Since 1999, more than 600,000 people in the United States and Canada have died of an opioid overdose. And that number is expected to rise -- dramatically. It's projected that without new efforts to stem the crisis, opioid deaths during this decade will reach 1.22 million in the U.S.

These startling statistics are part of a new report issued by Stanford Medicine and The Lancet. The report shines a spotlight an enormous problem in both Canada and the United States: inadequate policies governing opioid sales and use.

"Unrestrained profit-seeking and regulatory failure instigated the opioid crisis 25 years ago, and since then, little has been done to stop it," professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences Keith Humphreys, PhD, said in a Stanford Medicine press release. Humphreys chairs a commission of 17 health experts from the United States and Canada that produced the report.

Opioid-induced deaths and addiction have been compounded by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, robbing people of daily structure, recovery programs and social connection -- all crucial elements of recovering from addiction, according to Humphreys.

Anonymous addiction

Alongside detailed statistics and policy recommendations for curbing opioid use, the report includes anonymous voices of people and families who have struggled with opioid addiction, grounding the enormity and often unwieldy nature of the opioid crisis in raw, first-person reflection.

One patient recovering from alcohol use disorder who became addicted to morphine describes the struggle: "I've got terrible pain, but I'm also addicted to painkillers, and right now my addiction is worse than my pain."

Another patient who became addicted to prescribed meperidine, a type of narcotic, discusses how the addiction worsened.

"After the surgeries, when I got back home ... I was lost. I was in a different world, on deep, deep, deep medications, different types. And then I started finding myself calling more, and then at some point your mind turns to the only thing that really makes any difference [which] is to get pain medication," the patient reported. "It was kind of an irrational thing, that this is supposed to help me get up and move around, but it's keeping me down and destroying me."

One person describes their introduction to addiction:

"I started seeing a lot of pills around 15 years old and I told myself I was never going to do them. But kids were selling Oxys at school for $3 a pill. By the time I was 19, I was looking in every medicine cabinet and bathroom."

Often addiction is painted as a moral failing rather than a health problem, Humphreys said. "Yes, this is an illness. Yes, it is treatable. And yes, you have a chance to recover."

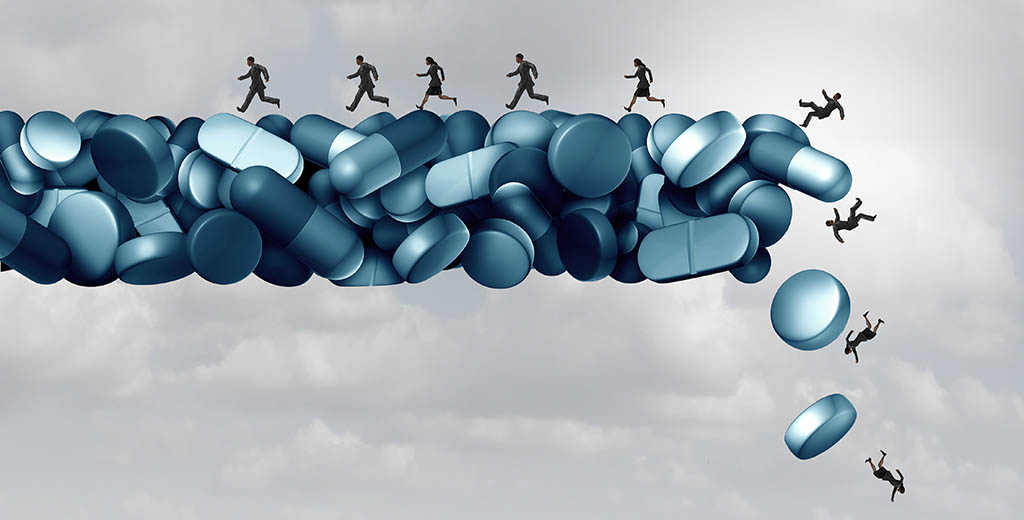

Photo by freshidea