I've spent more time thinking about prostates in the last several days than I have over my entire life.

Last week I was assigned a story featuring genomics research in, you guessed it, prostate biology. What I knew about the gland could basically be summed up in a sentence: Only men have one, and there's some connection to urination.

I admit, it wasn't much to go on, and so began my deep dive into prostate anatomy.

Here are the basics: The prostate is a walnut-sized gland located just in front of the male rectum. The ureter (a duct that carries urine) runs directly through the center of the prostate, meaning that any expansion of the gland squishes the ureter, which can cause symptoms such as incontinence or urinary urgency.

Here's some less common prostate trivia: Did you know they have lobes? Or that prostate enlargement occurs so frequently that most men 70 and older have larger-than-normal prostates? Here's one that Jim Brooks, MD, professor of urology and a lead author of the research, told me in an interview about the study: When prostates enlarge, only part of it grows. Some regions of the prostate remain totally normal.

The condition of enlarged prostates is so common, yet its root causes are still mysterious. In this new study, Brooks and pathologists Jonathan Pollack, MD, PhD, and Robert West, MD, PhD, harness genomic analyses to make inroads to better understand why it happens.

As I explain in our release:

The new study is one of the first to describe a molecular landscape that differentiates enlarged prostate tissue from normal tissue. The team of scientists also discovered that the cell growth behind a ballooning prostate is not uniform. Several cell types comprise the prostate, and abnormal growth appears to come from an outburst of specific sets of cells, rather than an overall increase of all cell types.

The study appears in JCI Insight. Former MD-PhD student Lance Middleton is the lead author.

Through their genomic analyses, the team created a "signature" of sorts that flagged enlarged prostates. In doing so they also discovered two genes that seem to contribute to the development of the condition: CXCL13, which codes for a protein involved in immune cell recruitment, and BMP5, which plays a role in cell identity and development. They even demonstrated a potentially causal role for BMP5.

Whereas CXCL13 effects are complicated to model in the lab, it's relatively easy to manipulate BMP5. So the researchers rigged an experiment to test if adding a BMP5-laden concoction could change the characteristics of normal prostate tissue. They found that healthy prostate samples could be coerced into expressing the 65-gene signature seen in enlarged prostates.

...

'They even start to proliferate a little bit,' Brooks said. 'It's quite remarkable that with this one molecule, we can turn healthy samples into samples that mirror the molecular landscape of an enlarged prostate.'

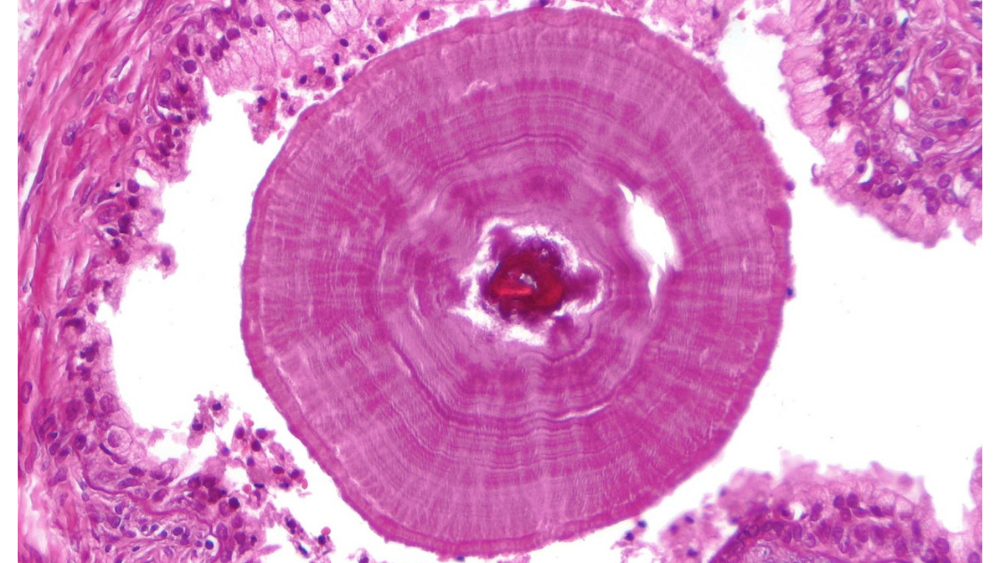

Photo by CoRus13