The Stanford Health Care Clinical Virology Laboratory was a bustling place even before the COVID-19 pandemic. But the intensity has been palpable since its medical director, Benjamin Pinsky, MD, PhD, designed what would be one of the first tests for COVID-19 status to receive FDA emergency use authorization for clinical testing in the United States.

The lab has since conducted more than 600,000 such tests to date -- until recently, one out of every 20 COVID tests performed in the state of California.

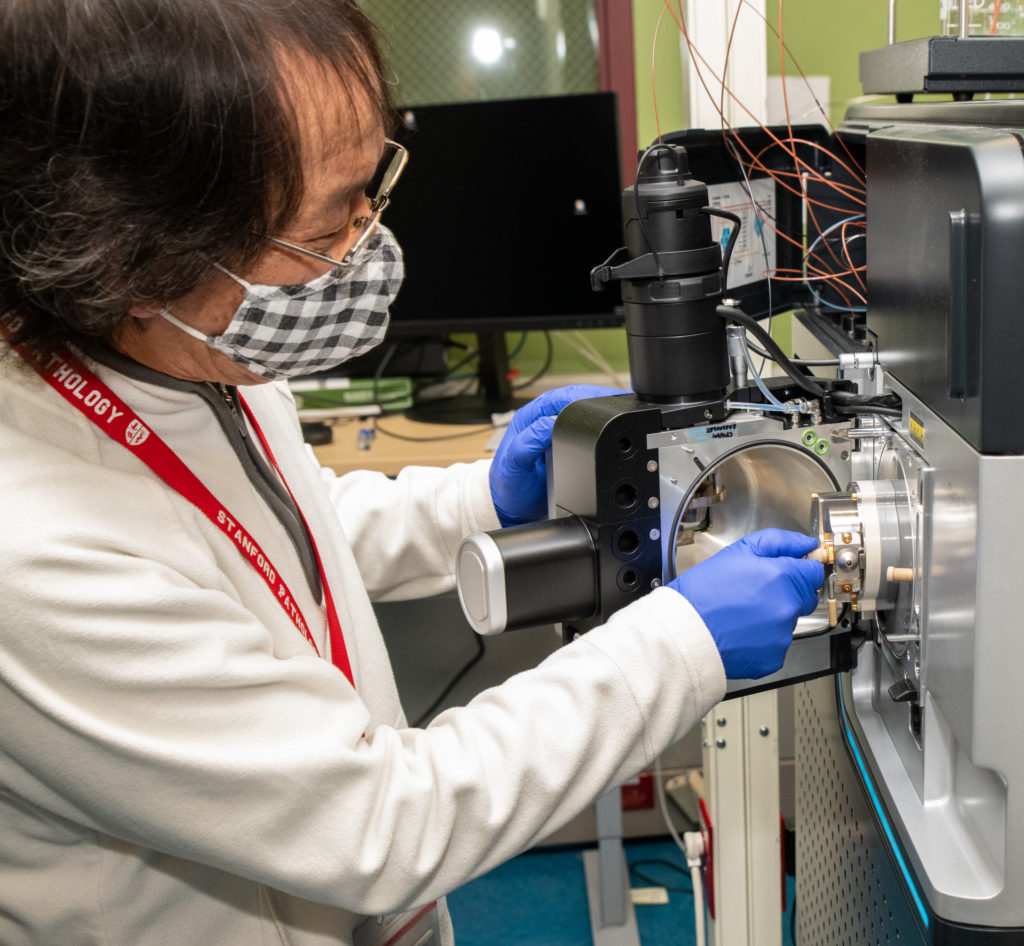

Obadia Mfuh Kenji -- his colleagues call him Kenji -- joined the lab just after the pandemic's first surge in May 2020. He left a comfy job at a biotech company to supervise the lab, and has since been promoted to manager of infectious diseases and esoteric testing.

"He's the brave soul who walked in to become a virology laboratory supervisor in the middle of a COVID pandemic," said Christina Kong, MD, a professor of pathology and vice chair of clinical affairs for pathology, who directs Stanford Health Care's clinical and anatomic pathology labs.

"No matter what happens, Kenji always stays calm and always has a smile on his face," said Kong.

Kenji, PhD, is often in the lab for 12-hour stretches. And he's always on call. "When I get home, I continue working -- because biology is 24/7," he said. "My phone is always ringing. I sleep with it beside my pillow. That's my life even on weekends."

Which brings us to two mysteries concerning Kenji: Why did he leave that relatively relaxed biotech job to come to Stanford Medicine? And how does he maintain his extreme unflappability? The seeds of both were planted during his years growing up in Cameroon as a son of a minister.

Dropped into turmoil

It's easy to see why Stanford's clinical virology lab would want to hire Kenji. He has a PhD in infectious diseases and a master's in public health. Along with that hefty background, he had hands-on experience in state-of-the-art gene-sequencing technology. He was a lead scientist for clinical genomics at Illumina, a Bay Area biotechnology company.

