When Alex Sable-Smith’s phone jarred him from a deep sleep at 3 a.m. Wednesday and he saw that it was his mother calling, his first groggy reaction — as would be anyone’s — was to feel concerned.

She was back in Columbia, Missouri, where he’d grown up. He was in Palo Alto, not yet completely settled into a faculty position after completing a fellowship in hospice and palliative care at Stanford.

“Did you see my text?” she asked.

He hadn’t.

It said: Dad won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, she told him.

Seriously? Sable-Smith laughed. He felt a storm of emotion: excitement, happiness, pride.

“I was surprised,” he said, “but not surprised.”

A faculty member at the University of Missouri for more than four decades, his father, George Smith, PhD, was best known in scientific circles for a discovery he made in 1985, the year his first son was born. He laid the groundwork for a method called phage display in which a bacteriophage — a virus that infects bacteria — is used to identify unknown genes encoding a known protein of interest.

Other scientists, including Gregory Winter, PhD, with whom he shares the Nobel, used the phage display method to develop pharmaceuticals based on human antibodies, including Humira, which is used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, Crohn’s disease and other ailments. Frances Arnold, PhD, a professor at the California Institute of Technology, also was named a laureate in chemistry on Wednesday.

There had been talk over the years about a Nobel Prize, mostly by Smith’s colleagues, but Smith shrugged it off — even when the questions came from his young sons.

“Science was just woven into the fabric of life, growing up with him,” Sable-Smith said. “He would ride his bike into the lab when we were young, towing me or my brother on the bike carrier with him. We would sit in his office and play with test tubes and pipettes.”

In one oft-told family anecdote, Sable-Smith held up a square sponge in the bathtub and told his father it was a sequencing gel, an old method for decoding DNA. “That didn’t seem extraordinary at the time for me,” he said.

Sable-Smith didn’t fully understand his father’s discovery until college, and he didn’t realize the broad impact until medical school, when he was learning about the drug Humira and thinking about antibodies.

On Wednesday, Sable-Smith showed off his pride in his father’s award with an early-morning tweet that also paid tribute to their shared “goofy” sense of humor.

Retweeting the Nobel Prize account’s technical description of the science and the phage display infographic, he wrote a literal description of the illustration: “My dad just won the #Nobel prize for putting the red thingy into the blue thingy so it hooks on to the yellow thingy! #NobelPrize #phagedisplay #chemistry”

(“My dad too!” replied his brother in a tweet.)

More than 11,000 people hit “like”.

But in all seriousness, as Sable-Smith contemplates finding a tuxedo with white tie and tails and a ticket to the Stockholm ceremony, he’s also reflecting on how his father influenced his aspirations and outlook.

For one thing, Sable-Smith says he decided to be a physician-educator because of Smith’s emphasis on education. For another, he says his father engendered an appreciation of “the spirit of science,” embodied as curiosity, exploration and creativity. He told me:

My dad sees science and discovery as a public good — science is done to better understand the world. And I think he really, firmly believes that the outcome of scientific advancements should be accessible to everyone.

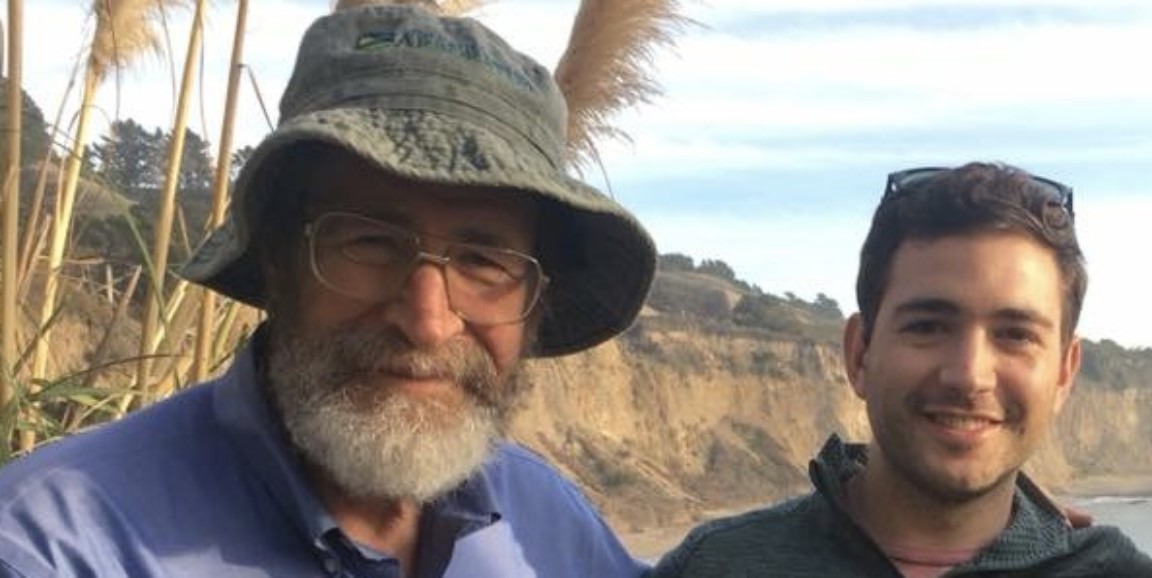

Photo courtesy of Alex Sable-Smith