Death is a part of life. We know every person will eventually die, yet when the time comes, our conversations about death are among the toughest we'll ever have.

Talking about death is difficult for many reasons. From a doctor's perspective, having a patient who cannot be healed may feel like failure. For patients, stopping treatment or forgoing a therapy or surgery may seem like quitting.

Every person discusses death their own way, and even close family members may differ in the way they approach conversations about the end of life and death, depending on their personal experiences, religious and cultural beliefs and their environment.

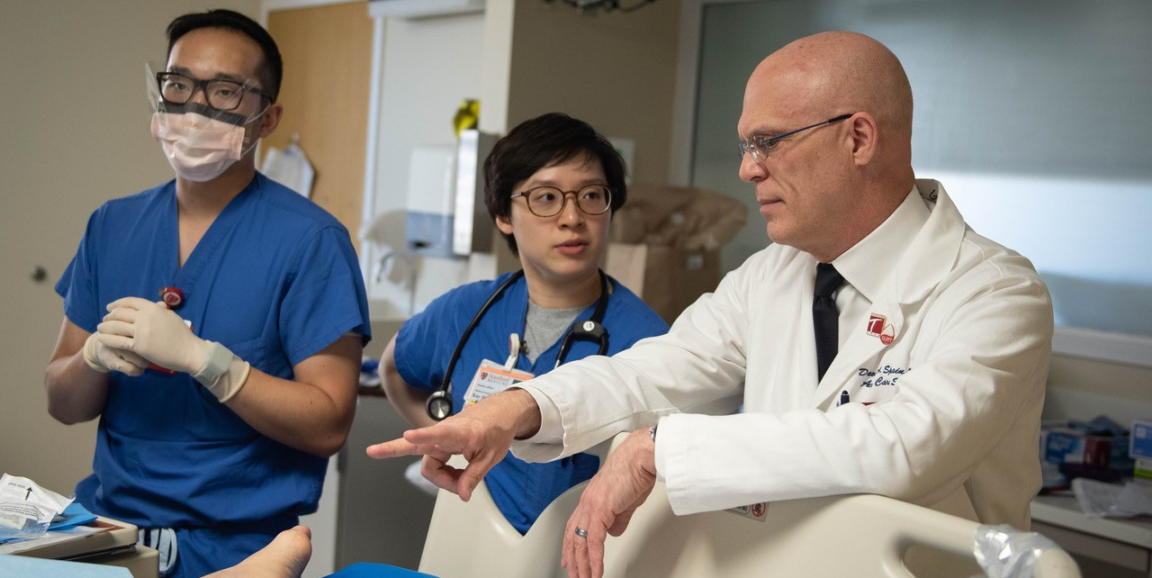

As Stanford's chief of acute care surgery, David Spain, MD, has an uncommon perspective on life and death.

His office lies at the end of a complex set of halls and corridors in Stanford Hospital. After several wrong turns along my way to meet with him, I found myself in front of a gurney flanked by two people who pushed it and its cargo -- a human body shrouded in black -- into the elevator yawning open nearby.

I pressed my back into the brick wall, slid down a fraction of an inch and exhaled a puff of air. I planned to discuss death in 25 minutes. Death was early and I wasn't ready. As I waited outside Spain's office, that thought had a field day in my head, uncorking bottled memories of people and pets I've loved and lost.

My ghosts and uneasiness evaporated once I met Spain. He radiates calm, a skill he must have perfected over years of caring for people who were in car crashes, shootings, stabbings, or had unforeseen health emergencies.

"How do doctors deal with the topic of patient death?" I asked abruptly. Spain's "ready for anything" demeanor prompted me to start with a tough question -- something I rarely do.

Handling death is hard under any circumstances, Spain explained, but there's a particular set of challenges surrounding the unexpected loss of life.

"Think of how hard it is to deal with the death of somebody who had been ill for a while and you've had time to prepare," Spain said. "We have cases where people woke up on a random Thursday morning and thought their lives were normal. Then their loved one got hit by a truck and they're gone. And we have to go out and tell them that. Completely out of the blue." Spain paused for a few seconds. "Yeah, there's no formal training on how you do that."

Some medical schools and training programs are starting to develop curriculum around having difficult conversations with patients and their families, but not many, said Spain, who is the David L. Gregg professor in general surgery.

Spain learned to discuss death and deliver bad news on the job, he told me. Today, many medical students and doctors learn the same way -- by observing as other doctors have these conversations.

Spain explained that the recent growth of palliative care as a specialty has helped him, and doctors like him, frame discussions in situations where there's time to talk to patients, or their families, about their choices. "Some of their principles and techniques are really helpful," he said.

"It's important to say the actual words," Spain said. "You can't use euphemisms. You have to say, 'They are dead.' You can't say, 'They have passed. They're gone.' You actually have to say the words. But how you do it, and how you phrase it? ... There's almost no science, data or literature behind that to guide you."

Death typically occurs one of three ways, Spain said: Completely out of the blue; after a sudden trauma or illness that gives the doctor a little time to prepare the patient and family; or a more progressive path towards death after an illness spanning months to years that gives the patient and family time to prepare. Knowing how to discuss death in each scenario is poorly understood and needs to be studied more, Spain told me. This information could help people have more helpful and meaningful conversations about the end of life and death.

"Years ago," Spain said, "a priest mentioned how rare it is for most people in our culture to be there the instant somebody dies. ... I remember sitting in church doing the math in my head thinking, 'How many times has that happened to me? How many times have I physically been present the moment somebody died?' This was 20 years ago and the number was several hundred then."

The sum of these experiences has changed the way he approaches life, Spain said.

"I don't argue with my wife," he said. "I cannot tell you the number of times I've seen someone who gets up, goes to work, gets in an accident on the way and dies. ... I just don't argue with my wife."

This is first in a series of Discussing Death blog posts designed to help people have more helpful and meaningful conversations about end of life care and death. The next blog will feature insight from Stanford Medicine palliative care expert Stephanie Harman, MD.

Photo by Rachel Baker of Jason Teng, MD, from left, medical student Kay Hung and David Spain, MD.