As our parents age, we worry about them falling. Falls in older adults can lead to emergency department visits, hospital admissions and even death. At best, falls cause anxiety for patients and their loved ones.

Studies show that regular exercise can reduce the risk of falling, but it is unclear which kind of exercise is most effective for older adults. Now, a new multi-institutional clinical trial has assessed the effectiveness of two proven exercise interventions -- tai chi and a multimodal exercise program -- which were compared to a control intervention of stretching.

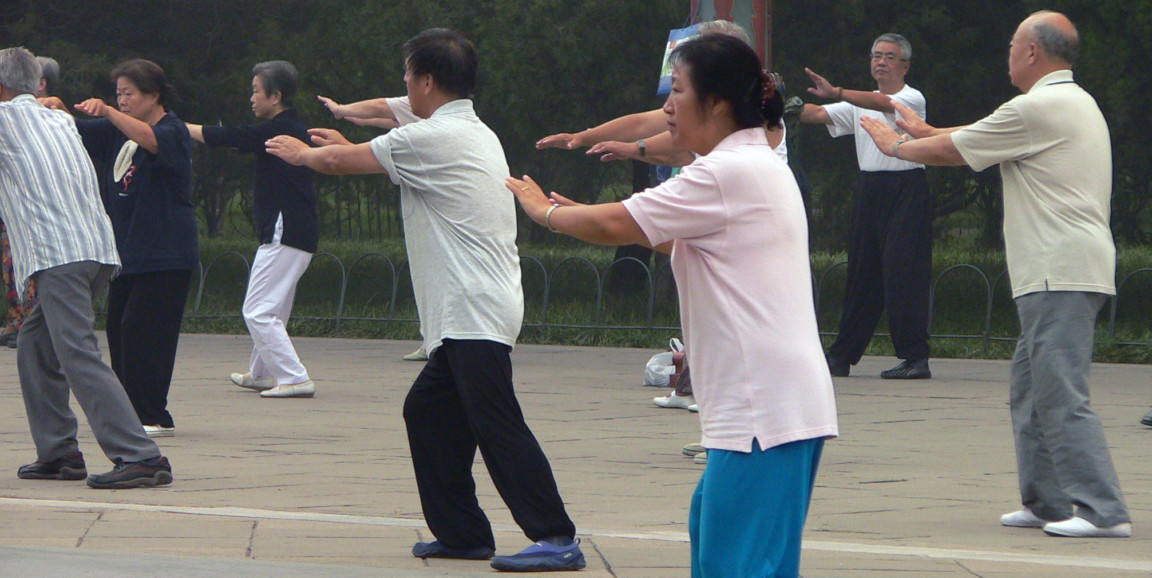

Tai chi is an ancient Chinese practice involving a series of movements performed in a slow, focused manner. Traditionally, people practicing tai chi flow between as many as 100 different postures. However, the study investigated a simplified form focused on eight core movements that were selected to improve balance for older adults.

The researchers also evaluated a more conventional, multimodal exercise program that incorporated aerobic, strength, balance and flexibility exercises.

The 670 participants were 70 years and older with a high risk of falling, based on impaired mobility or a history of falling in the previous year. They performed a 60-minute exercise session twice weekly for 24 weeks, which was randomly assigned as either tai chi balance training, multimodal exercise or stretching.

These interventions were primarily evaluated by the incidence of falls, which were self-reported monthly and then confirmed using follow-up appointments and medical records.

The study found tai chi balance training to be more effective than conventional exercise approaches for reducing falls, as recently reported in JAMA Internal Medicine. During the six months, 152 falls occurred among 85 participants in the tai chi group, 218 falls among 112 participants in the multimodal exercise group and 363 falls among 127 participants in the stretching group.

TC Cowles, a nurse and program manager at Stanford Health Care's Supportive Care Program, said he wasn't surprised that tai chi reduced falls. These new findings agree with previous smaller studies, including a meta-analysis study. However, he said he was very excited to have it confirmed with so many participants.

"This is the largest study I've seen focused on tai chi as a fall prevention. It's encouraging to see that it reduces falls by 58 percent compared to the stretching exercises and 31 percent compared to a multimodal exercise intervention," Cowles said.

Cowles manages similar tai chi classes on Tuesdays through the Neuroscience Supportive Care Program and on Thursdays through the Cancer Supportive Care Program. These classes are very popular -- almost 900 people have attended the tai chi classes in the last year, he said. Many of the participants are in their mid-60s or 70s.

"I like the practice because it is modifiable. You can start in a chair with arms to decrease the risk of falling during some of the movements. And if you strengthen, you can advance to a standing position," said Cowles.

According to Cowles, however, attending consistently is key. "Patients that come regularly report that they feel less wobbly and can walk better on their own," he said. "They also build core strength, so they can hold themselves upright for longer periods of time. And they build confidence, so they're more apt to participate in other programs and activities."

Stanford Supportive Care Programs also offer weekly classes on qigong, meditation and yoga, which can increase stability too. And all the classes are free and open to the community.

Photo by Craig Nagy