Early Monday morning, the 2019 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to three scientists who discovered how cells detect and respond to changes in oxygen levels.

There's a nice Stanford link to this prize: New Nobel laureate Gregg Semenza, MD, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, is collaborating with Stanford's Mark Nicolls, MD, on a way to use Semenza's prizewinning discovery to help lung transplant recipients.

"I was up at 5:30 a.m. emailing and congratulating Gregg," said Nicolls, describing his reaction to the Nobel Prize announcement. "I was absolutely thrilled. It was well deserved."

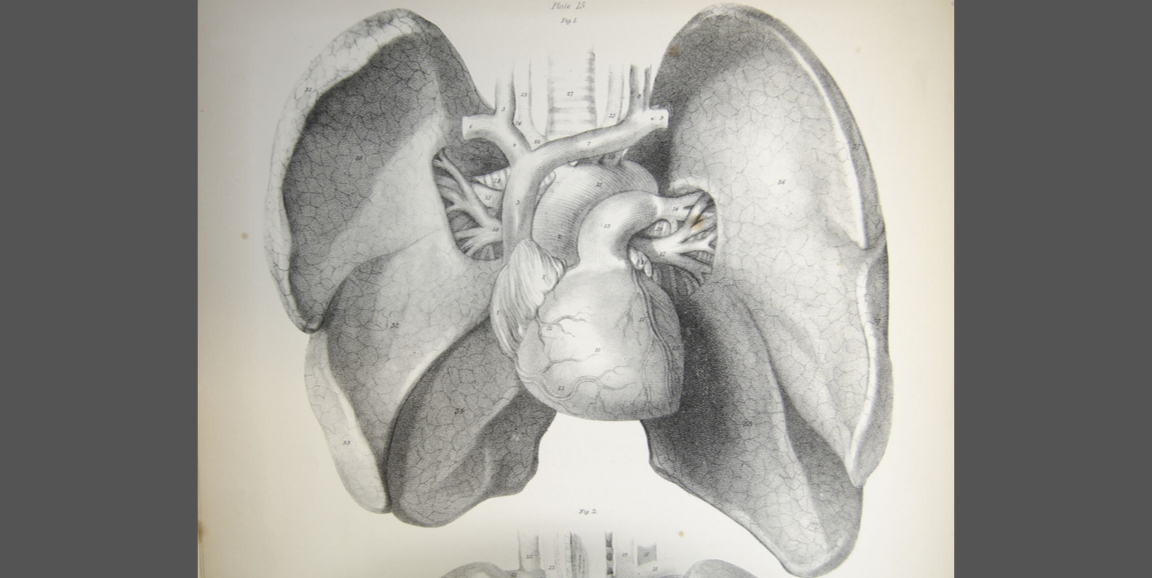

Lung transplants do not last as long as other solid-organ transplants, with only about half of recipients alive after five years. But a piece of research that evolved from the Nobel Prize discovery may help to change that.

Semenza's portion of the award recognized the discovery of HIF-1 alpha, a protein that switches genes on and off in response to low oxygen levels. This protein and its sister molecule, HIF-2 alpha, play important roles in maintaining the health of blood vessels. Loss of healthy blood vessels is a big contributor to failure of lung transplants.

Starting in 2011, Nicolls, a pulmonologist, and his Stanford team began publishing research with Semenza in which they increased HIF-1 alpha and HIF-2 alpha levels in animal models of lung transplant. When these proteins were more plentiful, the transplanted organs were healthier and lasted longer.

From that work, they've devised and patented a medication to turn up HIF-1 alpha levels. "It's a fluid that surgeons will apply to the transplanted lungs at the time of the operation to enhance natural blood vessel repair," Nicolls said. The treatment is in the process of being brought to market.

Nicolls and Semenza are figuring out how to apply the same principles to chronic lung transplant rejection.

"Lung transplant rejection is like a heart attack of the airways: You lose blood supply and get a scar, which turns into chronic rejection," Nicolls said, adding that chronic rejection is the No. 1 killer of lung transplant recipients. But turning up the HIF proteins can slow or reverse the process.

Semenza has been an important mentor and collaborator, Nicolls said, adding "He's a very generous but very careful and rigorous scientist."

And their findings illustrate the value of basic science, driven by curiosity rather than a particular goal. When Semenza first discovered HIF-1 alpha, he could not have guessed that the work might someday lead to longer-lasting lung transplants.

"When you learn how cells operate, the lessons can have very broad implications that only become apparent as years and decades go by," Nicolls said.

Image courtesy of the University of Liverpool