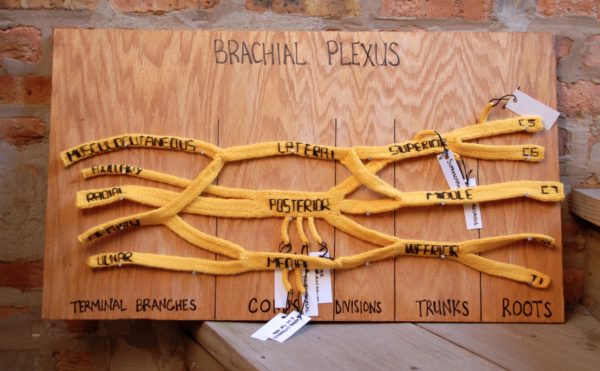

A hand-knit brachial plexus isn't something you see every day, so when I saw one while scrolling about the internet, I had to learn the backstory. (It's pretty incredible.)

The knitted brachial plexus, intestines, eye and other body parts are the creation of Daniel Lam, MD, a pediatrics resident at the University of Colorado who started knitting parts of the human body as a medical student because he found it was the easiest way to unravel, learn and memorize the intricacies of human anatomy.

I corresponded with Lam via email to learn more about the stitched works of art featured on his website, Masculiknity, and what inspired him to pick up a pair of knitting needles in the first place. Here's what he had to say:

When did you first start knitting and why?

To impress a girl in the eighth grade, which I still cringe at when I think back to it.

When did you start knitting human anatomy and what made you think to do it?

I started during my second year of medical school while I was TAing my anatomy course. Having to teach the parts of anatomy that I struggled the most with forced me to think of alternative ways of understanding it. And while most curricula have really good atlases and textbooks and review PowerPoints, I realized that there were very few 3-dimensional, interactive anatomy tools, which is precisely what’s needed when teaching such spatially complex subject matter.

Where do the knitting patterns for each body part come from?

I make them myself. I take bits and pieces of other patterns and simpler knitting techniques to get the (approximate) shapes I want. It’s a lot of trial and error. I have about 10 pancreases of varying sizes and shapes in a drawer somewhere.

What is it about the knitting process (or the finished product) that helps you learn and remember?

Well, for me as the knitter, the planning of the pattern and assembly really cements the ideas in my mind.

And for the learners, I think it’s the interactive component to it, and the fact that they get to put their hands on something and manipulate it in whatever way it takes for the ideas to really click for them and them specifically.

How hard is it to make a knit model that’s accurate enough to use as a study guide?

When I first started, I used to get caught up in trying to make everything anatomically correct. But I quickly learned that that’s impossible. Yarn will never be tissue. I mean, I’m good, but I’m not that good.

So now I pick just one concept — usually the most confusing/arbitrary one — and then I aim all goals at making that one concept more tangible. For example, with my abdominal viscera, my main goal was to clarify the omental spaces and how they connected with respect to the various organs surrounding it, and I just learned to live with the fact that I left out all vasculature and that the kidneys are bigger than the spleen.

What was the most labor-intensive body part you’ve knit?

I remember when I was making the eyeball and setting it up in a shoebox so that each extraocular muscle moved the eye the way it physiologically was supposed to. It was a frustrating and painstaking process, but I’m pretty sure I will never forget it.

Conceptually it’s all physics and the sum of forces, but I went through three shoeboxes with an X-Acto knife until 2 a.m. trying to get it as accurate as possible.

Do you have any advice for people who are just starting knitting?

I strongly encourage it. It’s so good for so many reasons, but mostly because it’s fun and productive and so unlike all the other things out there that we fill our lives with.

What’s next for your knitting — and medical — career?

Currently, I’m a pediatrics resident at the University of Colorado. I am also knitting a layered tunic.

Patterns for some of Daniel's creations are available online.

Photos by Daniel Lam