For a cell, the suffix "-osis" spells trouble.

You may have heard of "apoptosis," a well-known and well-studied form of cell death, but what about necrosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, or NETosis?

While it may sound counterintuitive, a variety of self-destruct buttons can actually be a good thing. Sometimes death is necessary -- as a fetus develops, cell death helps sculpt tissue into its correct form. Sometimes it's protective -- during an infection, cell death might save the healthy cells from disease. But too much or unregulated cell death can quickly become problematic.

After writing a story detailing a type of cell death I hadn't known much about, I started to wonder what other forms of cell death were out there.

I reached out to four Stanford researchers -- Jan Carette, PhD, assistant professor of microbiology and immunology; Denise Monack, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology; James Ferrell, MD, PhD, professor of chemical and systems biology and of biochemistry; and Scott Dixon, PhD, assistant professor of biology -- and asked them to help me break down just how many ways a cell can meet its maker.

Apoptosis -- the classic cell death

If you've heard of any form of cell death, it's likely apoptosis. This was the first form of cell death to really be investigated on a molecular level, the researchers told me. It's involved in normal tissue formation such as when the spaces between your fingers are created in utero or as a defense mechanism in cancers and infections.

Unchecked, however, apoptosis can cause great harm as in some neurodegenerative diseases, like multiple sclerosis. Currently, apoptosis is probably the most well-understood version of cell death, but there's still room to learn more, as Stanford scientists demonstrated with the recent discovery that apoptosis spreads through a single cell a lot like falling dominoes.

Necrosis -- the "other" cell death

For many years, scientists had really only identified apoptosis, leaving everything else as necrosis, which at the time basically amounted to, "We don't have a molecular explanation for this type of cell death." Today, necrosis is still somewhat of an umbrella term for pathways of undefined death, much of which stems from some kind of trauma like frostbite, a burn or a laceration.

NETosis -- the net-throwing cell death

It's no joke, NETosis involves death by little structures that look like nets. Specifically, these "nets" come from a type of immune cell called a neutrophil -- NET stands for neutrophil extracellular trap.

Neutrophils are one of the first immune cells to respond to a microbial invader or infection. Microbial infections can spark NETosis, leading to an unleashing of anti-microbial net trap that target invading microbes such as bacteria, viruses, parasites or fungi.

On the flip side, NETosis can also occur in autoimmune diseases like lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, when the net-like defense structures overstimulate an immune response.

Pyroptosis -- the alarm-sounding cell death

Pyroptosis is also an infection-related form of cell death, but it's "pro-inflammatory" meaning that it comes with something of an alert system that lets neighboring cells know there's infectious trouble on the loose. This form of cell death primarily occurs in immune cells too, and when infected, pyroptosis causes the cells to release their danger signals and then swell and burst.

Ferroptosis -- the newest cell death

Ferroptosis is the most recently named version of cell death, and also the most obscure. From what researchers understand, ferroptosis occurs when a cell is low on a particular protein building block called cysteine. In the cell, cysteine helps to produce a type of antioxidant, which protects against damage-inflicting molecules called reactive oxygen species.

Ferroptosis can occur when a cell is cut off from blood -- its cysteine stores shrink, reactive oxygen species pile up, and the cell dies. Only identified in 2012, scientists are still figuring out its role.

For now at least, those are most of the major types of cell death. By learning more about them, researchers hope to develop new therapies to thwart disease, extending and improving life.

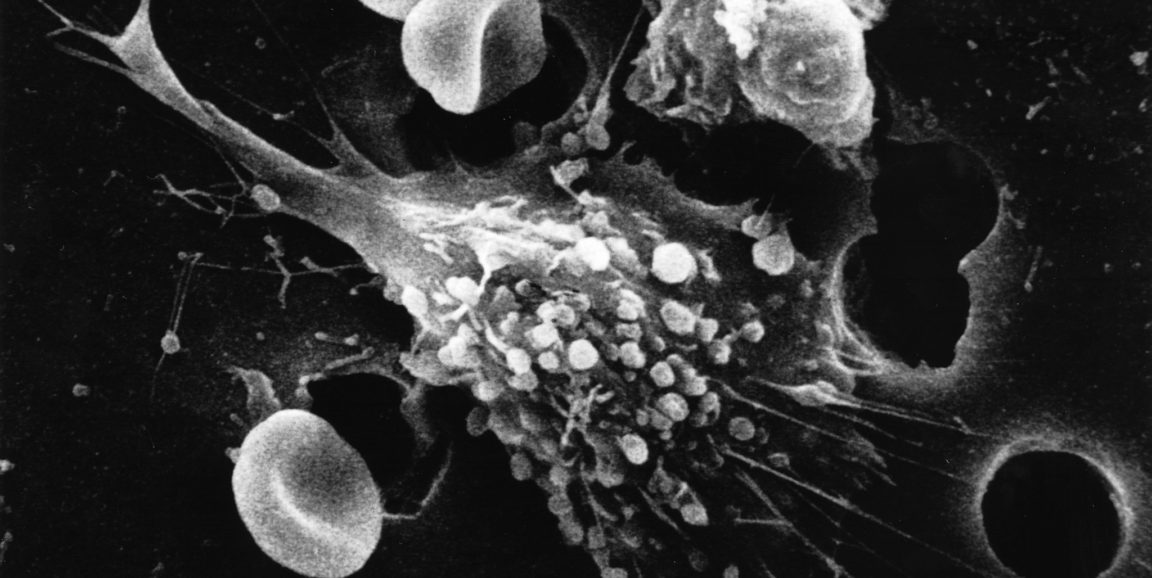

Photo by Susan Arnold