"He could be a medical director of a lab in his own right," Kong said. "We typically lose people to industry. Kenji walked in the opposite direction."

Coming to Stanford fulfilled a dream he'd had as a student in Cameroon: "My wish had always been to attend Stanford," he said. "My dad didn't have a credit card to pay for my application." So he took the long way around. After obtaining a bachelor's in medical laboratory sciences in Cameroon, he earned a master of public health degree in Manchester, England, and then a doctorate in biomedical sciences at the University of Hawaii before going to work at Illumina.

But the chance to work with Pinsky was another major draw, he explained.

"I saw an opportunity to work with the highest level of researcher," said Kenji. "And I saw an opportunity to go back to what I'd studied: infectious disease."

Pinsky, concerned by reports coming out of China in early January 2020, had quickly implemented a new SARS-CoV-2 test. Two months later, on Feb. 29, the FDA authorized the test for emergency use. By March 4, the lab was offering clinical testing -- and the virus had launched its initial surge.

"Kenji got dropped right into the middle of it," said Pinsky.

"We had to start testing for something we'd never seen before," said Jennifer Fralick, administrative director of laboratory services for Stanford Health Care. "We were bringing in new testing platforms, adding new instruments, adopting new reagents and training new clinical lab scientists."

The pandemic was well underway when Kenji accepted the job, he recalled. "A friend at Illumina said, 'Are you crazy? You won't have a life!' I told him, 'I'm going where the fire is burning. I hope to be in a position to help put it out.' It was the best decision I ever made."

Daily disruptions, never an eruption

As supervisor, Kenji met with Pinsky frequently "to get the wheels on tight," as Pinsky put it. Kenji made sure all testing was done correctly, that all the instruments were running smoothly and everybody knew how to use them, and that all testing was in compliance with licensing agencies.

As manager, he meets with Pinsky and Fralick weekly to discuss implementation of COVID-19 variant testing, while continuing to perform all the duties of virology lab supervisor pending the hiring of his replacement.

But that's routine. "On a daily basis, there's an emergency," said Pinsky. "There's always some crisis: An instrument goes down, we run out of a reagent, whatever. Kenji is called upon to deal with those problems."

He also deals with the unexpected. "You're going to have problems you've never had before," said Kenji.

In response to the pandemic, the laboratory's workforce has grown from about 25 to about 63 since Kenji arrived.

"In November, the lab underwent an expansion: New hires, new instruments, new tests, and more space to accommodate them all," Fralick said. A room full of freezers was cleared out and the freezers were replaced with an automated testing line. "We increased the lab's space from 3,600 to 4,600 square feet."

Kenji coordinated everything, accomplishing the buildout in record time. A transformation that would normally take a year took a month. Kenji validated each of the 17 new testing instruments to prove they worked as they should.

"We were able to ramp up our testing capacity from 2,000 to 6,000 tests a day," Fralick said.

New strains, new stresses

The emergence of several new viral strains has spurred enhanced tracking efforts: All positive COVID-19 samples are run through a fast screening test to look for specific variants.

Every sample showing evidence of a variant undergoes a slower, more fastidious confirmation process involving whole-genome sequencing, which can take three days.

Another test was pioneered in Pinsky's lab to determine whether a COVID-19-positive sample contains active virus or mere residual remnants of a cleared infection.

Each new test poses a new challenge, because every test Pinsky and his team designs means introducing a new testing protocol, instrumentation tweaks and training sessions.

"He's a great leader," Fralick said of Kenji. "He's not afraid to hold people accountable or offer his support. People respect him because of his knowledge."

Early dreams and responsibilities

Knowing he's making an impact helps Kenji maintain his calm competence: "At every moment, I keep in my mind that I'm helping to improve patients' lives."

Kenji also draws on a rich reservoir of life experiences. "When I was young, my father was assassinated. In Africa, if your father dies and you're the oldest son, you have to take on responsibility for your family. That's no small task. So when something tough gets thrown at me now, I can always say, 'I've seen worse.'"

His faith helps too. "Every day I pray to God to give me the strength to face that day," he said. "The Bible says God doesn't give you a load that you can't carry."

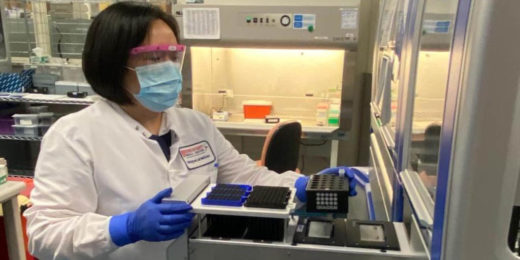

Top photo by Steve Fisch of Obadia Mfuh Kenji, manager of infectious diseases and esoteric testing at Stanford's clinical virology lab, with Naomi Iwai, a clinical lab scientist.

Related: ABC7 News aired a segment on the role faith plays in Kenji's life and work, which can be viewed here.