In 2013, a few days after Anthony Macchio-Young arrived in the Bay Area with plans to find a job in graphic design, he decided to take his bicycle to San Francisco and pedal to a party.

Hours later, surgeons at Stanford Hospital were opening his skull in a desperate attempt to save his life.

Since that fateful night, Feb. 1, Macchio-Young has had to relearn how to walk and speak, dress and feed himself. His story -- how he progressed from showing no neurological function in the emergency department to working and living independently -- illustrates how devastating a traumatic brain injury is, but also what hope, patience and perseverance can accomplish.

Macchio-Young, now 29, is eager to share it: "I like to think my story inspires other people with a traumatic brain injury to keep trying," he said. "It's hard work, but with hard work and a good attitude, TBI survivors can get better."

Macchio-Young was wearing a helmet when his bike tire caught in a trolley track in San Francisco and he flew off, landing on his head. Initially, he felt well enough to make his way back to San Mateo, where he lived -- he even took a selfie of his bloodied cheek while riding the train home. Then, he took a turn for the worse: Unable to find his keys, he passed out on the doorstep of his apartment building.

A neighbor, seeing him and smelling alcohol from a beer bottle (Port Brewing's Wipeout IPA, to be precise) that had broken in his bag, called the cops, thinking he was drunk. But when she saw a seizure grip his body, she realized he needed medical help. An ambulance arrived to speed the unconscious Macchio-Young to Stanford Hospital.

Odette Harris, MD, a professor of neurosurgery, was on call that night. She said that Macchio-Young's score on the Glasgow Coma Scale -- which measures neurological function -- was 3 out of 15 -- the lowest score possible.

"He came in not well at all," said Harris, who categorized his traumatic brain injury as severe. "He was not waking up, not doing anything... There's a very high mortality rate with that score."

Macchio-Young had a subdural hematoma, a pool of blood outside the brain. Harris performed a left craniotomy: She removed part of his skull so she could drain the blood and repair the artery that was bleeding, then replaced the bone.

Back in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, Macchio-Young's parents, Bill Macchio and Kim Young, woke at 3 a.m. to a phone call from one of the police officers in San Mateo. They caught a flight to San Francisco that day; at Stanford Hospital they found him unconscious, his head wrapped in bandages, his body crossed with tubes and wires.

For two weeks, Macchio-Young's parents barely left his bedside in the intensive care unit. They rode the roller coaster of brain injury recovery: He woke from his coma and raised his fingers when asked, but he also suffered fevers and heart palpitations. On Feb. 21, Harris deemed him stable enough to ride in an ambulance to Kentfield Hospital, a long-term acute care facility north of San Francisco.

There, he began the long journey toward independence, learning to walk, write, speak, eat.

The conclusion of Macchio-Young's story is available here.

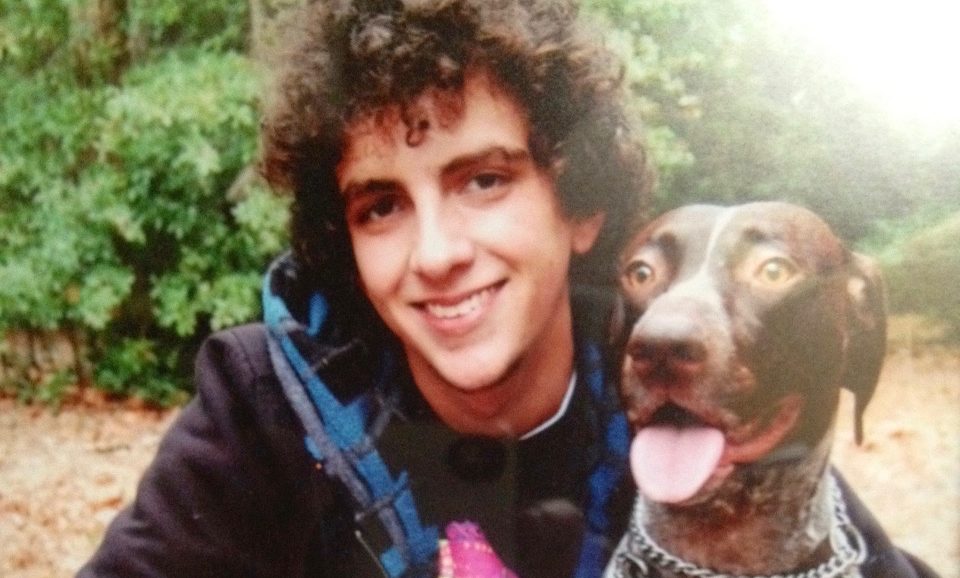

Photos courtesy of Anthony Macchio-Young