I intended to write one news article about FAST, the science exploration program created by a team of Stanford science graduate students that has touched the lives of scores of East San Jose youth. Simple, short and straightforward. But as I started talking and exchanging emails with the program's founders, its current leaders and with the students themselves, I realized I just couldn't do it, there was too much to say.

As founder Cooper Galvin, a Stanford graduate student in biophysics, explained: "we stumbled onto something." That something was a belief that anyone, everyone, has the potential to contribute to science and that when an individual is empowered to follow his or her curiosity, great things can happen. The FAST leaders also had the determination to bring their beliefs to life.

Again and again, I heard about the transformational power of the program.

"The biggest change we've seen in the kids that take part in FAST is they begin to trust the learning process itself," Andrew P. Hill High School science teacher Patrick Allamandola told me. "In science, it's not so much interesting when you get the right answer. It's when you hit a roadblock and need to figure out the cause and figure out the solution."

When FAST alum Yen Ta enrolled in FAST, she didn't want to bother her hard-working single mom by telling her about it. "I want to succeed so that in the future I can take care of her," Ta said.

Ta was thinking she wanted to go into the medical field but wasn't quite sure how to get there. "FAST definitely gave me a push," she said. "I think it's had a huge effect on my community."

Now, she's in community college working to be an anesthesiologist.

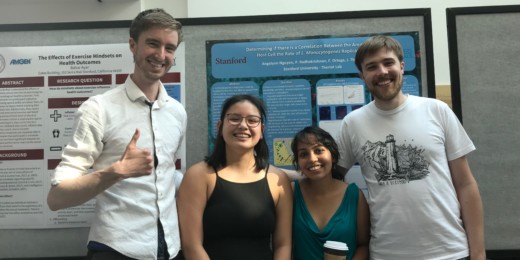

FAST also introduced Brianna Rivera, an alum now at San Jose State University, to bioengineering. "I had no idea that bioengineering existed," Rivera told me. Her parents, from Mexico, did not graduate from high school.

"The mentors are amazing," Rivera said. "They are not just there to help you with your experiments. They really are life mentors."

The experience is also beneficial for the mentors, Stanford students told me.

"I think at first the commitment was really scary to me and scary for every mentor who signs up," Galvin told me. "Then it clicks that FAST is not something off [the career] pathway, it is something that makes us better people."

The Stanford mentors and leaders have formed a close-knit community, FAST development officer Erin McCaffrey, a graduate student in immunology, told me. "It sounds really intimidating having to spend 13 or 14 Saturdays of your year at the high school. During the week you're stressed and there's no time, but then you go there and you work with the students and it's just an incredibly fun and rewarding time," she explained.

The mentors meet up for dinner after each session, gather together for an annual barbecue, and pitch in when someone else is struggling with qualifying exams or other obligations, she said. "The most meaningful thing I did in my first year of graduate school was participate in FAST," McCaffrey said.

Katie Liu, a graduate student in chemistry and chief operations officer of FAST, learned about FAST while she was deciding where to attend graduate school. The opportunity to take part sealed her decision to attend Stanford. "Community engagement has always been very important in my life."

But even for Liu, the commitment seemed overwhelming at first. "I didn't know there was that time in the schedule," Liu said. "But I saw how awesome the community was and how awesome the students were and I just kept coming back."

I heard from both FAST students and mentors that the relationship they form often extends beyond the science project. Such was the case with Angelynn Nguyen, a senior at Andrew Hill High School, and her mentor of two years, Prathima Radhakrishnan, a Stanford biophysics graduate student who moved with the lab of Julie Theriot, PhD, to the University of Washington this fall.

"We were kind of like pen pals," Nguyen told me. "She's a really cool mentor and we can talk about a lot of things together."

"We very much bonded," Radhakrishnan reflected. "I let her know she was really special and could do anything she wants to do. I'm glad she has gotten so much out of the program."

In her second year, Nguyen found herself intrigued by biofilms, the substance such as dental plaque that protects bacteria and fungi. Nguyen found that by mixing two antifungals, she could weaken the biofilm and more effectively eliminate the fungal cells. "It was a really exciting result for me," Nguyen said. She took the project all the way to the state science fair.

With Radhakrishnan's help, Nguyen joined Stanford's RISE Summer Internship Program this summer. The seven-week program gives high school students the opportunity to assist with research in a Stanford lab. FAST has proven to be a bridge to RISE -- Ponce also conducted research at Stanford this summer. Both were also chosen to give the closing ceremony speech for the RISE program, Galvin said.

This connection, to larger places and more expansive ideas, is the true benefit FAST to provides to the high schoolers, Allamandola said:

It's a change in perception about themselves and about how they can interact with the world around them... Through their mentors, they've been exposed to something bigger. It's more of an attitude to be curious... and the belief that you can go out and do cool and interesting things. You have someone to show you the way.

After hearing all of these inspirational stories, I found myself wondering: What will FAST look like in the future?

This is the third installment of a four-part series on FAST.

Photo of Brianna Rivera and Vivek Gupta, a Stanford graduate student in mechanical engineering and the chief financial officer of FAST, courtesy of FAST