The first time I walked up to the Palo Alto home of the legendary scientist Ron Davis, PhD, it was with a heavy heart. It was early evening in the winter of 2016 and, in the fading daylight, strings of white lights hung across the wide green front lawn lit up. A hopeful sign I thought -- but I really just wanted to get back in my car and drive away.

Instead, I gripped a reporter's notepad in my right hand, and slowly crossed the porch to the stately front door. A handwritten note taped there said: "Please do not knock or ring bell before 3 p.m. Call or text. Very sick person." I paused, looked at my watch, thought of Ron Davis' sick son sequestered inside, and knocked softly.

Little did I know that I'd be returning to this house many times over the next four years in my obsession to understand how a mystery disease had left Davis' son, Whitney Dafoe, isolated for years in a back bedroom, unable to eat or speak.

My initial instinct to turn away from such tragedy slowly transformed into a desire to share this story of suffering and grief, of social injustice and of a deep belief in science.

And, at its core, it's even more than that. This is also a story of how a family's love for each other has brought hope to so many.

The result is a book, titled The Puzzle Solver: A Scientist's Desperate Quest to Cure the Illness that Stole his Son, that I wrote with Davis and was published in January. It follows Ron Davis as he tries to solve the confounding mystery of a little known, often dismissed disease, now called myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome or ME/CFS.

Searching for a cause and cure

But his journey doesn't end with the book. The search for a cure continues alongside the emergence of new concerns -- voiced by Davis, and now Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease -- that people who are sick for months after having COVID-19 could have ME/CFS.

Back on that 2016 winter evening, I'd been assigned to write an article for Stanford Medicine magazine about Davis, a professor of biochemistry.

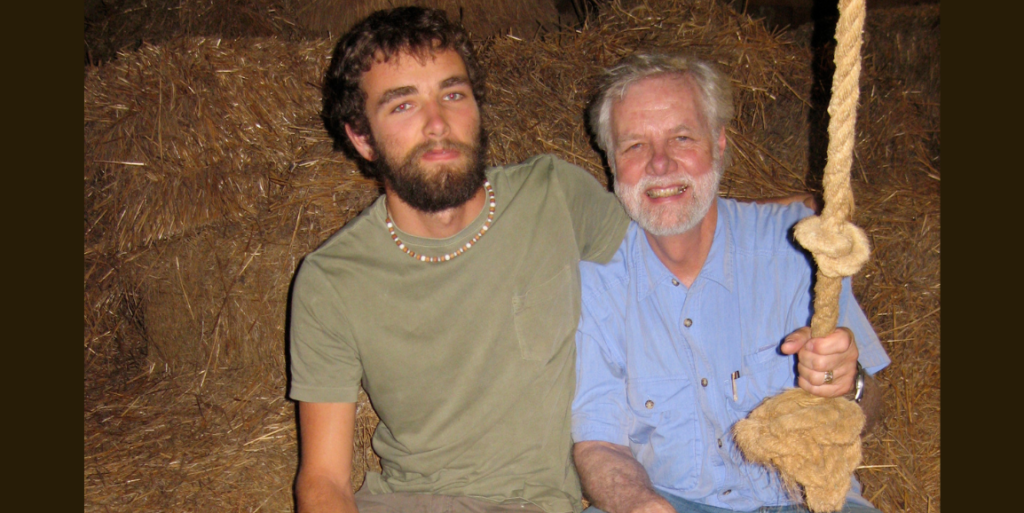

Davis had just announced that he was changing course, after decades of groundbreaking genetics research, to focus on finding a molecular cause and potential cure for the illness that had struck his son. Davis is joined in his quest by his wife, Janet Dafoe, and their daughter, Ashley Haugen, who are all committed to working together to do everything they can to find a cure for this disease.

Whitney Dafoe has one of the most severe cases of ME/CFS, a disease marked by multiple symptoms that include unrelenting, debilitating fatigue, brain fog and unrefreshing sleep. Scientists estimate that the disease affects 20 million people worldwide.

In my magazine article, also titled The Puzzle Solver, I wrote about Dafoe, how he traveled the world as a photographer, and was sick for years before he was finally diagnosed with CFS. But I hadn't been able to interview him. He was far too sick for that -- just sensing or hearing people could leave him completely depleted for days. Talking was impossible.

The article describes how Davis' research over the years had helped change attitudes within the scientific community. His scientific discoveries helped prove that ME/CFS is indeed a biological disease, and not a psychiatric disorder -- as many believed. His work also pointed to new possibilities for treatments and potential cures.

Understanding the disease

But my research had just begun: I needed to understand what had gone so horribly wrong that these sick people were disbelieved and mistreated for decades. Why wasn't there enough federal funding to research this widespread disease? Why were doctors sending patients to psychiatrists or psychologists? Why had family members believed that their loved ones were making up their debilitating symptoms?

I wanted to better understand the disease by talking with people sick with it. So I found them in support groups and rallies. I drove to Lake Tahoe to track down patients from a 1980s outbreak of the illness which people were calling a "mystery disease."

More than 30 years later, they are both still sick and hoping for a cure. After being mocked and disbelieved, they eventually fled the Tahoe area and have since managed to care for each in a new community.

It was two years before I was finally able to interview Dafoe. He was in a hospital bed, preparing for a procedure to replace the feeding tube inserted in his belly with a new one to keep him alive. He still couldn't eat or speak, but with a new medication and with great effort, he could communicate a bit using his hands and facial gestures.

I returned every two or three months to sit and "listen" to him communicate with his hands. I told him I would do my best to tell his story in a way that showed his personality. I'd write that he is funny and adventurous, and he sees beauty in small things. He is much more than a sick man, lying helpless in bed. He yearns to be off traveling the world.

And he wanted me to know how he feels about his father's determination to find a cure for him and other patients. On a soft brown blanket on his bed, using his finger for a pen, he spelled out the word "HERO." Then he smiled.

Tracie White is a science writer at Stanford Medicine and author of The Puzzle Solver: A Scientist's Desperate Quest for the a Cure to the Illness that Stole his Son.

Top photo by Ashley Haugen; Other photos courtesy of the Davis/Dafoe family