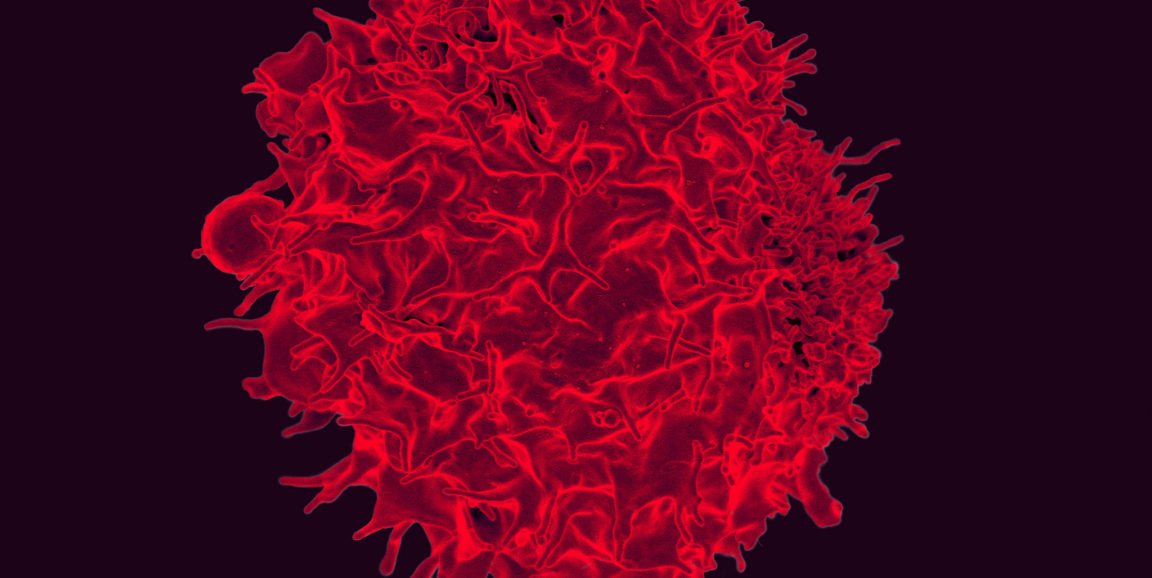

Scientists have made an important step forward in addressing one of the worst human cancers, a brain tumor called diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) that affects school-age kids and has a median survival time of only 10 months. In a new study published today in Nature Medicine, a Stanford team describes how engineered immune cells called CAR-T cells got rid of human DIPG tumors implanted in the brains of mice.

The researchers found that, in about 80 percent of cases, DIPG cells have lots of one specific marker on their surface, a sugar molecule called GD2. The sugar has been observed on other cancers before, but no one realized it was abundant on DIPG.

The research team treated DIPG cells in a dish with T cells that had been engineered to be activated by GD2; the basic idea is the same as that underlying Kymriah, the recently approved T-cell therapy for relapsed pediatric leukemia, although the molecular target is different. In this case, the engineered cells killed DIPG cells in vitro, so the researchers moved on to tests in mice implanted with the human tumor, and again the CAR-T cells were successful.

From our press release:

'I was pleasantly surprised with how well this worked,' said Michelle Monje, MD, PhD, assistant professor of neurology and a senior author of the study. 'We gave CAR-T cells intravenously, and they tracked to the brain and cleared the tumor. It was a dramatically more marked response than I would have anticipated.'

The findings add to a growing body of evidence that CAR-T cells could be useful therapies for solid tumors, which have been regarded as more difficult to treat with this approach than blood cancers. Notably, the mice whose tumors were cleared still had some residual cancer cells, a few dozen per animal, so CAR-T cells are not likely to be a perfect cure; they will probably need to be combined with targeted chemotherapy.

Still, the team is cautiously optimistic about future clinical trials, as our press release explains:

'As a cancer immunotherapist, what gets me really excited is when you take an established tumor and you make it disappear,' said Crystal Mackall, MD, professor of pediatrics and of medicine and the study's other senior author. 'In animal studies, we can often slow the growth of a tumor, shrink a tumor or prevent tumors from forming. But it isn't so often that we take a tumor that's established and eradicate it -- and that's what you want in the clinic.'

However, some mice experienced dangerous levels of brain swelling, a side effect of the immune response triggered by the engineered cells, the researchers said, adding that extreme caution will be needed to introduce the approach in human clinical trials.

Photo by NIAID