Historically, cancer treatment was trial-and-error, as physicians zapped and sliced tumors with all the tools they had available. Now, however, cancer treatment is increasingly becoming precise and personalized.

To wit: A team of Stanford researchers has developed an imaging agent that can identify whether a particular lung cancer drug is likely to work for an individual patient.

This agent, a tracer, binds to a mutation in the tumor cells that is targeted by a widely used drug. It emits signals visible in a PET scan. If the patient doesn't have the mutation, the drug doesn't work, and the new tracer would allow clinicians to quickly figure that out before administering therapy.

The research appears in Science Translational Medicine.

As described in our news release:

'Some people wonder, ‘Can’t you just prescribe the drug and wait to see if the tumor shrinks? If it shrinks, then you know it’s working,' said Sanjiv "Sam" Gambhir, MD, PhD, professor and chair of radiology at Stanford.

While in broad strokes that’s true, there’s a flaw to that approach: If the therapy isn’t effective, the tumors will not only continue to grow, but continue to become more molecularly complex. 'In the time you waited to see if the tumors shrank, those tumors continued to evolve, and that makes it more difficult to treat with the next round of therapy,' Gambhir said.

The tracer has been tested in a small clinical trial, but a larger trial — in China — is planned before the compound is more broadly available, Gambhir, who was co-senior author of this paper, said.

There's an ever-present need for new, specialized imaging agents, he added:

There are hundreds of drugs, just like there are hundreds of imaging agents; we have to keep building new ones for different purposes... We have to keep looking for different ways to interrogate the underlying biology of the tumor, and the new method we’ve developed goes after actually measuring mutations in the tumor.

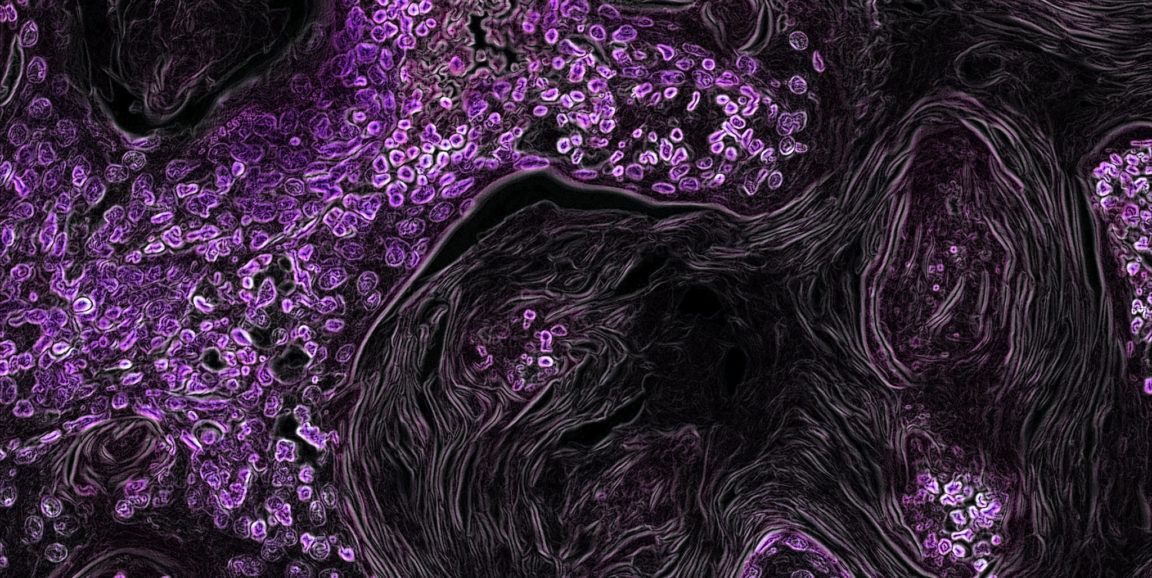

Image by National Cancer Institute, NIH