In the first part of the story of his accident and recovery, Anthony Macchio-Young receives emergency surgery to fix bleeding in his brain from a bike accident and spends nearly three weeks in Stanford Hospital's intensive care unit.

At Kentfield Hospital, a long-term acute care facility in northern California, where Anthony Macchio-Young spent two months, his steps toward independence were small, but significant. He had been given a tracheostomy, an opening in his throat to help him breathe, so he couldn't talk. But he painstakingly spelled out sentences, letter by letter, on a dry-erase alphabet board.

After weeks of practice, he managed to stand, supported by horizontal parallel bars, for 23 minutes. And he practiced putting pegs in a board with his right hand -- at that point, he still couldn't move his left.

He also suffered from occasional brain storms, a symptom of traumatic brain injury recovery when the sympathetic nervous system goes into overdrive, creating a stress response. His heart raced, his breathing became rapid, his body temperature rose. During one of these episodes, his mother, Kim Young, spent hours massaging his limbs, hoping to make him more comfortable.

Back home in South Carolina, his friends and family organized a fundraiser at a restaurant that Macchio-Young helped open five years earlier. They auctioned off various donations, including restaurant meals and hotel stays. It netted them $15,000, which the family spent flying him to Atlanta with a nurse.

There, on April 21, 11 weeks after his injury, he checked into Shepherd Center, which specializes in rehabilitation of spinal cord and brain injuries. He was still an inpatient, but he was much closer to his parents in South Carolina and other family members and friends.

At the hospital, Macchio-Young steadily racked up a number of milestones since his accident. His said his first word, "hi," soon after arriving and having his tracheostomy removed. He stood on his own. He walked with a walker. He gradually gained use of his left hand.

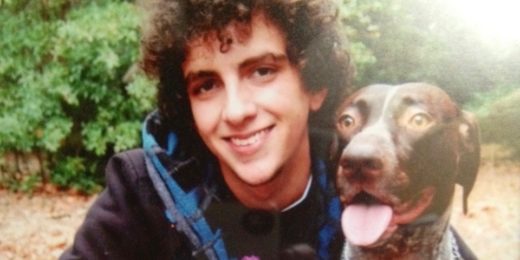

His mother stayed nearby, as she had since she flew out to San Francisco, and his father was able to visit frequently, once bringing their German short-haired pointer, Madison. Macchio-Young told his dad, "I just want to be able to talk well enough so Madison can understand me." He succeeded: Now, Madison obeys when he tells her "sit," "no beg," and "bed."

He also underwent more surgeries, on his hand and foot, to release tendons that had tightened after months of lying in bed. In the meantime, a family friend remodeled his parents' house to accommodate a wheelchair for only the cost of materials.

On Sept. 7, 2013, seven months after his injury, he left Shepherd Center for his parents' house, continued physical therapy as an outpatient and took over writing a blog his father started two days after his accident. In 2016, he began working occasionally as a freelance graphic designer.

Today, Macchio-Young lives in the home where he grew up with Madison; Trinity, another dog he adopted; and a friend of his since the fourth grade. His parents moved into a house in the same neighborhood. He continues his design work and receives occupational therapy twice a month. He has a learner's permit so he can relearn how to drive after his injury, and hopes to drive on his own soon.

The lingering effect of his injury is mostly muscle weakness, including speech dysarthria, which can make him difficult to understand, especially for someone not used to speaking with him. He walks with a cane, using his wheelchair only first thing in the morning, not his best time. He suffered no cognitive damage or problems with sensation.

Odette Harris, MD, the professor of neurosurgery at Stanford Hospital who stopped the bleeding in his brain, said that Macchio-Young's recovery from a severe traumatic brain injury is not typical: Most people who suffer such an injury, if they survive, end up in a vegetative state or severely disabled, she said. "What he had going for him was his age and a lot of family support," Harris said.

Macchio-Young is an upbeat and outgoing guy; he's held onto childhood friends who have helped him through recovery, and he's made friends during rehabilitation and at support groups. These friendships have been critical to his accomplishments, he said. Having an accident like his "shows you who your friends are," he added, noting that some people disappeared from his life afterward. "It also shows you the world is full of kind people."

He's thankful, now, for a number of seemingly random events: that the neighbor who found him had experience recognizing seizures; that he lost his keys so he didn't go inside his apartment; that the ambulance took him to Stanford; and that he chose a career he could pursue after his accident.

He has spoken to middle school kids about the importance of wearing a helmet and to physical therapy students about his recovery. He's also taken part in research about brain injury and hopes to do more.

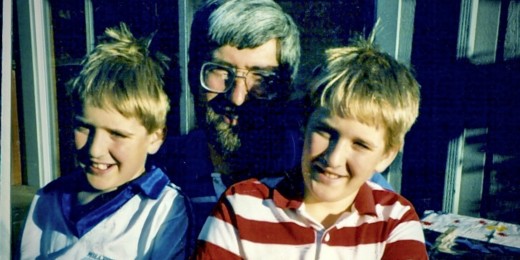

A few years ago, he had to ask his dad, Bill Macchio, to tie his necktie before he attended a family member's wedding. "Not to get too emo on you all," he wrote in his recovery blog, "but I can only hope to tie myself my own tie on my own wedding day one day."

Photos courtesy of Anthony Macchio-Young