Stanford researchers have discovered that the level of certain proteins in the eye could predict survival risk in patients with uveal melanoma, a relatively rare but deadly form of adult eye cancer. The researchers hope the discovery will not only aid in disease monitoring but could also lead to therapies tailored to individual patients.

For a recently published study on the finding, Prithvi Mruthyunjaya, MD, and Vinit Mahajan, MD, PhD, associate professors of ophthalmology at the Byers Eye Institute at Stanford, led a research team that surveyed 1,000 proteins in more than 30 Stanford Medicine patients with uveal melanoma. They then analyzed proteins in the patients' eye fluids to discover key protein biomarkers, or molecular signals, linked to potentially metastatic disease, meaning it spreads to other parts of the body.

According to their study, published Feb. 24 in Molecular Cancer, a minimally invasive liquid biopsy method of examining the cancer proteins revealed critical diagnostic information and could provide ongoing monitoring of the cancer to determine the chances it will spread. Mruthyunjaya and Mahajan shared senior authorship.

I recently spoke with Mruthyunjaya and Mahajan to learn more about the research.

How does uveal melanoma metastasize in patients?

Mruthyunjaya: Uveal melanoma starts in and grows from the inner layer of the eye called the uveal tract. Tumors of this variety are typically only millimeters in size, but they can become big enough to compromise the patient's vision. Through treatments, including radiation in the eye or eye removal surgery, we can control the cancer in more than 95% of cases.

But these cancers have a nearly 50% chance of spreading to other parts of the body in untreated cases. Through mutations, the tumor cells can enter the blood stream and grow in the liver, which happens 80% of the time, or in the lung, which happens about 10% of the time.

Why is this research important?

Mruthyunjaya: Uveal melanoma afflicts 6 in 1 million people in the United States and approximately 2,500 new cases are identified annually.

In our clinical trials at Stanford, we've made significant advances in understanding the genetics of the disease; we can accurately predict the risk of metastasis of a patient through a complex examination of the eye tissue. But we do not have any laboratory tests we can order to confirm that metastatic cells have left the eyeball.

Also, there are no U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved treatments. This type of eye cancer is biologically and genetically different than skin melanoma, so treatments used for metastatic skin melanoma are not successful against it.

Accurately identifying signals that are released near the tumor can help guide accurate diagnosis, identify the disease at the earliest stage, and, most importantly, lead to customized treatments.

Why did you zero in on proteins and their function in the eye?

Mahajan: Proteins give us a real-time, dynamic story about what is happening in the eye in a way that genetics cannot. Because there are limited diagnostic, therapeutic, and monitoring options for the disease, our goal was to discover key protein biomarkers, or molecular signals, linked to this cancer.

We zeroed in on proteins in eye fluid near the tumor because they could give us a broad picture of what was happening in and around the tumor. By casting a wide net, we gained insight into both common and rare molecular changes that could inform highly personalized medicine -- something that could help care for rare and hard-to-treat eye diseases.

Currently, surgeons biopsy the tumor to study its DNA activity, but our approach takes a small sample of a gel-like substance called vitreous from inside the eye near the tumor, which is less invasive.

How are the tissues collected and how will your findings lead to better eye disease treatment?

Mahajan: We bring a mobile laboratory bench into the operating room during patient surgeries, which allows us to immediately process the fluids for advanced molecular analyses. It takes less than ten minutes. Clinical and tumor information is entered into an online database, then the fluid is frozen and stored in our Ophthalmology Biorepository.

For the study, this seamless set up allowed us to immediately process and save fluids and other eye tissues collected in the operating room that would otherwise rapidly degrade. Since most drugs target proteins, knowing the exact protein profile for each patient will help inform how to develop innovative therapeutics and diagnostics.

Mruthyunjaya: We anticipate that fluid biopsies from the eye may supplement or replace the need for direct tumor biopsies by providing a potentially safer and more easily repeatable method to determine risk of metastasis in our patients.

What's next for this research?

Mahajan: We are working to validate these findings in other patients, as well as determine the protein changes that occur in the fluid in the front of the eye and in the blood. We also want to follow these changes over time. Furthermore, we are working with the Division of Oncology at Stanford to develop clinical trials for patient-specific chemotherapy to prevent the disease.

Solutions depend on patient engagement and surgeons working together with scientists.

Author Kathryn Sill is a communications professional in the Stanford Medicine Department of Ophthalmology.

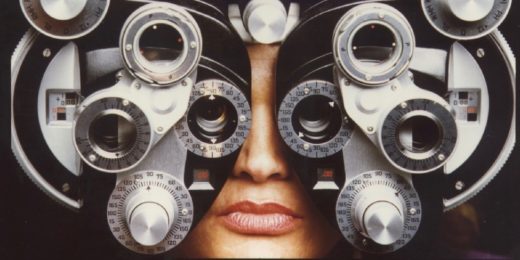

Top photo, courtesy of Stanford Health Care, of Prithvi Mruthyunjaya, MD, holding a 20 diopter condensing lens, a tool used to focus light from the ophthalmoscope to obtain an image of the retina.