One of the most striking lessons that I learned when I first joined a lab was that the majority of scientific research is not, in fact, conducted by individual super-geniuses with crazy hair and eccentric, brilliant ideas.

Rather, most scientists are young people -- undergraduates, graduate students and post-doctoral fellows -- working in highly-collaborative groups, constantly teaching and learning from one another. Now, as a fifth-year MD/PhD student well into my research years, I can say that science is much more about teamwork (and much less about single-handedly chasing one Nobel Prize-worthy discovery) than I ever expected. I've also found that, because lab groups spend so much time together, they often start to feel like your second home.

For me, finding a lab to call "home" was both the most important and the most difficult part of my graduate training to date. Initially, I came to Stanford to study microglia in the laboratory of the late Ben Barres, MD, PhD, who was my research mentor briefly before he passed away in late 2017 due to pancreatic cancer.

Ben was an incredible scientist and mentor who left behind a vast legacy here at Stanford and within the scientific community at large. After he passed, I looked to Ben's own advice, which he had published in a perspective piece in 2013, as I tried to figure out where I would finish my own graduate training. With his words in hand, these are some of the factors I found most important to my search:

Do your homework. There's no substitute for doing a bit of digging about a lab group before you commit to spending three or more years there. For instance, you'll definitely want to look into whether a lab has grant funding to support you; how often it publishes what you feel are interesting, high-quality papers; and if past members of the lab have gone on to successful careers in academia, industry or wherever you'd like to end up. Remember: you can learn a lot with some thorough googling and by scouring a lab's website!

Publishing matters, but it doesn't have to cost you your humanity. Every lab has its own culture, priorities and general way of getting things done. In particular, some lab groups are laser-focused on publishing many high-impact papers. For people who thrive in a fast-paced, high-stakes environment, joining this kind of lab can be a great way to jump-start their career. For others, being in a lab that moves at light speed can create feelings of being left behind. This can be particularly stressful for trainees, who may worry (as I often did) about keeping up with more experienced lab mates without working unreasonable hours. Personally, I gravitated towards groups that struck a balance between publishing high-quality work and affording lab members the time to learn new skills, make mistakes and get a healthy amount of sleep.

"Team spirit" isn't just for high school pep rallies. As I rotated through different labs, one of the first things I routinely noticed was how much the people around me were enjoying themselves. Science is a team sport, and when I could tell that my lab mates found their projects invigorating, I found myself feeding off their energy in ways that made me happier and more productive. In high-energy labs, I also found that people were much more willing to help one another, which usually made our science better and was always a sign of strong mentorship.

It might sound a bit cheesy, but this kind of "team spirit" was much more important to me than a lab's specific area of study. In Ben's words: "[I]f you like solving puzzles, as all scientists do, there will be many different puzzles that you will find equally rewarding to work on."

Ultimately, these tips happily led me to the lab groups of Kara Davis, DO, and Garry Nolan, PhD. I'll be spending the next few years with them, studying pediatric acute myeloid leukemia in a supportive, exciting learning environment.

It feels good to be home!

Stanford Medicine Unplugged is a forum for students to chronicle their experiences in medical school. The student-penned entries appear on Scope once a week during the academic year; the entire blog series can be found in the Stanford Medicine Unplugged category.

Tim Keyes is an MD/PhD student in Stanford's Medical Scientist Training Program. He likes microglia, snowmobiles, pop music written for teenage girls, and going on terrible first dates.

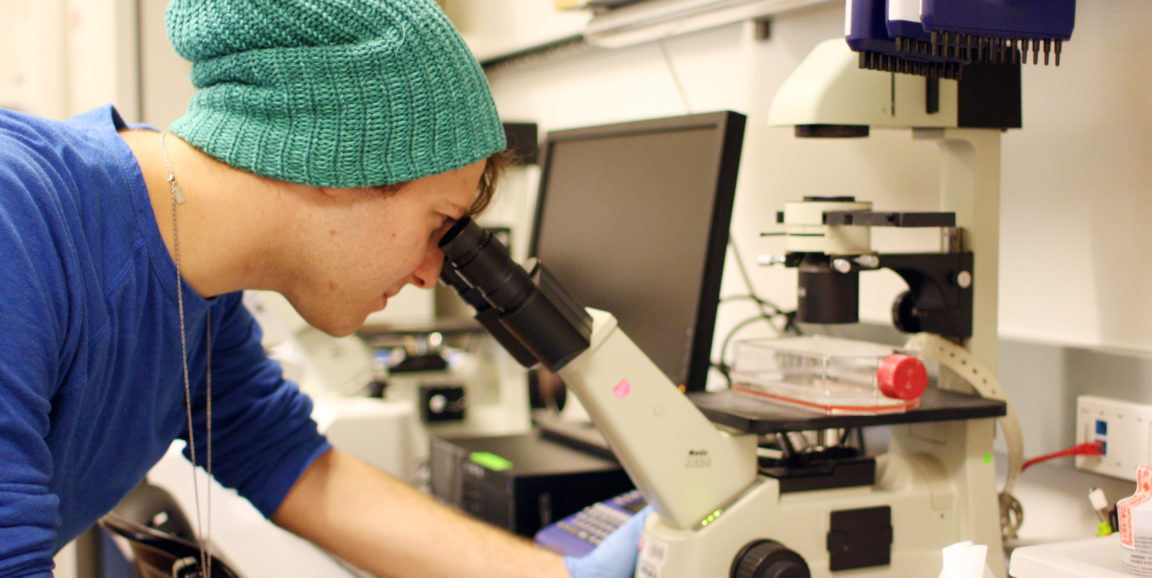

Photo of Tim Keyes by Lyrissa Roman