It's not really news that elderly people with a significant smoking history are at increased risk for lung cancers. Annual, low-dose computed tomography scans for those at especially high risk have been shown to be a useful way to catch the disease early enough to reduce deaths. But this type of screening has a high false-discovery rate, and only about 5% of eligible patients actually choose or have access to regular CT scans.

Radiation oncologist Maximilian Diehn, MD, PhD, and hematologist and oncologist Ash Alizadeh, MD, PhD, and their colleagues are working on another option: a blood test that could identify people with early-stage lung cancer by detecting the presence of tumor-specific mutations in the tiny bits of DNA that naturally circulate in the bloodstream. They published their findings recently in Nature.

As Diehn explained:

Non-small cell lung cancer is the number one cause of cancer deaths. One of the main reasons it is so deadly is that the majority of patients aren't diagnosed until they have metastatic disease, which is generally incurable. However, when patients are diagnosed when the disease is still localized to the chest, a large fraction can be cured. We reasoned that a blood test could help to increase the fraction of at-risk patients who are screened.

The blood test builds on a technique I've written about here before that was developed by Alizadeh and Diehn called CAPP-Seq. CAPP-seq, which tracks circulating, tumor-specific DNA, or ctDNA, has shown promise for its ability to identify how a type of lymphoma is responding to treatment -- i.e., is it going away or are more aggressive therapies likely to be needed? -- and to predict in which lung cancer patients the disease is likely to recur after seemingly successful treatment.

In the current study, Diehn and Alizadeh integrated information from CAPP-Seq with other molecular features of non-small cell lung cancers to develop a test they call 'lung cancer likelihood in plasma', or Lung-CLiP. After optimization, they found that Lung-CLiP could identify between 40% and 70% of patients with early-stage lung cancers.

Although the assay is currently less sensitive than a low-dose CT scan, it has a significantly lower false discovery rate. Therefore, the researchers envision a potential two-tier screening strategy in which a patient who is unable or unwilling to receive a CT scan could receive the Lung-CLiP test. Patients with positive Lung-CLiP results would then receive a CT scan to confirm the diagnosis. This hybrid approach could lead to the screening of many more high-risk patients than is possible with the CT scan alone, and potentially could dramatically increase the number of lives saved by such screening from the current estimate of about 600 per year to around 12,000 per year.

"This approach would be analogous to how stool-based testing is used to increase rates of screening for colorectal cancers, especially in populations where adoption of colonoscopy is lower than recommended," Alizadeh said.

In addition to developing a potential screening tool, the researchers learned some additional valuable information.

As Diehn explained:

Not only were we were able to determine that the majority of early-stage NSCLC patients do shed tumor DNA into the circulation, which suggested that developing a screening test would be feasible, but we also noted that the level of ctDNA in plasma before a patient begins treatment is strongly prognostic. That is, the majority of patients with relatively low ctDNA levels are cured by surgery, while most patients with high ctDNA levels ultimately experience a recurrence. This suggests that pre-treatment ctDNA could be useful for identifying patients who might benefit from more aggressive therapy.

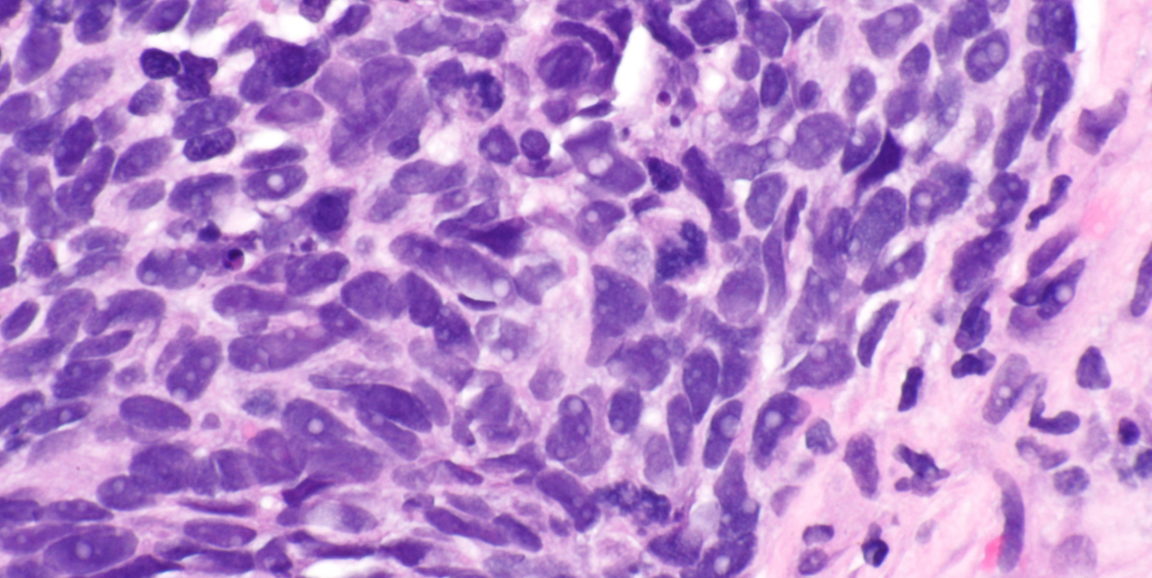

Image by Librepath