Dark and unnamed drifters of the universe have begun to threaten the stability of our world. Your assignment, should you choose to accept it, is to analyze the DNA data collected on these foreign adversaries so that we may unlock the secrets of their biology.

This was the mission for hundreds of thousands of online gamers immersed in the massive multi-player computer game EVE online. It's a globally popular, space-based role-playing game where gamers can embark on their own sci-fi adventure, and for one year, it served as a platform for an enormous citizen science effort called Project Discovery.

A paper describing the work was published in Nature Biotechnology.

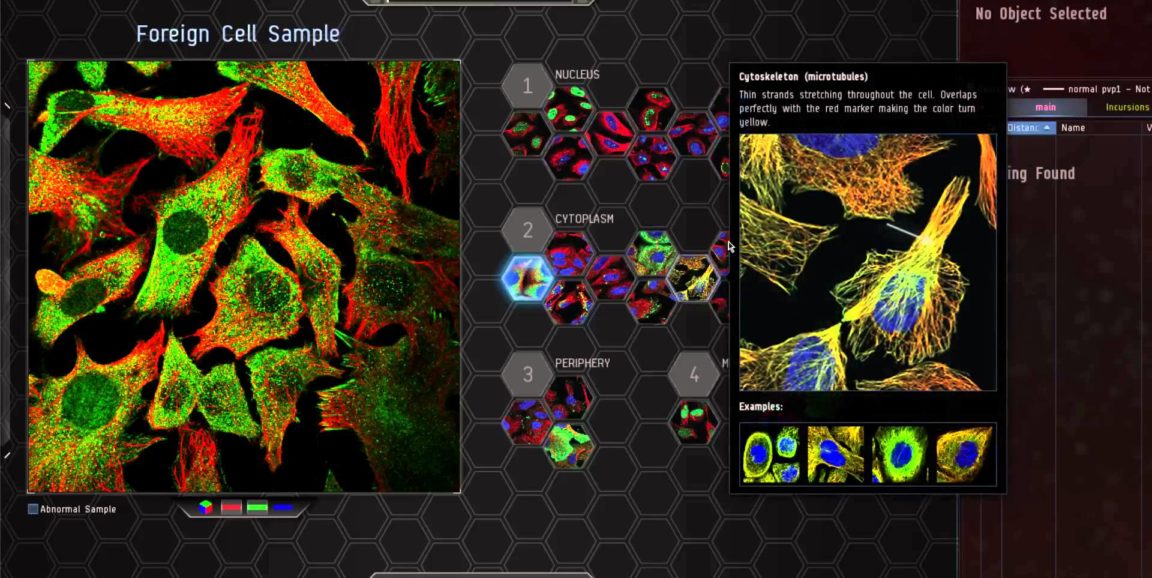

Led by Emma Lundberg, PhD, associate professor at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology and visiting associate professor of genetics at Stanford, Project Discovery aimed to improve the understanding of proteins' locations in cells by enlisting the help of EVE computer gamers. (Although in the game, these images of the proteins are billed as pieces of Drifter DNA).

EVE is highly involved, and sometimes players have to wait around for plot lines to unfurl. So in their down time, gamers could access Project Discovery, a "mini game" where they are trained to recognize images from the Human Protein Atlas of different proteins and the regions of a cell where those proteins are generally found. Over the course of one year, about 300,000 users spent a combined total of 70 working years (a full-time employee works about 2,087 hours in one year) playing Project Discovery.

Some learned the science, some didn't -- it was really just a matching game. Different shapes, structures and colors pair with particular cellular niches, and gamers matched the corresponding pairs. To incentivize gamers, those who engaged with Project Discovery were rewarded with tokens that they could use in the EVE universe.

From the effort, Lundberg has earned a small claim to fame: She has an avatar that describes Project Discovery to all who want to "decode Drifter DNA" in the game. "I'm probably one of the few living scientists that's in a computer game," she told me with a laugh.

The Project Discovery team collected matching data for one year, after which they analyzed the gamers' accuracy. It turned out that the gamers performed just as well as AI image classification models. "It felt good to know that our crowdsourcing yielded quality data regardless of the user's motivations," Lundberg said.

The gamers' data even helped refine some already-known locations of proteins, clarifying where the proteins were in the cell.

"We also were able to highlight a structure that's found in the cell called 'rods and rings,'" Lundberg said. "The function of rods and rings is not really understood, but the gamers found another 10 types of proteins that exist in these structures, and we hope discoveries like this can help scientists understand what its role is in the cell."

The nice thing about Project Discovery, Lundberg says, is that it can live on through other scientists who can reuse the framework -- with their own images -- for their own purposes. "Now, a research group in Switzerland is using it to get help in discovering exoplanets," she said. "So we hope that Project Discovery can help other scientists do their work cheaper, faster and more effectively."

Next up, Lundberg is issuing a new challenge to the public. Run by a tech start-up and launching in September, the challenge asks the public to devise an algorithm that can match proteins and their in-cell niches better than professionally-trained biologists.

While that challenge is not a game, Lundberg said she hopes to continue to harness gamification as a way to engage hundreds of thousands of citizen scientists in the future.

Screenshot of Project Discovery courtesy of Emma Lundberg