Serial health technology entrepreneur Josh Makower, MD, provided a behind-the-scenes look at the innovation process at a recent Stanford Biodesign event.

He was speaking to a familiar audience: along with Paul Yock, MD, Makower co-founded the Stanford Byers Center for Biodesign, and is a chief architect of the need-based process for health technology innovation that is the core of its training program.

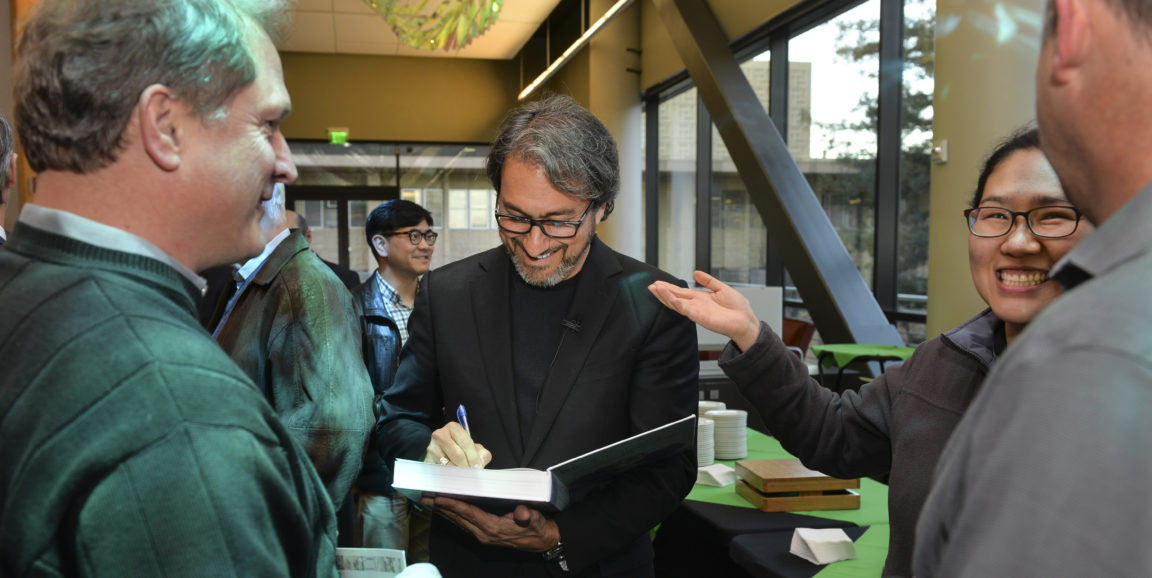

The first step in the process is to identify and thoroughly understand an important health care problem, explained Makower, who is shown signing a copy of Biodesign: The Process of Innovating Medical Technologies, above. Among other pursuits, Makower leads a medical device incubator that has brought eight new technologies to patients in clinical areas ranging from sinusitis to prostate disease.

“When deciding what to work on, one of the things we look for is a clinical area or procedure where the technology has been essentially the same for decades,” Makower said. “You’ve got to make advances that improve outcomes and/or reduce costs.”

Another clue: a significant discrepancy between the number of procedures done annually, and the number of people who could potentially benefit from the intervention. “The disconnect suggests that outcomes aren’t optimal, or the procedure has significant side effects, or there’s a large group of patients who don’t have access to the procedure or don't qualify for it,” Makower said.

Sometimes personal experience drives the research. Makower’s own chronic sinusitis triggered his interest in developing a less invasive treatment for the condition. Similarly, Ted Lamson, one of Makower’s associates, saw his dad and uncle struggle with benign prostatic hyperplasia, an age-related condition in which the prostate gland enlarges and presses in on the urethra, causing lower urinary tract symptoms.

After identifying several promising clinical needs, Makower pits the needs against one another, setting up a competition. “We chase several needs in parallel, going deep in our research to determine which problem, if solved, will have the greatest impact on patient care and is most likely to be adopted,” he said.

When it is time to start thinking about a solution, Makower said he relies on the patient's perspective to guide the design. “The experience of the people who have the problem and what they want is a significant part of the invention process." He continued:

As physicians and engineers, we tend towards aggressive solutions that often involve removing or destroying tissue. But when you take a more holistic approach based on the feelings of the people you’re trying to help, it forces you down a path that tends to be much more minimally invasive. It tends to be something that is more sensitive to helping the body do what it would want to do on its own.

To illustrate, Makower described watching a surgical procedure as part of his team’s research into chronic sinusitis.

To access the problem area, the surgeon first had to cut out thumb-sized piece of healthy tissue. And while the procedure was successful, the patient was left feeling like he’d been hit in the face with a baseball bat.

[We thought] 'Maybe we can navigate around that tissue with something flexible, and by preserving the anatomy it will be a better experience for the patient.'

Similarly, when developing a minimally invasive device to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia, Makower explained, “The key insight was that the enlarged prostate tissue is benign. So we thought, maybe instead of destroying it, we can just push it out of the way.”

In closing, Makower summarized, "As a physician, it's rewarding to make a positive impact on one patient at at time. By developing technologies that enable changes in the way care is delivered, it's possible to help people on a larger scale."

Photo by Rod Searcey