Renowned economist Jeffrey Sachs launched an ambitious — some would say audacious — experiment in 2005 in his quest to prove that it is possible to end global poverty by taking a holistic, community-led approach to sustainable development.

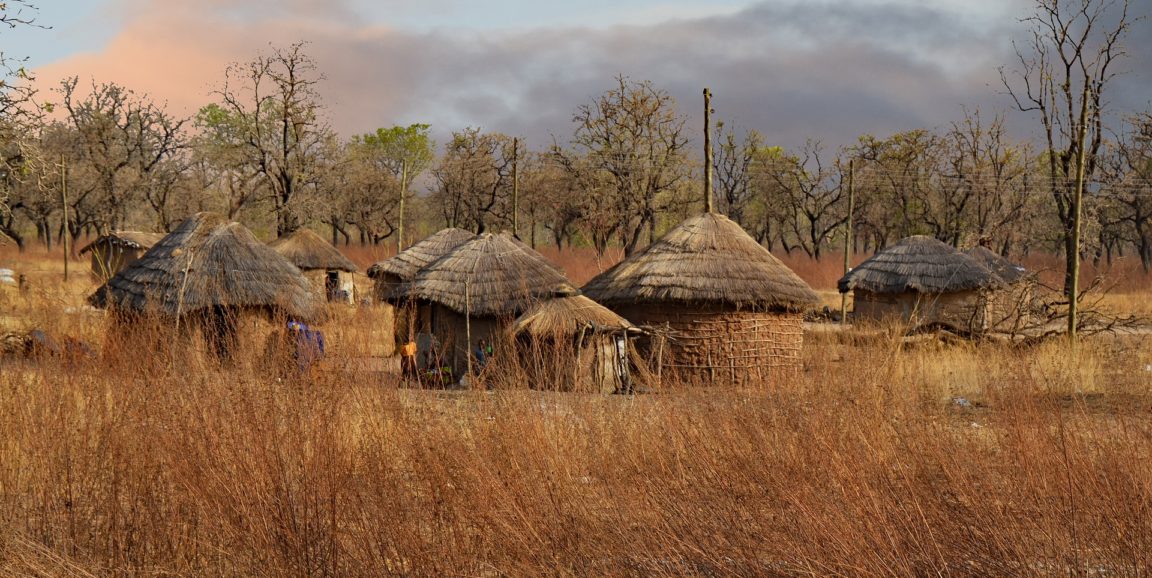

The Millennium Villages Project targeted more than a dozen sub-Saharan villages, using an integrated approach to help these villages achieve the U.N. Millennium Development Goals to address poverty, health, gender equality and disease.

Funded by World Bank loans, governments and private contributions, the pilot project aimed to investigate whether conditions would improve dramatically for the half-million residents of the villages in the 10 project sites by improving access to safe drinking water, primary education, basic health care, and other science-based interventions such as better seeds and fertilizer.

The results are in. And boy are they are mixed.

Some harsh critics say the MVP was a waste of hundreds of millions of dollars, the project was riddled with fundamental methodological errors, and there is little scientific evidence that the project attained its goals.

Others, such as Sachs himself in a perspective in The Lancet Global Health, say that while the outcomes on poverty were mixed and impacts on nutrition and education often inconclusive, “the lessons learned from the MVP are highly pertinent.”

Stanford Health Policy’s Eran Bendavid, MD, who penned a commentary of the project and is featured in a podcast, falls somewhere between critic and advocate.

"The project, set up as a focused set of interventions implementing an important idea in international development about how to best help the poor, was a terrific opportunity for learning about how to reduce poverty and improve well-being,” Bendavid told me in an interview.

But the MVP was not set up as a randomized field trial, nor was there any monitoring of what happened in any comparison areas to make sense of what the intervention had achieved.

“No comparison sites were selected [at the beginning of the study] either. That was a wasted opportunity,” he said. “The endline evaluation of the project does the best that can be done to eke some information from the limited opportunities for learning.”

Bendavid, an associate professor of medicine and an infectious diseases physician who focuses on global health, said the project invested about $120 per person per year for 50,000 people for 10 years. That’s about $600 million.

“The clearest evidence of benefits from this investment is improved maternal health care and health outcomes,” he said.

The authors of the final evaluation found a more positive takeaway from the project.

“We found that impact estimates for 30 of 40 outcomes were significant and favored the project villages,” wrote the authors, including Sachs, of an endline evaluation of the project, which was also published in The Lancet Global Health.

The authors concluded that the project had significant favorable impacts on agriculture, nutrition, education, child health, maternal health, HIV and malaria, and water and sanitation.

In all, a third of the targets of the Millennium Development Goals were met in the project sites, they wrote.

Bendavid said that the endline evaluation “marks an important chapter in our understanding of Africa’s meandering path towards health and economic development.”

He noted that the project’s evaluation, which was done as well as possible given the difficulties of assessing its impact 10 years on, still failed to shed much light on the MVP’s approach as a method to bring an end to poverty.

“This was such an important project,” Bendavid said. “We’ll never fully know where it succeeded and where it did not, but this evaluation is a welcome bookend to what we are likely to ever learn from that experience.”

A version of this piece appeared at Stanford Health Policy.

Photo by lapping