Depression is a disease that affects people from all backgrounds, at all stages of life. For Rebecca C., a 55-year-old, former salon owner and single mother, her most recent experience with depression was triggered by an ineffective operation that left her in so much abdominal and pelvic pain that she was unable to work.

This resulted in a difficult financial situation that almost caused her to lose her home. During this time, some mornings she could not bring herself to get out of bed. She lost interest in things that used to bring her joy, like cooking, baking and shopping. She had trouble sleeping and even experienced suicidal thoughts.

Her physician prescribed antidepressants, but she did not always take them regularly due to side effects that included weight gain and itchiness. After several months, Ms. C started to feel better, but some mild symptoms persisted. While her experiences are unique, Ms. C's primary symptoms and the trajectory of her depression are somewhat typical.

Worldwide, depression affects more than 300 million people, yet fewer than half receive adequate treatment. Barriers to effective care include lack of resources, social stigma, and societal and clinical inattention to mental health issues, including missed diagnosis. Through this blog series, I, along with Stanford professor and primary care physician Randall Stafford, MD, PhD, hope to provide greater insight into this often-misunderstood disease, starting with an overview of the disease itself.

Symptoms of depression are most concerning if they appear consistently for at least two weeks (multiple symptoms are common). They include:

- Depressed mood

- Marked loss of interest in daily activities

- Significant weight loss or weight gain

- Thinking and/or moving noticeably slower

- Loss of energy

- Persistent or excessive feelings of worthlessness or guilt

- Diminished ability to think or concentrate

- Suicidal thoughts

Like all other chronic diseases, including diabetes, cancer, and heart disease, depression is extremely complex and variable. Not only does it come in different forms, it presents in varying degrees of intensity and can overlap with other conditions.

Some people experience a reactive depression, generally in response to a personal loss or tragedy, like death of a loved one, losing a job, or in Ms. C.'s case, a difficult recovery from surgery. Others experience depression even when everything around them is going well.

Depression can be mild, but it can also leave an individual incapable of functioning and lead them to have suicidal thoughts or behaviors. Generally, depression is treated with a combination of medication and talk therapy. Depressive symptoms can also overlap with other conditions, including anxiety, bipolar disorder, addiction, personality disorder, and even dementia.

Like other chronic diseases, depression has a complex set of causes, which are not completely understood. Currently, there are two complementary models of how depression works.

The cognitive theory of depression suggests that depression results from negative thoughts generated by dysfunctional beliefs. The more negative thoughts an individual experiences, the more depressed that person becomes. These beliefs can shape and even distort how someone experiences the world. Individuals with depression tend to magnify the meaning of negative events and minimize positive events. These unconscious tendencies cause depression to begin and persist, but they can often be confronted and corrected using talk therapy.

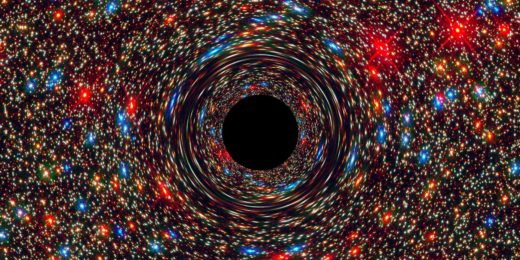

A molecular model of depression suggests that depression's underlying cause is an imbalance of chemical neurotransmitters in the brain, including serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine. This imbalance may result, in part, from social or psychological cues. This model of depression has informed the development of our most effective antidepressant medications to date, however they are not universally effective.

There is a clear difference between a healthy brain and the brain of someone with depression, as the brain scans below illustrate.

Depression has no cure, but it is treatable through a combination of approaches, especially when it is recognized and properly diagnosed. Unfortunately, despite its immense impact on individuals and families, depression is often not taken seriously enough.

This is first in a series of blog posts, Taking Depression Seriously, that aims to help patients and family members better understand depression as a chronic disease and more successfully navigate the health care system. The next blog will focus on barriers to mental health care and how to overcome them. The patient's name has been changed to maintain privacy.

Sophia Xiao is a master's degree student in Community Health and Prevention Research (CHPR) at Stanford who studies barriers to health care and the role of public health education in improving access to care. Stanford professor and primary care physician Randall Stafford, MD, PhD, studies strategies to improve chronic disease treatment, including increasing the role of patients in their health care.

Photo by tadamichi