They made a mistake. I don't deserve this. I don't belong.

Unqualified.

Fraud.

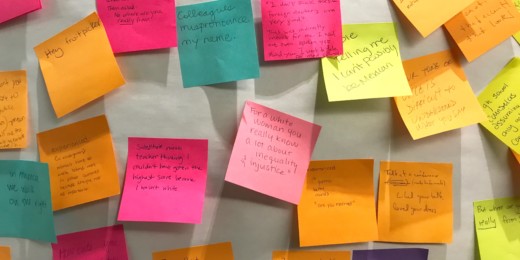

The dark language of self-doubt filled a big screen at the front of the room as medical students, trainees and others seated at round tables typed in their personal definitions of impostor syndrome.

This session, on impostor syndrome, was part of the second annual Diversity & Inclusion Forum, a morning of workshops addressing the barriers that keep underrepresented groups from feeling welcome and included in the medical profession.

"We know that diversity in the medical workforce still has a long way to go. The focus has really been on recruitment, but not as much looking at inclusion, retention and equity," said Lahia Yemane, MD, a pediatrician who co-directs the Leadership Education in Advancing Diversity (LEAD) Program, which organized the forum. "Our ultimate goal is to strengthen the pipeline in academic medicine and ensure our core values of diversity, equity and inclusion are reflected in our medical programs, leadership and culture."

LEAD is a 10-month program -- open to residents and fellows from seven departments -- that provides leadership training and mentoring to advance the study of diversity and inclusion. LEAD participants developed the workshops delivered at the event, which included topics such as "stereotype threat" in medical trainees (the fear of doing something that would confirm negative perceptions about your minority), the use of stigmatizing language in patient settings and other issues related to diversity.

One persistent challenge for women and minorities is impostor syndrome, a term coined in 1978 that is used to describe the feeling of being intellectually unworthy, or the perception that success is due to luck or hard work, and not ability.

"I'm just realizing I have this," one participant volunteered. She shared her experience of getting hired as a manager right out of college, and later finding the resumes of the other candidates. "I thought, 'These people have made a mistake. All the other candidates were way more qualified than me.' I spent the whole time on that job ... trying to figure out why they hired me."

The research is limited on impostor syndrome in the medical workforce, the presenters said, but a study of impostor syndrome and burnout among medical students found twice as many women experienced feelings of self-doubt compared to men. In another study, family medicine residents with impostor syndrome were more likely to also suffer from depression, anxiety and the fear that they wouldn't be ready to practice medicine after residency, despite their training.

After discussing several scenarios, attendees brainstormed solutions that could help younger faculty and members of underrepresented minorities feel that they belong.

- Sponsor junior colleagues

Lisa Chamberlain, MD, an associate professor of pediatrics, reflected on an experience running a faculty search committee where all the other committee members were significantly more senior. Looking back, she realized it was a missed opportunity to make junior colleagues feel valued.

"We could have done a better job in involving junior faculty in our search committee," she said. Inviting them to be involved in an important hiring decision would have sent the message that "'We trust your voice. You belong there,'" she added.

Lahia Yemane, MD, right, with Carmin Powell, MD

Kamaal Jones, MD, right, and Hannah Keppler, MD

From left: Caroline Okorie, MD, Mehreen Iqbal, MD, and Heidi Feldman, MD

- Show your vulnerability

Nina Horowitz, a graduate student in bioengineering, said it would help if people shared their feelings with each other instead of suffering alone thinking that everyone else is smarter than them.

"If you say ... you are experiencing something like this, other people will say the same thing," Horowitz said. "It takes a lot of courage to be the first one."

Similarly, Chamberlain said sharing stories of personal rejection could be reassuring for junior colleagues struggling with feelings of inadequacy.

"I submit grants and I get rejected all the time," she said. "I have met with success, but it's only because I get up to bat so often."

- Remember your accomplishments

Keep thank-you notes from patients or a list of accomplishments where you can refer in times of self-doubt, said presenter Elana Feldman, MD, a second-year pediatric resident.

And a personal mantra can help too, said Tamara Dunn, MD, clinical assistant professor of hematology.

"Set an alarm and say 'I love you, I respect you, I admire you, I got this,'" Dunn said. "Just tell yourself that over and over again, because kindness and compassion can go a long way."

Photos by Kevin Meynell: Dimitri Augustin, MD, Nancy Rivera, MD, and Elana Feldman, MD, presenting on impostor syndrome