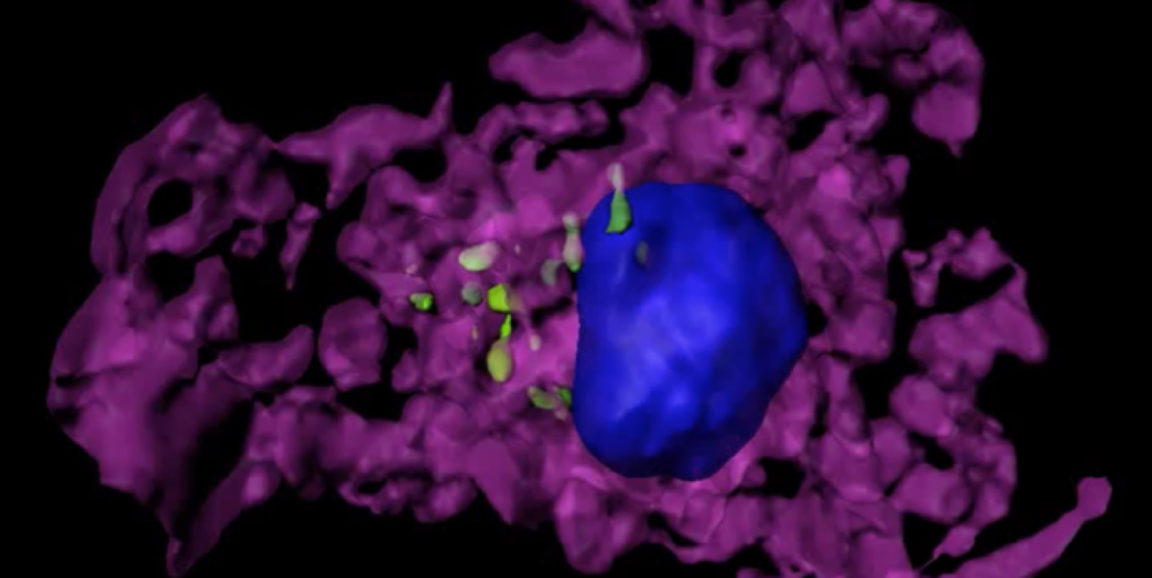

But P. aeruginosa knows a trick or two. Upon parking in a wound or a lung, the wily bug, should it be so lucky as to harbor the phage, sends out multiple copies of it as decoys. [See movie, just below, which shows a wrap-around view of an immune cell (purple) that's swallowed several phage particles (green). The cell's nucleus is blue.]

To make a long story short, after swallowing a phage or two our normally eat-bacteria-for-lunch immune gobblers lose their appetites. They pretty much just sit there shouting for more-expert antiviral assistance, while ignoring the P. aeruginosa in their midst. The pathogenic perp is left to "divide and conquer," as it were.

Bollyky and his colleagues showed that the bacteria is much more infectious when it's carrying the bacteriophage than when it's phage-free. They also created a vaccine against P. aeruginosa's phage, which like a loyal pet sometimes clings to its microbial master's surface -- and inadvertently serves as a laser beacon exposing P. aeruginosa to the wrath of the immune system's fiercest antibacterial warrior cells.

From my release:

Bollyky's vision is to vaccinate people against [the phage] when they're first diagnosed with cystic fibrosis or diabetes, as well as people in nursing homes and hospitals, in order to protect them from P. aeruginosa infections.

Photo and video courtesy of Paul Bollyky