Levels of a substance in nonagenerians' and centenarians' blood accurately predict how much longer they're going to live. The substance comes from the brain.

The findings, in a study published in Nature Aging, could prove useful in developing life-extending drugs. They also raise questions about the brain's role in aging and longevity.

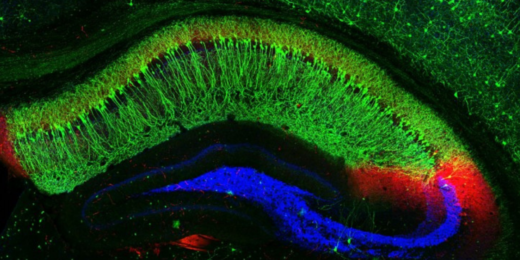

The study, conducted by Stanford investigators including neuroscientist Tony Wyss-Coray, PhD, in collaboration with researchers in Denmark and Germany, zeroed in on a substance whose technical name is neurofilament light chain (abbreviated NfL). A structural protein produced in the brain, NfL is found in trace amounts in cerebrospinal fluids and blood, where it's an indicator of damage to long extensions of nerve cells called axons.

Axons convey signals from one nerve cell to the next and are critical to all brain function. You'd rather they remain intact.

Too much NfL (different from the NFL)

High NfL levels in the blood have previously been associated with Alzheimer's disease, multiple sclerosis, Huntington's disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Lou Gehrig's disease) and other neurological disorders. But the people monitored in the new study were generally pretty healthy for their age.

The researchers first looked at 122 people whose ages ranged from 21 to 107, and found increasing blood levels of NfL -- as well as increasing variation among individuals -- with increasing age.

Next, the scientists followed the fates of 135 people age 100 or over for a four-year period. Most of those centenarians were in good shape to begin with, as shown by their performance on standard tests of mental ability and by a measure of their capacity to meet the routine demands of daily living.

Not unexpectedly, those whose mental tests indicated impairment had more NfL in their blood than those with the sharpest minds did. And those with low levels were substantially likelier to live longer than those with high levels.

A look at people in their 90s confirmed the findings in the over-100 group. Blood NfL levels among 180 93-year-olds not only predicted the duration of these folks' survival, but did so better than mental or daily-coping test scores did.

The investigators showed that mice's blood NfL levels, too, increase with age. But cutting their caloric intake, beginning in young adulthood -- already known to prolong the lives of mice and numerous other species -- chopped the little creatures' blood levels of this substance in half in old age. (This new finding doesn't prove that lowering NfL blood levels causes increased longevity, but it's consistent with it.)

Tie to life expectancy?

At a minimum, NfL appears to accurately flag mortality's approach. That means it might be possible to monitor it as a surrogate marker for remaining life expectancy, much as blood cholesterol levels are used as proxies for cardiovascular health. If so, it could someday help drug developers assess life-extending interventions' efficacy.

Clinical trials of interventions believed to enhance longevity have been impractical, because it would almost certainly take so long to get a statistically significant result that such trials would be hugely expensive -- a major hang-up for pharmas considering investment in longevity drugs. But monitoring a proxy such as NfL could cut years off of such trials' duration, perhaps encouraging drug developers to dive into the clinical arena with life-prolonging pharmacological candidates.

Possibly most intriguing of all: The new findings hint that maintaining a healthy brain in old age is the best route to a long life.

"It will be interesting to see how and why the brain might be so important in counting down our final years and months," Wyss-Coray told me.

Photo by Pablo Bendandi