I wrote a news release a couple of years ago about a study that, as it turns out, has substantial relevance today. The study described a synthetic substance with the ability to dramatically improve breathing capacity in the damaged lungs of rats.

Devised by Stanford bioengineering professor Annelise Barron, PhD, that substance, which has not yet been tested in large-animal studies or, for that matter, human studies, could possibly help patients breathe easier on mechanical ventilators -- or, perhaps, without them.

Her project has gained a new urgency now that tens of thousands of patients with COVID-19 have been put on ventilators in an effort to save their lives.

Ventilators are vital because they help patients breathe when they can no longer do so on their own; however, mechanical ventilation also comes with well-known risks, including infection and lung damage from over-inflation.

Barron's surfactant has the potential to mitigate these risks.

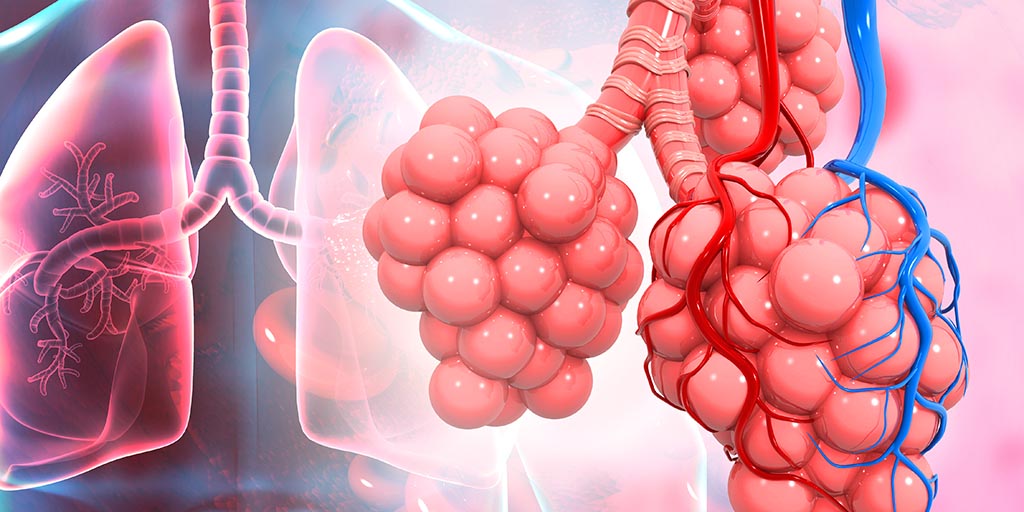

The surface of our lungs is covered with tiny, air-filled tissue bubbles called alveoli. There are about 500 million of them in a pair of healthy lungs. Each is just one cell thick, and each is surrounded by tiny blood vessels gripping it like a hand grips a baseball.

That one-cell-thick, bubbly contour makes the lungs' total surface area huge. This is ideal for gas exchange, the lungs' main function, but also makes the organ among the most fragile of our tissues, Barron told me recently.

"It doesn't take much pressure to burst a one-cell-thick balloon," she said.

Our bodies lessen this pressure by producing a thin coating of a soaplike film, or surfactant, that lowers the tension of the lung's inner surface. This reduces the amount of force required to inhale. Without this surfactant, you couldn't breathe.

Healthy lungs generate the surfactant by themselves. But among the cells in our bodies that SARS-CoV-2 attacks most viciously are the very lung cells, Type II alveolar cells, that produce the natural surfactant.

Application of a synthetic surfactant to breathing-impaired lungs prior to intubation could lower the pressure required for ventilation, Barron said.

In conjunction with an oxygen-enriched environment, she said, that might in some cases help a patient regain the ability to breath independently sooner without sustaining alveolar damage from the ventilator.

She is not currently testing the synthetic surfactant in clinical trials for COVID-19 patients, but is open to the prospect, which she estimates could be achieved within nine months or less if large-animal studies were to get underway soon.

Given the possibility that COVID-19 will be with us for the foreseeable future, that could be a step worth taking.

Illustration of lungs and alveoli by Rasi