Ocular melanoma is the most common form of eye cancer in adults. Though it's relatively rare, if left untreated, it can be lethal, spreading to other parts of the body. There are currently two main ways of treating this eye cancer. The preferred method is radiation therapy, which targets the tumor and can preserve some vision. A second method is enucleation-- removal of the eye.

Prithvi Mruthyunjaya, MD, an associate professor of ophthalmology at Stanford Medicine, and Darius Moshfeghi, MD, a professor of ophthalmology at Stanford Medicine, set out to investigate whether there was any pattern linking patients' racial, ethnic or socioeconomic status with which treatment they received and how long they lived after diagnosis. His team's work was recently published in JAMA Ophthalmology.

I recently caught up with Mruthyunjaya to learn more.

Why did you decide to look into potential racial and socioeconomic disparities in ophthalmology care?

Physicians want to do what is right for each individual patient and not be influenced by a patient's race, sex or socioeconomic status. Particularly in life-threatening conditions like cancer, with promising new therapies that may be considered more risky or expensive, we should not expect to find differences in treatments based on these non-medical factors. Identifying these differences provides opportunities to better understand why they may occur and how to eliminate them altogether.

This is an important issue across all medicine. We previously looked at the same question in retinoblastoma -- an eye cancer beginning in the retina that commonly affects young children -- and did find that there were some differences. Children undergoing enucleation were more likely to be older, non-white or Hispanic, and of a lower socioeconomic status. This observation was not influenced by factors, such as stage of the disease at presentation.

What does it mean to a patient to have a primary enucleation rather than radiation treatment?

Removal of the eye, though it can be curative of ocular cancer, can be emotionally and psychologically difficult for some of our patients. Often, these are eyes that may not have good visual potential, but there is likely some visual function that will be lost.

We can't replace the eye with anything that is functional for vision, so this can affect a patient's depth perception and ability to navigate their daily lives -- and in some cases their livelihoods as well.

Over the past 20 to 30 years, the treatment preference has favored radiation because major studies have shown that there is no survival difference. So we try to save as many eyes as we can.

What did your study find?

This study used a national database that combines a sampling of patient cancer cases from major institutions across the country. We looked at patients with ocular melanoma from 2004 to 2014.

We found that nationally there is a growing trend towards using radiation treatment, rather than enucleation. We also found that non-whites had an increased risk of undergoing eye removal compared to non Hispanic whites; and patients in a lower socioeconomic status had a nearly two-fold increased risk compared to the upper socioeconomic status group. Clinical features, such as the marker of the size of the cancer, did not play a factor in these findings. We also found that the mortality related to the melanoma itself was not impacted, however, by the socioeconomic status or the race of the patient.

These findings tell us that there are features within the decision-making process, the evaluation process and the treatment execution that are fundamentally impacting the way patients with ocular melanoma that are non-white and in lower socioeconomic statuses are being treated.

What are some possible reasons for the disparities that you discovered?

We still do not have a true understanding of why these disparities are present. One hypothesis is that physicians find it difficult to balance what is feasible with the standard of care when a patient is a lower socioeconomic status. Other potential factors include distance from centers offering eye-sparing treatments and geographic variation in treatment patterns.

It is also possible that physicians are altering what they say about the most appropriate treatment option, either overtly or unknowingly, based on non-medical factors such as race or socioeconomic status. Another possibility is that patients feel eye removal is the easier or better option because their options have not been communicated well.

How can this study inform the clinical work of ophthalmologists going forward?

Awareness of these disparities is essential for ocular oncologists and ophthalmologists, as we are the ones who typically see these patients first and perform their definitive treatment.

It is important for patients and their families to have access to all information regarding treatment options. It is also important for physicians to take the time to better explain the consequences of the treatments, including risks, benefits and psychological implications.

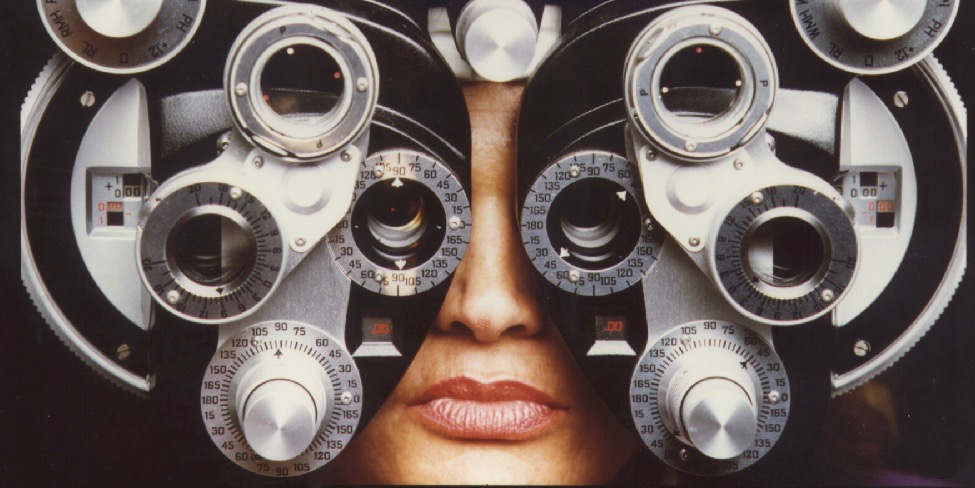

Photo courtesy of the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health