Early 20th century celebrity criminal Willie Sutton was asked why he robbed banks. He is said to have answered, "Because that's where the money is."

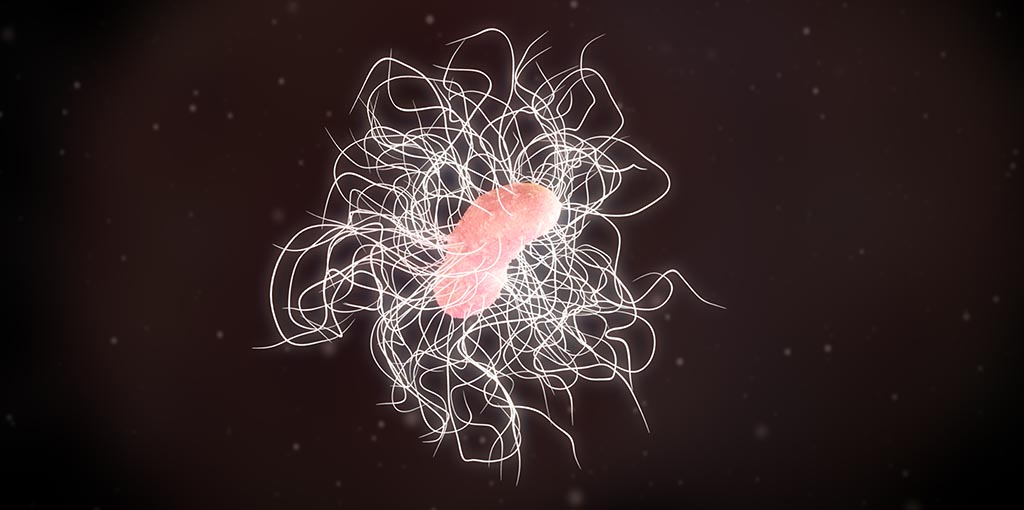

Now, new research tells us the answer you'd get when you pose a similar question to Clostridioides difficile, a gut-dwelling bacterial species that, when it runs amok, causes 450,000 infections and 15,000 deaths in the United States each year.

C. difficile, commonly called C. diff, inhabits about 30% of all people's intestinal tracts, typically dwelling quiescently at trace levels in our ecosystems, which abound with hundreds of bacterial species. "It scrapes by on scraps of whatever nutrients come along," Stanford Medicine microbiologist and gut-bacteria sleuth Justin Sonnenburg, PhD, told me.

But a Jekyll-and-Hyde twist tripped off, for instance, by a course of broad-spectrum antibiotics that wipes out a substantial portion of the competition can launch C. diff on a conquest in which it starts pumping out bulk quantities of toxins.

That makes the gut a target for diverse inflammatory immune cells bent on punching out every microorganism they come across there. The collateral destruction can include severe tissue damage, leaving a person bedridden with abdominal cramps and diarrhea for weeks, or worse.

C. diff views hospitals, of all places, as particularly hospitable. That's because there are a lot of people on antibiotics regimens there, for one thing. For another, hospitalized patients, especially elderly ones, tend to have relatively weakened immune systems.

A third factor: C. diff spores stick to walls and other surfaces, Sonnenburg told me.

Once having established a foothold in a building, this bug is tough to get rid of. It can run rampant in hospitals and other large health care settings, such as nursing homes. (A 2015 study by the CDC says that 1 of every 11 patients age 65 and older with health-care associated C. diff infection died within 30 days of diagnosis.)

Like most living creatures, a bacterium is driven by the evolutionary imperative to eat, grow and multiply. Organisms that do this, thrive. Those that don't, die out. If you're a gut-dwelling microbe, disabling or even killing your host doesn't seem to be a good way to keep the ball rolling.

So, in a study published in Nature, Sonnenburg posed a Suttonesque question: "Why does this bug cause inflammation? What's in it for the bug?" Why, of all things, would C. diff want to rile up an army of angry immune cells?

Not-so-sweet sorbitol

To find out, he and former graduate student Kali Pruss, PhD (now a postdoc at Washington University), made a mutant version of C. diff that's identical to the natural one except it doesn't produce toxins, so it doesn't cause any gut inflammation. They infected special mice -- raised in hyper-hygienic quarters so their guts were germ-free -- with either the toxin-producing or toxin-lacking version, and waited to see what would happen.

Their experiments implicated our own immune cells as the as an answer to their question: Because that's where the sorbitol is.

Sorbitol is a so-called sugar alcohol commercially used as a food additive, said Sonnenburg, who at one point in his career was trained as a sugar biochemist. Although it has a sweet taste, it's considered non-caloric because we humans are short on the enzymes needed to metabolize it efficiently. So we extract less energy from it than we would from the sucrose for which it's a substitute. If you check the ingredients on a bottle of diet soda or pack of sugarless gum, for instance, you may find sorbitol listed.

It turns out that sorbitol is one of C. diff's favorite foods. It's got the enzymes it needs, the study showed, to get the full caloric benefits of sorbitol -- enzymes it makes more of whenever it senses sorbitol in its surroundings.

Our own bodies, although they don't digest sorbitol well, can produce it, albeit not usually in gigantic amounts. Curiously, the study showed, the cells in our bodies that are best equipped to make lots of sorbitol are immune cells in an angry mood -- the very cells preferentially recruited to the gut by C. diff's toxin tantrums.

How to block sorbitol's takeover?

Nobody really knows what the immune cells do with the sorbitol they're making, but they don't consume it. (Maybe sorbitol plays some as yet unknown regulatory role in immune response?) But no matter. Put them in an inflammatory mood, and they'll generate a glut of sorbitol.

That's just fine with C. diff. Its toxins trigger a twofer: plenty of sorbitol for it to pig out on, plus the wholesale wipeout of a bunch of benign bugs with whom C. diff had erstwhile been forced to share food.

"That puts C. diff in the driver's seat," Sonnenburg said. A full-blown C. diff bloom in the gut can boost its abundance to 50% of the gut-resident bacterial population, sustaining a vicious circle of toxins, further inflammation, immune cells serving up sorbitol while killing off the competition, further C. diff population expansion, and around and around we go.

The findings could open the door to new ways of blocking that takeover, Sonnenburg said. Plus, they raise an exciting, unexpected question. "You see amped-up sorbitol production in our immune response to any inflamed-gut induction," he said. "Why is it being produced at all? What makes sorbitol so reliably part of immune response that C. diff can confidently bet its life on it?"

Maybe a few years of hard time in a petri dish will get the bug to spill its secrets.

Image by gaetan