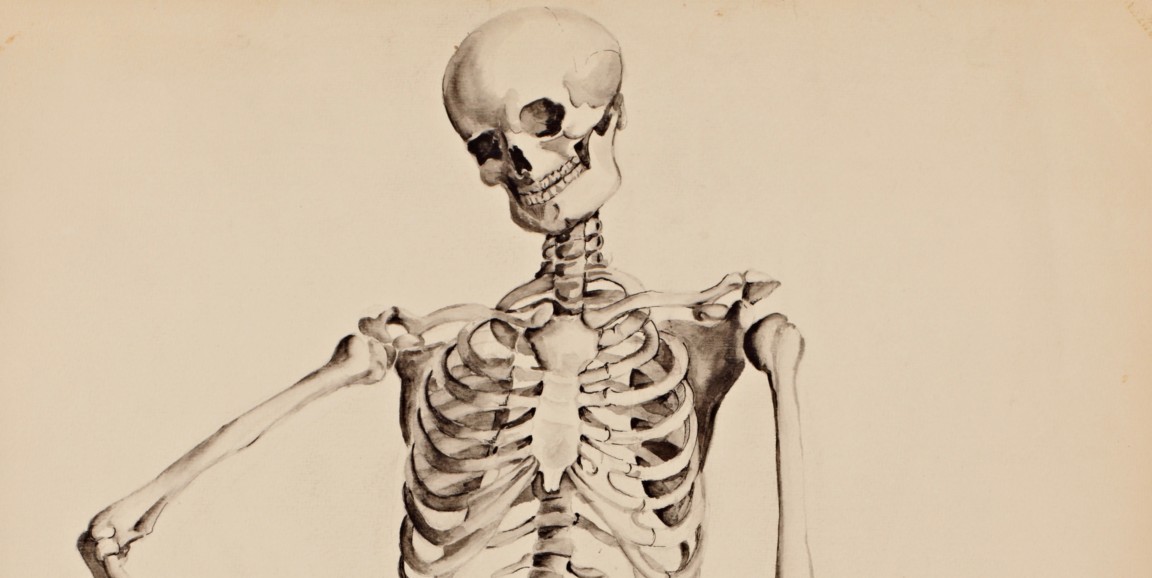

The words "cheeky" and "skeleton" don't typically go together, but they do when describing the signature artwork anchoring the new exhibit at Stanford's Cantor Arts Center.

The graphite and ink drawing by the late Bay Area artist Beth Van Hoesen portrays a grinning skeleton, head tilted and hand perched jauntily on hip as if to say, "I may be dead, but I still look good."

The exhibit, called "Betray the Secret: Humanity in the Age of Frankenstein," is part of Frankenstein@200, a year-long commemoration of the novel's 200th anniversary sponsored by the Stanford Medicine & Muse Program.

Elizabeth Mitchell, PhD, museum curator at the center, whose doctoral work focused on English printmaker and social critic William Hogarth, says the exhibit allowed her to pull together disparate works from the Cantor's collections, including Hogarth, to tell a varied and coherent story about some of the compelling issues raised in Mary Shelly's Frankenstein: Or the Modern Day Prometheus, including defining what is human and how the physical body's interaction with science and technology can change the definition.

She explained:

The second part of the book's title is important, as we reflect on medicine in the digital age, and how medicine, science and ethics meet in the physical place of the body...

The title's reference to Prometheus foreshadows how the Frankenstein character uses technology to disrupt life's natural cycle and 'play God' by creating life artificially in his laboratory. That same criticism of 'playing God' reverberates today in debates over how medical technology affects the body by prolonging life, curing diseases with invasive and experimental treatments, assisting with fertility -- our bodies are where science and ethics meet.

The exhibit tracks the practice of grave digging for bodies as practiced by Victor Frankenstein in the novel, and practiced by medical men, or "resurrection men" over the centuries, as well as the advances and sometimes dark unexpected consequences of laboratory research.

For example, it includes "The Four Stages of Cruelty", a print by William Hogarth that was in part inspired by passage of England's Murder Act of 1751, which mandated that the bodies of murderers executed for their crimes could not be claimed by their families for a traditional Christian burial. As an additional postmortem punishment, the bodies were given to surgeons who used the corpses for anatomical research, Mitchell explained.

The exhibit also includes a satire by Samuel Ireland linking the pioneering Scottish anatomists John and William Hunter to grave robbing. As the brothers examine a corpse laid out on a slab, there is another corpse's head superimposed on a shovel in the lower left of the image.

The Ireland satire is double-hung with a photograph from the 1950s by W. Eugene Smith, an image of surgeons operating in a crude field hospital. The composition and placement of the patient in the Smith photograph echoes the position of the corpse in the Ireland print. The texts in this area emphasize that medical knowledge came from many different kinds of situations, many of them pointing back to shadowy origins that have provoked debate for centuries, Mitchell told me.

"We look at the word galvanized in the context of scientific advancement, and how electricity was the spark in Shelley's time, bringing with it both positive and negative results, as do many scientific and medical advances," Mitchell said. "Electricity was an exciting, engaging technology that was inspiring new medical research in her time; it was a catalyst for new thinking."

Noting that Mary Shelley was only 18 when she penned what is considered the first horror novel, Mitchell says it is uncanny how the young writer's cautionary tale about science without consideration and hubris is still vital today. "Two centuries have passed, but we are still grappling with some of the very same issues."

For example, the introductory text to the exhibit calls out the ethical challenges raised by "drone weapons, artificial intelligence, stem cell research [and] cloning."

Local readers may also be interested in a talk by Mitchell that is free and open to the public:

- "Body Work: Representing Physicians, Surgeons, and Resurrection Men" on May 30th at 2 p.m.

Image by Beth Van Hoesen (U.S.A., 1926-2010), Stanford (Arnautoff Class), 1945. Graphite and ink on paper. Cantor Arts Center collection, Gift of the Estate of Beth Van Hoesen, 2011.62